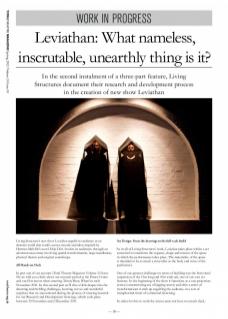

Living Structure’s new show Leviathan engulfs its audience in an abstract world that recalls scenes, moods and ideas inspired by Herman Melville’s novel Moby Dick. It takes its audiences through an adventurous journey involving spatial transformation, large installation, physical theatre and original soundscape.

All Hands on Deck

In part one of our account (Total Theatre Magazine Volume 23 Issue 04) we told you a little about our research period at the Pinter Centre and our first moves when entering Trinity Buoy Wharf in early November 2011. In this second part we’ll dive a little deeper into the daunting and thrilling challenges, learning curves and wonderful surprises that we encountered during the process of creating material for our Research and Development showings, which took place between 30 November and 2 December 2011.

Set Design: From the drawings to the full-scale build

‘As in all of Living Structures’ work, Leviathan takes place within a set conceived to transform the expanse, shape and texture of the space in which the performance takes place. The materiality of the space is intended to be as much a storyteller as the body and voice of the performers.

One of our greatest challenges in terms of building was the horizontal suspension of the 15m long and 10m wide sail, one of our core set features. In the beginning of the show it functions as a vast projection screen (a mesmerising sea of lapping waves) and after a series of transformations it ends up engulfing the audience, in a sort of metaphorical ritual of communal drowning.

In order for this to work the screen must not have too much slack, but the bulk of the fabric turns out to be far too heavy for the ratchet straps that were supposed to tension it. Everybody has been involved in working on the structure, bolting rostra, sewing and hemming the vast sheets of fabric. This was supposed to be a moment of ‘moral boosting’, where everyone would marvel at the striking image of the stretched sail, but now it hangs in-between the rostra like a wet towel. I hasten to ensure everyone that this was to be expected and that all we need are some minor adjustments and some better ratchets. This is true – I really believe that it is but I also know this is only the beginning: we still have to find a way to raise the sail, and to lower and stretch it out above the audience in the end.’

Klaus Kruse, process notes

Costume Design – When Russian Constructivism meets reality

Early in the planning period we established that we were to give great attention to the costume designs for Leviathan and that we would collaborate with professional designers for this. Klaus brings a vague idea to the table: basing the costume design on geometric shapes. Ula picks up on this and consolidates the idea, introducing us to a selection of costume designs from Russian Constructivism. The group gets very excited about it all, to the point that we decide we’d like this style to be the basis for our overall visual aesthetic.

In early devising sessions at the Pinter Centre, we had started to work with yellow raincoats. We had devised some really solid material with this element but the bulky shapeless yellow raincoats were the absolute opposite to the strongly defined geometrical pattern that we had now chosen to work with. Our costume designers Philippa Thomas and George Ellison were confused and we didn’t seem to be able to pinpoint what we really wanted. For several days everything felt up in the air. How to make a costume based on geometrical shapes that can also work in terms of flexibility and clarity of movement? Time was running short and we needed to make some concrete decisions in order to insure the confectioning would take place within our deadlines.

In a desperate attempt to save Russian Constructivism, Ula, who never in her life had used a sewing machine before, whipped up a pair of trousers in style (using Gaffer tape to give the illusion of a crotch). There was much discussion – and almost tears – over lines, angles and tastes but over the next couple of days George and Philippa designed a prototype that worked without the Gaffer, which everybody loved.

Set Building Versus Rehearsal – A conflict inherent in our work

‘Living Structures’ sets are designed to physically transform space. The devices we use for this are mostly very low-tech but fairly complex from an operational point of view. The mechanisms we construct are usually primarily hand operated by the performers, as part of the performance. Our work always responds to some specific features of the spaces we perform in, but fundamentally creates environments that are self-sustaining.

The entire cast and crew contributes to the building and making of set and props. Over the years we have refined areas of expertise within our team of long-term and project-based collaborators but overall Living Structures’ processes are still very hands-on on all fronts. This ‘everybody does everything attitude’ has both positive and negative implications. On the one hand there is a great spirit of shared ownership over the space design, on the other, there is a tendency for the building aspect to take over and to infringe on rehearsals.

We were already half way into our time at Trinity Buoy Wharf. Some excellent scenes had been created but we desperately needed to develop more performance material from within the space. We needed to devise, to improvise with our set and with each other. We knew that what could emerge from this interaction was beyond anything we could imagine by thinking alone, but there just never seemed to be enough time.

In a way, in Living Structures’ work, things are never entirely ready. New ideas and possibilities always come up and often they require minor (sometimes huge!) adaptations to the set and props. But our problem at this stage was that not even our initial set ideas were ready. We’d been a bit ambitious (again!), and there was still a lot of work to do.

We’ve been very good in keeping up with our yoga sessions at the start of each morning. The whole group seems to agree on how this new routine has been really great for our physical maintenance and creative focus. But we are also all starting to get very anxious about how much the set building is seriously infringing on rehearsals. I keep reminding Klaus that we have to make more time for scene study and devising and we become very aware that things will never be ready for this unless we decide they are, unless we give them a cut-off point. We need our performers to be as strong as our visuals and so we begin to find strategic moments in which I take core performers aside to work on various exercises (presence, precision, strength) whilst Klaus and other builders advance with the set.’

Dani d’Emilia, process notes

‘The lack of time for exploration transpired similarly in our vocal work and we were confronted by the difference between the vocal pieces that were composed outside of the rehearsal process and those that were devised within rehearsals. Verity’s luscious compositions often involve incredibly complex harmonies, so often there was some difficulty when trying to bring them into the scenes as performers couldn’t be too dispersed in space, breathless or in awkward physical positions. Scenes often had to adapt to songs.

Although pre-composed songs form an important aspect of our work I realise now that we need to give more time and space to voice exploration in order to progress the work towards a voice and movement approach that is more integrated, experimental and artistically challenging.’

Klaus Kruse, process notes

Setting Sail

Amidst the various spatial, temporal and financial challenges the show started to take shape and we finally got the sail tightly stretched across the space. We bathed in the magnificence of the image of Dugald [Ferguson] emerging from the sea and magically swimming across to the sound of whales and mourning widows. Many more striking moments started to come together, the space became a player in its own right, a part of the ensemble. Though we were only preparing for research and development showings, clearly a new grand vision of Living Structures was coming alive.

To be continued…

This article is the second of a three-part series that documents the development of Living Structures’ Leviathan. This instalment was written by company members Klaus Kruse and Dani d’Emilia.

Leviathan has been in development with the support of Arts Council England, The Old Vic Tunnels, University College Falmouth, Trinity Buoy Wharf and The Pinter Centre (Goldsmith University of London). The show will premiere later in 2012.

Living Structures was formed in 2007 by Klaus Kruse, Dani d’Emilia, Ula Dajerling, Verity Standen and Dugald Ferguson.

For more information about the company and its artists, and about Leviathan and other works, see: www.livingstructures.co.uk