By their own admission LIFT have wanted to programme She She Pop for the last few years, only succeeding in doing so this year, and given the evidence of She She Pop’s latest piece Testament it is not hard to see why. A female performance collective, though featuring male members, She She Pop explore the social boundaries of communication though working with autobiographical material and canonical texts framed by a task-based approach to performance. This 2010 show is contemporary theatre-making at its most adept, blending many of the tropes of postmodern theatre into a seamlessly swift two hours of poignant reflection on the relationship between fathers and their offspring.

By their own admission LIFT have wanted to programme She She Pop for the last few years, only succeeding in doing so this year, and given the evidence of She She Pop’s latest piece Testament it is not hard to see why. A female performance collective, though featuring male members, She She Pop explore the social boundaries of communication though working with autobiographical material and canonical texts framed by a task-based approach to performance. This 2010 show is contemporary theatre-making at its most adept, blending many of the tropes of postmodern theatre into a seamlessly swift two hours of poignant reflection on the relationship between fathers and their offspring.

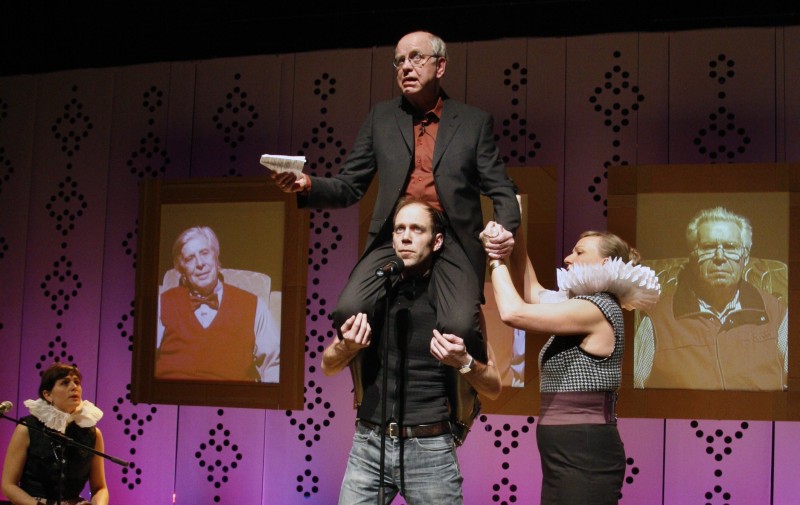

To achieve this four of the performers from She She Pop are joined by three of their own fathers, leading this septet to attempt to negotiate not only the form and content of the show, but also the nature of their relationships with each other. The fathers appear not to be easy working partners, and She She Pop treat us to re-enactments of rehearsal discussions. Speaking from recordings of their rehearsals played through headphones the company deliver the fallouts and objections to their art with a cool detachment – as if honouring the fractious process and the difference in attitudes of the generations: ‘This is too exposing’ one father protests: nudity he can cope with, but not the exposure of his personal life. But She She Pop continue, searching for both the questions and answers to one of our generation’s looming challenges – how to care for our ageing population.

At the core of these intergenerational struggles the company situate Shakespeare’s King Lear, deconstructing this text throughout the course of piece. They plunder the trajectory of Lear’s relationship with his daughters to structure the work, sparking discussions about a child’s duty of care to their father and the father’s duty to provide for their child. Thus, at intervals, the children and their fathers stiffly recite Lear’s and his daughters’ statements of love and, later, dissatisfaction; only to then unpick the thrust of the characters’ counter-arguments with contemporary examples. Lear’s demand that Goneril and Regan host his 100 knights for instance, is morphed into more suburban concerns: how might a daughter house her father’s extensive library of books when he becomes too frail to look after himself and moves in. In these transformations She She Pop render the monumental mundane and grand tragedy, bleakly comic.

At the heart of Testament, and the starting point for the unpicking of family strife, is the disposal of parental wealth and affection. This is most explicitly set out in a delightfully rational reckoning of the direct relation between the bestowal of financial and emotional inheritance on the child and the degree of affection this generates. Accompanied by a hand drawn graph of the correlation between the two, one of the fathers pragmatically exposes the unspoken conflict between the desire to be both free from our parents/children whilst still demanding their affection and care. Does he bestow all his wealth now for a temporary upsurge in affection, hold on to it all until the bitter end, or distribute it slowly through his dying days? He proposes the latter… if only he can predict the date of his death.

Strikingly poignant is the testimony of the fathers, the moments of resistance to their children’s accusations, imagined futures of their own demise and troubled reflections on the way their children live their lives. In these moments She She Pop craft a counter-narrative to the Lear story that allows us to ally with both sides of the generational divide, hinting at our own fears and concerns. Although the company’s reading of Lear accuses Lear of monumental foolishness born out of fear, Testament suggests not only a foolishness on both sides, but also charts the rawness and reality of the worries of youth and age.