In the first scene of Ciphers a nervous but determined Justine interviews for a job as an intelligence officer. Her interviewer, Sunita, is calm with a touch of dismissive. A large white paper screen passes across the stage in front of the pair, who are seated side-on to the audience across a white table. When it has passed, Sunita is standing up, interrupted, and Justine is wearing a leather jacket and handbag that she didn’t have on a second ago. She’s agitated and as soon as she starts speaking it’s clear that this scene doesn’t follow on from the last. She’s demanding and starts smoking, and though Sunita wants to get rid of her, something holds her back. Something has happened. Justine is dead, and this is her sister Kerry.

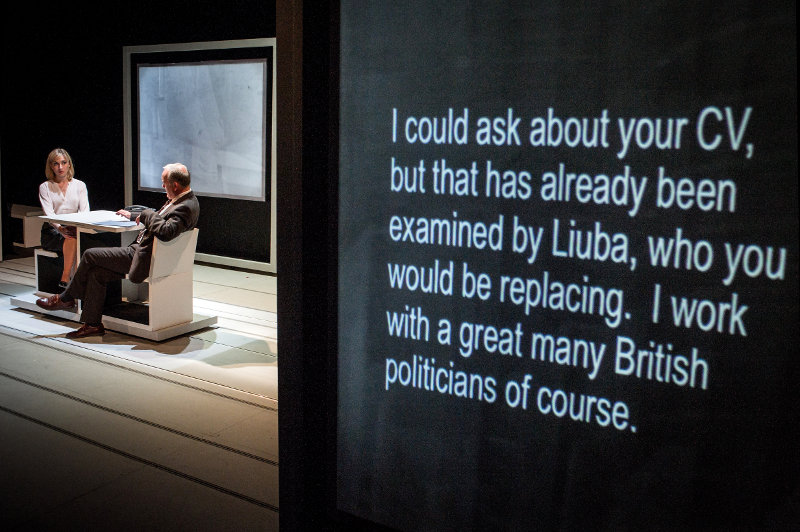

In the next scene, Justine is at another job interview, across the same white table, but this time she calls herself Julya, and the interviewer is a whimsical, confident middle-aged man. They speak Russian for some of the interview, and Justine says she grew up in Russia. Translations are projected onto screens at the sides of the stage – in the next scene they become works of art hanging in a gallery where Justine meets an artist, Kai, and his wife, Anoushka, who is played by the same actress, in the same clothes, as Sunita.

Ciphers switches rhythmically from scene to scene, not missing a beat, back and forth through time, adding layers to a suspenseful, tantalising mystery that makes its audience work hard. Throughout, we are required to decipher not only what is going on, but who we are watching, when, and how that relates to what we already know. Sometimes, as in the Julya story, we are not hearing the truth, and this makes it more complicated. We are completely drawn into this web, an active part of a story in which characters blur into one another and time becomes confused. At one point the artist Kai goes to bed with a desperate Justine, and in the middle of the night, grieving Kerry wakes up from the bed, slick with paranoia, leaving Kai asleep alone.

It’s clinically staged, and as precise and smart as a modern TV spy-thriller, though in an after-show discussion director Blanche McIntyre says they had particularly tried to avoid that. There are differences; Ciphers is minimalist, where TV and film revel in the use of technological clutter and large casts to make a work impressive. Here we rarely see more than two people onstage, and the only props are drinking glasses and, once, a small, outdated TV set. The paper screens and table and chairs are expertly moved around the stage – you rarely notice the joins in this high quality production.

Ciphers’ characters are trope-like and deliberately similar to one another, as if it didn’t necessarily matter who was who, at the end of the day. Perhaps it doesn’t, one feels – they are only actors after all. Justine and Kerry regularly analyse their relationship to each other and the ways in which they differ. Kai the artist and a Muslim youth worker, Kareem, are each manipulated by a forceful woman who has something on them. The females are generally dominant, and even when patriarchal Russian boss Koplov seems to get his way by bedding Justine, he has been tricked into thinking she is someone else.

The storyline too, when ironed out and considered, is rather clichéd. The only spy case that we see into that’s separate from Justine’s rise and demise looks at the intimidation of youth worker Kareem, who is forced to spy on a ‘suspected terrorist’ in his community. Justine is not yet trained to properly handle the situation and the youth worker goes missing, suspected dead. Plotlines collide, and in the end the events leading up to and causing Justine’s death are banal to the point of dismissal by her bosses, Sunita and Koplov the Russian. All this adds to the clinical, minimal feeling – we don’t much get a feel for Justine’s anguish and the pressure she’s under, and actually it’s hard to care. What is important to playwright Dawn King is the feeling that the characters are pawns in a system and that their individuality is limited by the society they are part of. What’s impressive is how much we, as an audience, enjoy being made to feel this, and how the show’s almost flawless structure and beautifully clean design and direction are more than enough to keep us enthralled.