Ephemeral Architectures, oodles of Noodles, and anarchic magic: Thomas JW Wilson follows the circus caravan at the London International Mime Festival 2015

Returning for its 39th year, London International Mime Festival (LIMF) continues to be one of the UK’s strongest advocates for contemporary circus, programming well-established companies, such as the ever-popular Circus Ronaldo, and the ever-innovative Aurelien Bory of Compagnie 111, alongside the latest generation of emerging artists. This year has been no different, with a particularly strong showing for UK-based artists, the likes of pioneering Mime Festival regulars Gandini Juggling featuring alongside feted newcomers Barely Methodical Troupe with their Total Theatre Award winning work Bromance; Joli Vyann, presenting their latest dance-circus hybrid, Stateless; and Knights of the Invisible’s Black Regent, featuring Scottish contortionist Iona Kewney.

LIMF has also come to serve as something of a barometer of the health and direction of contemporary circus. A careful glance at the programme notes highlights the extent of pan-European collaboration that facilitates the wide range of current circus work. Paris-based Thomas Monckton is a prime example of this collaboration, his piece The Pianist supported by the powerhouse of Finnish circus Circus Aereo – a company who are adept at collaborating with circus artists of various disciplines. This is borne out by the fact that Maksim Komaro, Circus Aereo’s artistic director, also has a hand in another Mime Festival show, No Fit State’s Noodles.

Founded in 1985, No Fit State are one of the longest-running UK contemporary circus companies. Retaining the spirit of the classical circus, ‘travelling in trucks, trailers and caravans’, they have built up an impressive history of striking and subversive performances. Their latest offering, Noodles, ‘facilitated’ by Holly Stoppit, is something of a departure for the company as they put, in their words, ‘a circus into a theatre’. In other words, they are not in their own familiar tent, but presenting in built theatre venues.

At the heart of this vibrant indoor work, as the name suggests, are an increasing array of giant ‘noodles’ made from rope of differing lengths and diameters. The five-strong cast proceed to manipulate and climb these noodles, as well as often finding themselves at the mercy of particularly disobedient groups of noodles. Noodles is essentially a fusion of object play and classical circus disciplines, including cloud swing, tight rope, hand-balancing, clown characters and magic, amongst others.

The most engaging sections of Noodles are those which emerge out of the magic tricks or Ilona Jäntti’s aerial choreography – particularly a robust and well-paced aerial quartet, set on five overlapping cloud swings at the back of the stage. The close-proximity magic is ably executed by Miguel Munoz Segura and has some genuine surprises.

All five performers work the crowd hard, but the scale and pitch of the broad clown characterisations doesn’t quite fit the intimacy that a theatre space like Jacksons Lane creates. Playing at this scale, these clowns need more vulnerability and a little more subtlety. Noodles might also well benefit from a younger audience than the night I saw it, as well as a tighter running time.

Magic, or rather misdirection, is also a central feature of newcomer Oktobre’s eponymous first show. Set in a darkly surreal world, Oktobre sees a series of striking and inventive vignettes that, when played together, construct their own dislocated logic. These vignettes are often populated by disobedient objects: a red balloon that moves of its own accord; small red balls that appear and disappear, to the frustration of a seated figure; and an acro-balancer unable to control his own body, leading to a growing sense of an unstable and shifting world. All of this anarchy is absolutely precisely executed by the four prodigiously skilled performers, their physical plasticity allied with the meticulously controlled staging, contributing to an unstable and shifting world.

Eva Ordonez Benedetto’s static trapeze sequence creates a marvellously tantalising and palpable sense of danger. Composed of a series of slow and purposeful movements Ordonez Benedetto conjures a sense of her painful obedience to an unseen force. This hinges on her apparent ability to defy the rules of gravity, particularly in the moment when she moves from hanging from the bar by her knees to hanging from the backs of her ankles, slowly and meticulously sliding down the backs of her calves. It is astonishing moments like these that appear throughout Oktobre, moments in which technique is artfully married to dramaturgy.

Another richly rewarding element of Oktobre, which was less present in Noodles, is the harmony the performers achieve with each other, fusing their varied disciplines through deftly pitched personas. Eva Ordonez Benedetto’s austerely commanding presence is a well-judged foil to the confused, and harassed Yann Frisch, whilst Jonathan Frau flips and capers with an urgent sense of foreboding.

At points Oktobre plays with Marx’s oft-quoted observation that history repeats itself ‘the first as tragedy, the second as farce’, with the company replaying earlier images and sequences several times, each subsequent time further distorted and comic. These comic elements though retain the dark and foreboding ambience the company have crafted. This results in Oktobre‘s genuinely surprising and captivating quality, reinforced by the performers ability to shift easily between brooding poise and anarchic activity.

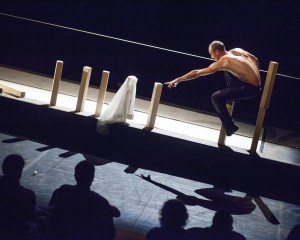

Sharing the technical precision of Oktobre, but staging a markedly different kind of work, is another of the UK’s longest standing, most prolific and innovative circus companies, Gandini Juggling. 4 x 4: Ephemeral Architectures is the newest of Gandini Juggling’s creations and sees them exploring the possibilities to be had in blending ballet and circus. With 4 ballet dancers and 4 jugglers, backed by a string quintet from Camerata Alma Viva, 4 x 4: Ephemeral Architectures crafts a dizzyingly interplay between thrown objects, dancing bodies and the shifting rhythms of Nimrod Borenstein’s score. Working in partnership with choreographer and ex-Royal Ballet dancer Ludovic Ondiviela, Gandini Juggling return to many of the concerns of their early work – a rigorously technical deconstruction of dance and juggling, fusing this with Sean Gandini’s precise and adventurous mathematically-driven patterns. This time, though, their interest is not in the creation of a hybrid vocabulary, part-juggling, part-dance, but rather an exploration of two vocabularies; Ondiviela’s choreography retaining a clear degree of separation from Gandini’s patterns. Thus the dancers carve punching and arcing positions in space in response to the juggling patterns, or gracefully and stridently spring through the pathways of the flying objects.

In crafting the juggling patterns, Sean Gandini has drawn on several of the motifs that Gandini Juggling have created over the course of the last two decades. Utilising, in turn, the three classic juggling props (balls, rings, clubs), the patterns are, in effect, offers to the dancers to respond. An arcing four-person, multi-ring, passing pattern creates three ‘archways’ parallel to the audience. Behind these archways the dancers move in short bursts to strike poses that echo the trajectory of the airborne rings. This visual harmony is one of the chief pleasures of 4 x 4: Ephemeral Architectures.

The invitation for one artform to respond to the other is at the heart of the work, and is most explicitly stated in juggler Owen Reynolds’ question to the audience: ‘Is it possible to dance whilst the ball in the air’, to which the sylph-like dancer Kate Bryne answers with fragments of popular dance as Reynolds tosses one ball high into the air. The air of humour this generates is a vital part of Gandini Juggling’s work, and arises and recedes throughout 4 x 4: Ephemeral Architectures – tempering the more austere and complex moments.

There is, though, an increasingly darker side to Gandini Juggling’s work, and in 4 x 4: Ephemeral Architectures this emerges in a driving, impassioned and arresting duet between anarchic juggler Sakari Männistö and dancer Erin O’Toole, whose steely calmness works to gradually reel Männistö in before ‘clipping his wings’. This moment is one of a number of small flashes of images of narrative that Ondiviela inserts into the work – like the humour ensuring that 4 x 4: Ephemeral Architectures is not just an experiment in form.

Despite Gandini Juggling’s initial intention to keep the two vocabularies distinct, there are still moments where the dancers juggle and the jugglers dance – their roles blurring. This is exemplified in the section titled ‘Yellow Yellow’ where a 20-move, three-ball juggling sequence is divided amongst the seven other members of the company, grouped together centre stage and each one throwing one ball. At the same time, using three different coloured balls, Kati Ylä-Hokkala juggles the same pattern in its entirety downstage left. As the septet throw their individual balls (or not) they variously call the colours of the balls that Ylä-Hokkala throws. This mathematically complex and visually striking motif gradually expands as the septet add lunges, lifts and jumps to their score, creating a living and breathing architecture that swells beyond the physical space it occupies. This architecture though is not just a visual and spatial one, but also has its own rhythmic musicality – a musicality that gives juggling, like dance, its life.

It is the moments of overlap between dance and juggling that Gandini Juggling’s thesis that the two artforms share the same core principles is most evident. Gandini’s assertion, that this can be seen even in the most prosaic of facts that both sets of artists must ‘count’ the beats of their performance with a ferocious precision, only hints at the very beginnings of the richness of this collaboration.

A different form of cross-discipline collaboration is the basis of Lonely Circus’s Fall, Fell, Fallen. This slow-moving and atmospheric work sees acro-balancer Sébastien Le Guen’s precise, shifting poses set in dialogue with Jérôme Hoffman’s electro-acoustic soundscapes. Where Gandini Juggling’s dialogue is richly nuanced, Hoffman and Le Geun’s is rather more concentrated.

Fall, Fell, Fallen is a series of short vignettes – interrupted, driven and shaped by Hoffman’s electronic compositions. These vignettes are slickly composed, and visually striking, but they lack a clear sense of development and it is never quite clear what their payoff is. Although at times Le Guen falls, impressively so too, the implications of these moments aren’t clear. There are moments, though, where the sound and action become greater than the sum of the parts. First is a playful tense sequence in which Le Guen ‘plays’ a tight rope rigged to an amplifier. As Le Guen strikes and slides his feet across the rope, it feels like he is ‘jamming’ with Hoffman, who darts around his amplifiers, striking at different buttons and twiddling different knobs. This moment of heightened animation is unforced: Le Guen teetering and darting back and forth across his rope – agile, poised and risking missing the beat.

The second moment where Fall, Fell, Fallen transcends the two disciplines is close to the end of the show. With one end of a plank of wood resting on the floor, and one attached by a cable to the ceiling, Le Guen, ‘surfs’ the inclined plank – the plank pivoting and swinging in response to the pressure of Le Guen’s feet. In this moment, Le Guen’s stately quality makes perfect sense and Fall, Fell, Fallen finds a poetic register: Le Guen alone with and against the physics of his art.

It is these moments, when technique and dramaturgy combine, that circus is transported into something greater than the sum of its parts, making us aware of the power of the form. And as the supporter of so much groundbreaking work, LIMF has established itself as the natural home for contemporary circus, in all its diversity.

That contemporary circus continues to embrace such an astonishing array of performance practices and collaborations, as witnessed at the London International Mime Festival 2015, also marks out the form’s rude health.

Thomas JM Wilson saw the following shows at the London International Mime Festival 2015:

No Fit State Circus: Noodles, Jacksons Lane

Oktobre, Purcell Room, Southbank Centre

Gandini Juggling’s 4×4: Ephemeral Architectures, Linbury Studio, ROH

Lonely Circus: Fall, Fell, Fallen, Purcell Room, Southbank Centre.

Featured image (top of page): Gandini Juggling’s 4×4: Ephemeral Architectures. Photo Beinn Muir.

Spring 2015 will see the release of Thomas JM Wilson’s book on the history of Gandini Juggling company.