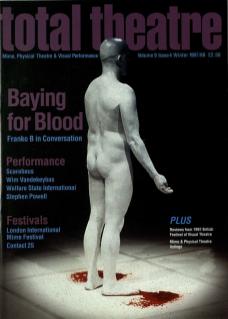

Cast your mind back to 1977: Abba were in the charts and flares were in fashion. Nothing much has changed. Twenty one years ago a young Joseph Seelig was artistic director of the first Festival of Mime and Visual Theatre. In 1998 he still directs the London International Mime Festival (LIMF) alongside Helen Lannaghan.

Lannaghan describes how she quaked in her boots when she first met Seelig, whom she describes as a 'morose, lugubrious figure'. Now they evidently form a strong team. Seelig comments that the festival 'really became a profitable outfit' when Lannaghan came on board in 1987. She seemed an unlikely candidate for festival director, having studied Oriental Geography at SOAS. She is also an accomplished graphic designer, designing print for companies like the RSC and DV8. She was, however, bowled over by seeing Marcel Marceau at the age of fourteen and later did stage management for her then boyfriend, Ben Keaton, who thought (like David Bowie, Kate Bush and Lindsay Kemp before him) that studying mime would be one route to becoming a famous rock star. She met Seelig when, using her grant cheque as a stake, she and Keaton hired The Place Theatre and presented John Mowat's London premiere. The show was a sell-out. Lannaghan got her grant cheque back, and Seelig instantly recognised her potential. Today they work together in a large office with silver plaques on the door beside the British Museum.

Both Seelig and Lannaghan are passionate about mime, and as directors of the longest established and best-respected mime festival in the UK are clearly in a position of quite considerable power. Seelig states their objective is to: ‘Promote the artform to as wide an audience as possible. We want the real public to come – we don't want to ghettoise it – we believe in the work and we think loads of people should come and see it.’

Seelig defines mime as: ‘Work which is not text based, whose motivation comes from visual and physical skills rather than from a text. It's not about actors flapping their arms about... Some shows do have words but they are kind of incidental.’ Lannaghan says that her ideal festival would be one where: ‘Not one word was uttered.’ She complains that actors speaking can ruin a show: ‘Very often the power of the thing just drops. Unless you are someone like Boleslav Polivka (described as “playing the theatre like a Stradivarius”, and being “a cross between Danny Kaye and Richard III”) who really can do everything brilliantly, then you should really concentrate on one artform. Mime is a very powerful medium – you can take people to all sorts of places in their heads.’

However, over the years the festival has moved quite far away from mime. Nola Rae, who teamed up with Joseph Seelig twenty years ago to establish the first Festival of Mime and Visual Theatre, likes the way the Mime Festival now delves into so many corners of performance. ‘Lots of things they programme are not mime at all,’ she says.

Back in 1977 actors were only just beginning to consider a mime training, perhaps in Poland or with Lecoq in Paris. Seelig, then programmer at the Cockpit, remembers that mime ‘was an area of work which was under publicised and totally neglected’. To address this problem, he got together with Rae and invited eleven artists to perform at the first festival at The Cockpit Theatre. Participants in the festival were: Nathaniel (an American mime), Sony Hayes Magic Fantasy (a group of idiosyncratic cabaret performers), Theatre Slapstique (modern Commedia from France), Marita Phillips (with work choreographed by Adam Darius), Justin Case (magician, acrobat and unicyclist), The British Theatre of the Deaf (deaf, sign and mask), Annie Stainer (clown), Chris Harris (actor, mime, clown), Mute Pantomime Theatre (more Commedia), Desmond Jones, and of course Nola Rae.

The Cockpit was full every night and, after that first year, the festival took off in a big way with other venues such as the ICA, The Place and BAC programming performances. The following year, in 1978, the festival became international with artists from Argentina, USA, Germany, Switzerland and Holland.

It is fair to say that LIMF was the first international theatre festival in London. Seelig points out that there was the World Theatre Season, but Dance Umbrella began the year after LIMF and LIFT did not begin until 1981. Charles Hart of the Arts Council panel, which has funded LIMF since its inception (they received £1500 for the first festival), says that LIMF has been responsible for ‘setting the standard for mime and physical theatre in this country’. The international perspective has enabled UK practitioners to place their work in a broader context and has promoted the exchange of skills and influences. However, the international focus of the festival, Rae believes, can mean that non-British artists are favoured at the expense of UK based performers who are now not getting the support that the festival once offered.

Lannaghan and Seelig are proud of having had the opportunity to ‘raise the temperature' on certain companies and provide their work with a valuable platform over the years: Complicite, The Right Size, Trestle and David Glass among others. Seelig says: ‘I take my hat off to them. Mime is a rare art and the festival is important because it keeps a focus on the artform.’ He does worry though that, after twenty years, they have still not been completely successful in getting the message about mime across to a mass audience. As Rae points out: ‘We seem to be still discussing the definition of mime just as we were then.’

Seelig is concerned that some companies have now dropped the 'mime' label, saying that the word has actually hindered their professional development: ‘Venues might say “we've had a mime here this year, we can't possibly book another one”, or the press might say “oh we've done mime this year”, throwing all the work together in one category. Crazy surely. When will the press find the vocabulary to talk about this kind of work? Steven Berkoff is, after all, a great mime although he has never been in LIMF. He's a very busy bloke isn't he? He makes movies in Hollywood after all.’

Seeling was astonished recently when a critic from Time Out asked him, in all seriousness, what devised theatre was: ‘He simply did not possess the vocabulary to talk about this kind of work.’ At least, although theatre critic Michael Billington ‘hates mime’, he ‘does write about it appreciatively sometimes’.

So how do practitioners get programmed into the festival? Seelig says that even after twenty years ‘everybody in the world writes to you’. If something grabs their attention, Seelig and Lannaghan will ask the company or performer to send a VHS of their show: ‘If the video is interesting we will go to some lengths to see it live. The show must be a London premiere and it's sadly not a free for all, the risk is very big for us and we need to keep our audience. If a company cannot afford to make a video we will however go and watch a rehearsal.’ Remember though, if you do send a video send the whole show; Seelig worries about the bits that have been left out if you only send an edited version. Likewise, don't try to make your show look better that it actually is. The competition is enormous.

Both Seelig and Lannaghan dream of being able to commission more work. Lannaghan's personal dream is of a flexible venue in the centre of London with ‘a 500 adaptable seater, state of the art equipment, a wonderful rehearsal space, a video library and resource centre for mime and physical theatre’. Here, she would bring together artists such as Patrick Bonté & Nicole Mossoux, Lloyd Newson, Nigel Charnock, Bruno Meyssat, Josef Nadj, and Derevo to create new work together under one roof.

Seelig dreams of being able to afford some of the continental companies for whom the draw of London is fading: ‘We would like to be able to pay people more... In the end you run out of reasons why an artist should come to London. I want to be able to say "how much do you cost?” “Oh really, OK, no problem, we'd like to invite you to LIMF next year.”’

1998 is LIMF's twenty first anniversary year and with the enormous explosion of visual, mime and physical based theatre in this country and abroad it is obvious that the foundation laid by Seelig and Lannaghan will last well into the next century. There is nothing to beat the buzz of a live event, and as Lannaghan says, ‘being part of a living, breathing organism that is called a "full house” is a totally wonderful experience.’