Performers in the early Twentieth Century used animal imagery and intercultural dramatic knowledge as a basis of study. For example: Mary Wigman, Hilda Holger, and later Bejart in Europe, and Martha Graham, and dancer and mime, Charles Wiedman, in the United States. Serge Lifar, a star choreographer of the Paris Opera and an ex-dancer with Diaglilev's Ballet Russes linked dance and mime in a collaborative sense by exclaiming: ‘emotion is the key for him [the mime]. His technique knows of no form, since it resides in the innermost recesses.’

Rudolph Laban claimed that the human carriage only became fully utilised in the Twentieth Century because of the innovations of modern dance and the acting techniques of Mime.

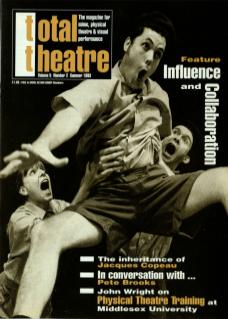

In the 1980s modern dance and mime based theatre has become part of a bigger theatrical movement – ‘physical theatre’.

In Dance, this lineage goes back further than we think and probably also draws on many now forgotten collaborations.

Martha Graham initiated theatre not just in her now familiar dance style and technique but in her collaborations with Isamo Noguchi (scenographer) and Jean Rosenthal (lighting design) which gave an integrity and status to what were then subordinate roles in the theatre. She once described Jean Rosenthal's lighting as being in line with her composition’s raison d'etre... ‘its inner pulse’. This pulse referred to the contorted torso contractions and spirals so evident in Graham's dramatic movement technique, which she evolved from observed styles of ‘emotional catharsis’, for instance in wailing and grief.

Rosenthal (who came herself from a Vaudevillian background) went on to train top American lighting designer Jennifer Tipton, who worked with Twyla Tharp, American Ballet Theatre and New York City Ballet.

It is generally accepted that from Graham's emotional pogrom came Merce Cunnigham and Erick Hawkins, both originators of their own dance techniques and the first men in her company during the 1940s.

The BBC's recent dance programme Dancing described Cunningham as being ‘trained’ by Graham. This is inaccurate as both men were trained ballet dancers, touring George Balanchine's Ballet Caraven in the USA in the 1930s. Both men utilised balletic qualities of movement and spirals in their respective techniques but these are also anatomically similar to the vertical utilisation of epaulment and aplombe found in the Russian Vaganova Academy which influenced Balanchine. Agrippina Vaganova herself rebelled against the encumbered training of classical dancers in the early Twentieth Century, especially the sexist stereotypic expectation of women to be ‘coquettish’ or to ‘flirt’ with their audience.

Cunningham's collaborations included avant-garde artists like Jasper Johns, and Robert Rauchenberg and the musical genius, John Cage. He explored all theatrical entities as separate, to be utilised and subordinated in any order of the theatrical mosaic.

In the late 1970s and early 1980s, the exploration of possibilities of modern dance resulted in ‘New Dance’. This explored feeling, emotion, and a new political awareness and concerned itself with the scenic environment of the body (Graham was concerned with the inner landscape).

It could be argued that Cunningham's work should now be described as ballet. And that the raison d'etre of London Contemporary Dance Theatre, founded in the 60s to promote the style of Martha Graham, is to be a repertory company celebrating a particular style and dance technique (as with the Royal Ballet). Contemporary dance, with the influence of New Dance and the explosion of groups like DV8, AMP and The Cholmondeleys now needs to be redefined.

The lineage of explorations in modern dance in the Twentieth Century have paralleled and often crossed the great innovations in Mime.

Latterly, collaborations and changes have created a hybrid genre called Physical Theatre, which in its many forms can be seen to have innumerable influences, which also include Japanese Theatre and New Circus.

For performers today there is a much greater and broader opportunity for developing corporeal movement performance. Practitioners skilled in the many aspects of physical, movement, and other performance work are willing and ready to come together in collaboration to explore possibilities and create new vocabularies.