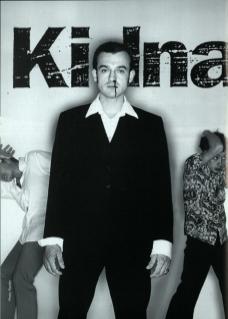

Have you ever fantasised about being the victim of a violent crime? The vast majority of us are glad to live in a country where such a threat is still remote. But if you prefer to live your life a little more dangerously, Blast Theory are currently offering two lucky individuals a once in a lifetime opportunity to be kidnapped.

You might already have seen their cinema advert. A dispassionate voice asks ‘have you ever wanted to leave everything behind for a few days?’, before announcing an 0800 number to telephone for further information. It's a small wonder that anyone calls, particularly as the advert ends with the chilling warning: ‘This is not a game, this is not a joke.’

If you're a serious thrill seeker, no doubt you'll think of calling. Next, you will discover that to be kidnapped all you have to do is pay £10 and fill out a registration form. This will provide your kidnappers with crucial information about where you live, where you work, what type of car you drive, and so on. Once you've joined the hit list, Blast Theory will take control. They will select ten applicants at random to place under surveillance. If you're one of the lucky ones, you'll know you're being watched when an envelope containing photos of you comes through your door. Out of the ten applicants under surveillance, only two will be selected at random to be kidnapped. You'll only know you've reached the top of the hit list when your abductors strike. By which time it will be too late.

This is not a hoax. Blast Theory group member Matt Adams calls it a legitimate service for the public. ‘We are actually going to take the risk of going ahead and doing it. It's a contract between us and who we are going to get,’ he says. This contractual commitment is so important that it's even possible for would be victims to design their own bespoke kidnapping. Matt explains: ‘You can pay to have a complete scenario acted out; you could be the rich son or daughter of a millionaire who gets kidnapped for ransom and we will give you the full fictional representation.’

But why kidnap people in the first place? Of course, it's all a matter of art. Blast Theory began in 1991 as a collection of eight artists with a shared passion for film, clubbing, performance and going to gigs. They all held down jobs at the Renoir Cinema in London where, as Matt explains, they ‘used to sit around between movies talking about doing something apart from tearing tickets’.

The fledging company set out to create performances for a broader audience than the average theatre crowd. Their early shows, Gunmen Kill Three and Chemical Wedding, were promenade events which combined video projections and audience participation with live performance. The aim was to create special events which harnessed the raw energy and creativity of the club scene at that time.

Seven years and five major performances behind them (including Something American, which won a Barclays New Stages Award in 1996), Blast Theory have grown tired of touring their ambitious multimedia shows. From the original line-up, founder members Matt Adams, Ju Row Farr and Will Kittow remain, alongside Nicholas Tandavanitj who joined them three years ago. Over the years they have all grown dissatisfied with the state of the arts funding system and with the lack of support from venues for large-scale touring work.

Blast Theory's problem is, unsurprisingly, a predominantly financial one. As the work has progressed, the use of new and larger scale technologies has grown to the extent that touring has become financially untenable. As Matt explains: ‘Something American was costing us about £2000 per venue and all we were able to charge was maybe £750; so we were losing £1,250 every time we set foot anywhere.’ It was time to look for a new direction. This explains how, as Matt puts it, ‘we came to the point of thinking that we should kidnap people’.

We talked about kidnapping someone for twenty minutes... just throw them in the back of a van, drive like crazy and throw them out again in some wooded area with fifty quid, drive away and just leave them trying to explain that

Blast Theory never intended to be ‘just another touring theatre company’, and they regard Kidnap as a chance to extend their artistic interests beyond the boundaries of theatre. They have always sought new ways to challenge audiences with their performances, and in the past have not been afraid to use either confrontational or controversial techniques to achieve their goal. Kidnap is both their most ambitious project to date and unquestionably their most attention grabbing. It also allows the company a rare chance to create work which is shaped by the audience as Matt explains: ‘We are embarking on an event where the outcome is really in the hands of our audience.’

Kidnap cannot be rehearsed. The company have no way of knowing who will register for the project, what the result of the random selection process will be, or how the two selected individuals will respond to being held in captivity. It promises to be a very unusual performance event. As Matt says: ‘it's a hybrid between a game, an adventure sport, an artwork, a media stunt, an intervention and a happening’. But isn't it also a crime?

Not exactly. When they register, all potential participants give their consent to being surveyed, abducted, imprisoned and monitored. In a legal sense, this is not a kidnap at all. Blast Theory have spent the past months in lengthy discussions with lawyers to create a working structure for Kidnap which is within the law. They did toy briefly with idea of breaking the law, as Matt explains: ‘we talked about kidnapping someone for twenty minutes... just throw them in the back of a van, drive like crazy and throw them out again in some wooded area with fifty quid and drive away and just leave them trying to explain that’.

But this was never really a serious option. It wasn't only the fear of prosecution that led them to reject the idea; they were always clear that they wanted to create art and not anarchy. As Matt concedes, ‘If you kidnap someone against their will, you are starting to mess with [them] pretty badly.’

Artistically, Kidnap is a serious attempt to investigate why the media is so fascinated by violent crime. From the multiple homicides of Tarantino movies to the true crime reconstructions of Crimewatch UK, violence is the lingua franca of popular culture. As self-confessed 'passionate consumers' of popular culture, Matt explains that Blast Theory are concerned with discovering why violence has such powerful dramatic allure. Because the vast majority of contexts in which violence is portrayed do not question the violent act itself, Matt hopes that Kidnap will set the record straight.

This is not Blast Theory's first performance about violence. Invisible Bullets (1994) was made in direct response to Crimewatch UK. The company repetitively reconstructed a fictitious murder over a ten-hour period as a comment on the sensational use of dramatic techniques in crime reconstructions. In Gunmen Kill Three (1991), they asked an audience member to fire a gun point blank at two cast members as they walked the stage in their underwear. The gun was loaded with a paintball, but as Matt admits, ‘if it hit someone it would leave a bruise the size of a saucer’. This was Blast Theory's first attempt at deconstructing the glamorous way that guns are portrayed in films and on TV. Touted as designer accessories in Hollywood's action adventure movies, it can be easy to forget that guns have only one purpose: to kill. In the movies, holding a gun is like smoking, it's just another way to look cool.

In preparation for performance Blast Theory use toy guns as props in the rehearsal room. They find that performers of both genders are drawn to the gun with a mixture of dread and excitement. ‘To hold a gun is to hold an object of power, it is an empowering tool,’ Matt admits. It is possibly the appeal of power that excites audiences when they watch their favourite action heroes blast their adversaries off the screen. But like the popular movies they so enjoy, can't Blast Theory be accused of glamorising violence? Or worse still in the case of Kidnap, of trivialising it?

Whilst Matt refers to the project as 'fun’ and ‘exciting', he acknowledges that Kidnap ‘has the capacity to really upset someone or damage someone's life’. He goes on: ‘That's why we've been so cautious about planning it thoroughly, because even with the best intentions it can be easy to end up with the glamour side of it and to forget about what we are originally intending to do.’

Beyond the sensation of the actual kidnapping, there is serious artistic enquiry behind the project. In the forty eight hours following the kidnappings, the two hostages will be held together in a safe house. Their interaction during this time will be monitored by concealed video and audio surveillance equipment and simultaneously broadcast live on the world wide web and to one remote site (possibly a gallery or a cafe). Anyone can hook up to the event and thus participate in the project as it unfolds. The broadcasts will eavesdrop on the kidnap victims as they cope with the period of incarceration.

The outcome, of course, is unpredictable. Whilst Blast Theory have put months of meticulous planning into the event, once it begins they have no way of knowing what will happen. Indeed, either or both of the participants could choose to quote a preordained safe word which will guarantee their immediate release. But this is part of the project's appeal. They have even made life harder for themselves by offering a £500 cash pay out to the participants should they escape before the forty eight hours is up. Should they fail, they will be released unharmed at a press conference at the end of two days.

Blast Theory hope the media will play a major role in the project. They have hired top PR consultant Mark Borkowski to handle the press and from the launch through to the closing press conference, Kidnap will, in many ways, be an exercise in media manipulation. Borkowski has no doubt that the event will make good copy. They are all, however, keeping their fingers crossed that the project is not launched on a day when the papers are full of headlines about kidnappings in the former Soviet Union or the Middle East. They could be in for some flack if they're unlucky.

Otherwise they hope the media will be attracted by Kidnap's sensation factor in the same way that the K-Foundation's stunts proved so media friendly a few years ago. It remains to be seen whether their relationship with the press will be symbiotic or confrontational, but every column inch will give Blast Theory a little more of the public profile they crave. As Matt admits, ‘it was always our aim to make work that demanded people's attention. The Kidnap project was not designed to be sensational, but it has its sensational elements which I like.’

To register for Blast Theory's Kidnap call 0800 174336 for details now. The project is scheduled to happen in June.