Mime and circus are increasingly vying for the same performance space. Festivals of mime, street performance and circus have often worked side-by-side in the marketplace and on street corners. Nowadays, they are just as likely to be seen together on the same physical theatre stage.

Both new mime and new circus have perversely come of age in the cultural wasteland of Thatcher's Britain – independently minded products of a cynical enterprise culture that never favoured the minority arts. Now they are becoming increasingly integrated as both seek new audiences and a wider scope for their performance skills.

While mime has begun to embrace a greater variety of physical skills and performance mediums to reach a wider audience – transcending mainstream perceptions of it as elitist and obscure – circus is demanding to be taken seriously as a performance art form after years in the cultural backwater of traditional family entertainment.

Now that the animals are gone from most of British circus the accent has been thrown onto human physical skills and dramatic expression. Like the new mime, circus is looking for greater depth, character, plot and theme development in its performance as well as trying to make the old skills work in new ways. The new emphasis on complete theatrical performance has created a need to develop character and plot on the stage or in the ring, usually by means of the circus skills as dramatic or emotional metaphors.

This has seen circus go back to its roots, in many cases reviving the techniques and characters of Commedia del Arte or drawing on the influence and principals, not the practices, of theatre, dance and mime.

The scope of new circus has widened and can be seen in everything from the radical avant-garde dance and theatre of Ra-Ra Zoo and The Circus Space to the more folksy ring theatricals of Circus Burlesque and Snapdragon, or popular overseas acts like Cirque du Soleil and Archaos (who are more intent on updating the traditional circus with new tricks but basically keeping the tried and trusted Big Top format).

What new circus has invariably retained is what could be described as the essence of circus performance – variety and excitement, along with its ability to relate to a popular audience. However, that variety is now no longer restricted to the usual circus skills – tightwire, trapeze, juggling, clowning – but also embraces dance and mime, theatre and puppetry.

Both circus and mime have crept into the popular cultural consciousness – particularly since the 1970s. The high profile of artistes like Marcel Marceau and Lindsay Kemp and pop stars like David Bowie and Kate Bush has brought the theories and practice of mime to a new audience. Circus was similarly assimilated into youth culture particularly in the psychedelic era when the wild and wonderful image of circus was revered by the hippy sensibility. The fashionable taste for the surreal, existential and absurd in particular drew on mime and circus for its inspiration and imagery.

The psychedelic / New Age attitudes and fashion trends of the 1990s have extended and built on this mutually beneficial relationship, making physical theatre increasingly popular to many who would not have thought twice about going to the theatre before. It is from this status as an accepted – albeit still minority – form, that both mime and circus are launching into new areas that cross over under the physical theatre umbrella.

The kinds of hybrids that are emerging now are a reflection of a postmodern world where everything is up for grabs and all things there to be used in the perennial search to refine and review ways to say what can be said physically. The mime, mask and circus theatricals of Mummer & Dada, the avant-garde dance and physical theatre of DV8 and Momix are just some examples of the possibilities of this kind of integrated performance.

One area of performance which mime and circus have always shared is that of the clown or fool. The school of Jacques Lecoq and subsequently Philippe Gaulier has established clown in mime as a whole way of being in itself.

The character of the clown in circus is pivotal and in new circus is being further explored as an entity in itself by acts like NoFit State, Jon Leigh, Skin & Blister, or Albert the Idiot, while The Moving Picture Mime Show and Theatre de Complicite display their clown inheritance. Nola Rae and The Right Size are new mime that draw on clown for comic theatre.

Clowning is the natural and historical bridge between mime and circus – with its use of visual gags and physical skills on the small stage, requiring close eye contact with the audience if not actual participation and its potential to develop character and convey feeling.

Both new circus and new mime have been criticised for a lack of emotional and dramatic depth – illusion for illusion's sake. Having depended on the visual they have not developed the medium of the other senses. With both looking to expand their artistic scope and to reach new audiences they have much to offer each other now.

Both mime and circus skills involve tightly choreographed movements with every action set and worked on. Circus has the explosive, exciting dynamics and dangerous physical skills that require strength, discipline and hard training to master. The learning advances are quick and the performance impact immediate.

Mime is a more poetic physical medium that communicates with depth and subtlety, imagination and precision. It takes longer to master and goes for more profound effect. It can give detail to the large brushstrokes and wide open spaces of circus territory, while circus can provide an exciting dynamic that mime has often lacked in the past. Mime can direct the eye with more precision to the subtle things that circus can say. Circus can bring those skills to a wider audience.

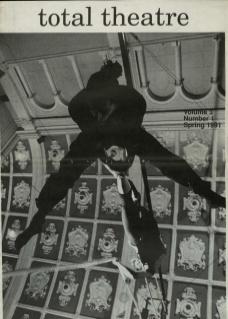

Circus inhabits the performance space that others cannot reach, 5-10 metres or more in the air on a trapeze, highwire and rope. It is another dimension for the essentially ground-based medium of mime to explore.

The best thing now is that the boundaries are gone and everything is wide open, providing fertile creative ground for new forms of physical expression. Circus arts training centres such as Fool Time in Bristol or the Circus Space in North London make no bones about their intentions in offering integrated as well as specialist classes in all the physical skills.

While there is undoubtedly dissent within both camps as to where both mime and circus are going, now should be the time for an embracing of all the possibilities rather than a throwing up of new divisions.