On 27 October I sat in the auditorium at the Brooklyn Academy of Music, New York and witnessed a production of Uttar Priyadarshi (literally meaning ‘the later life of Ashoka'), presented by Ratan Thiyam's Chorus Repertory Theatre from Manipur, India. It was not, however, the 'active witnessing’ that sociologist Paul Gilroy attributes to the ideal experience of a spectator at a work of live art, but rather an observational procedure.

Uttar Priyadarshi has little plot in order for the audience to focus less on story and more on the conflict of good and evil that director Ratan Thiyam believes exists within all of us. For Thiyam, this resolution of internal conflict is more important than that which exists without, such as the manifest conflicts in his home kingdom of Manipur, for instance. Manipur is an extraordinarily culturally rich kingdom with unique cultural forms, including one of the five principal classical dance-drama forms on the subcontinent, and an indigenous martial art, Thang Tha. Manipur is, however, also a realm plagued by violence and internal strife. An independent kingdom until it was incorporated into the British Empire in the 1890s. Manipur gained independence alongside India in 1947, but was forcibly incorporated into the Indian state two years later. Since then there has been a move toward independence and the Indian army has for some time been stationed in the state. Manipur's population consists of numerous tribes, some of whom are also in conflict with each other.

Ratan Thiyam decries violence on all sides as simply self-serving. His message – triumphing both by non-violence and the search for the resolution of conflict within – is a noble one.

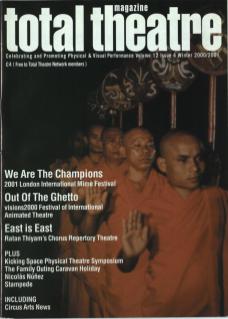

The production I saw, Uttar Priyadarshi, is based around the story of the Indian Emperor Ashoka, who lived more than two thousand years ago. Ashoka, through barbarous battle, was able to conquer and unite most of the subcontinent. However, the concomitant murder and bloodletting ultimately appalled him. Buddhist philosophy, with its maxim of finding eternal truth within, influenced him. Ratan Thiyam is not a Buddhist, but uses this story in his play to reach an audience beyond Manipur and to address conflict that is not particular to Manipuris but to us all. Buddhism is arguably the most espoused and lauded Eastern philosophy in the West. The play begins with a long Buddhist incantation by a group of actors dressed as Buddhist monks. It ends with words boldly displayed in English surtities above the stage, telling the audience that human suffering is not without but within and the conflict that must be fought and won by each of us is the interior battle: 'Only through compassion can you conquer evil.'

These heartfelt and worthy statements are poignant, particularly in the context of the political situation in Manipur. However, the work rarely goes beyond the didactic. Good and evil are presented as a collage of singular tableaux rather than as interacting eternal and dramatic conflict. At no point does the play get below the skin. At no stage is it engaging on a deeper level, disturbing our unconscious to enable the spectator to reach a more profound consciousness. There is no catharsis. If we are then to view it on an intellectual level only – in the absence of sophisticated Brechtian dramatic strategies – a pamphlet would have done the job more cheaply and effortlessly.

This is, perhaps, inevitable on a Western stage (wherever it is topographically located). Despite the theories and practical experiments of innovators such as Adolphe Appia in the early twentieth century, the nature of the spectator/spectacle relationship remains largely undisturbed in the early part of the twenty-first century. The Western stage is primarily one that provokes a mindset of observation rather than participation. There are some rare exceptions, but Uttar Priyadarshi is not one of them. Ratan Thiyam, like many non-Western practitioners over the last fifty years, has rejected contemporary Western theatre as a model and searched in his roots for new forms. Yet his work – both in the East and the West – is so often performed in theatre buildings that are legacies of the nineteenth century. This production sits easily in such a framework. The inherent weakness of the spectator/spectacle relationship when performed in conventional theatres, such as the Brooklyn Academy of Music, is further deepened by the inability of Uttar Priyadarshi to disturb; to get below the spectator's reason and confront her or his deeper strife. Consequently, as one is unable to engage dynamically with Thiyam's edict, the production veers too close for comfort toward exotification.

There is a conundrum faced by any non-Western critic analysing non-Western performance taking place in the West for a predominantly Western readership. Because there are relatively few productions presented in the West of non-Western forms, the spectator is relatively uninformed and each work becomes representative of the whole opus for its Western spectator. An anxiety emerges for the critic: if I criticise the work as rigorously as any other, then given that this work is by the most renowned director in South Asia – promoted as having similar status to Brook, Suzuki, Barba and Mnouchkine – will this consciously or unconsciously provoke a rejective response to all South Asian work? Quite possibly. Of course, the only option is to publish and be damned.

However, in the context of a critical reading of non-Western performance, it is crucial for the spectator and reader to therefore remind her/himself that what she/he may be seeing/reading is only one piece of work by one director, and although this particular production may have failed, it is only one of a number of experiments and, consequently, this process of experimentation in totality must not be rejected. Furthermore, it is important for the spectator and reader to remind herself/himself that international work is presented in their countries usually only through support by its government; a government more inclined to support work which presents its country in the best light than work which is aesthetically, artistically and politically cutting edge. The work, therefore, is inherently conservative.

It is furthermore important to look at the process of selection in the UK. The people who select work for our international festivals are, despite the growing cultural diversity of the UK populace, comprised of those who represent the dominant global ideology. Non-Western work in this context is inevitably exotified. Experimental, non-conforming work is subjected to this pernicious filtering process. The work is as commodified (with less money) as a Prada handbag. Why is it that if you walk into Selfridges, you will find it difficult to find a dress made by an Indian fashion designer? Do you think that only people from certain countries have a creative sense in this form? No, it is all about marketing and who controls the means of distribution.

So how do we find a means of experiencing non-Western art without looking through the tinted glasses of Western producers and the blinkered vision of conformist cultural commissars of non-Western governments? One option, it seems, for those interested in seeing challenging, experimental work that comes out of the Third World, is to put aside, at least temporarily, the homespun international festivals, and spend some of their hard-earned cash to become 'cultural tourists' for a few weeks. The opportunity would then be there to see work in its social and political context and to discover first-hand the roots from which the practice springs.

Another option is to create new fora for artistic dialogue. And we can still dream. Perhaps, in this context, art on the Internet still offers one of the few relatively direct worldwide meeting grounds for artists and witnesses. Of course in many underdeveloped countries there are financial and technical obstacles to such encounters and access is still limited. However, it may only be a matter of time before such obstacles are history.

Ajaykumar is an artist and lecturer in multidisciplinary art at Goldsmith's College, University of London.