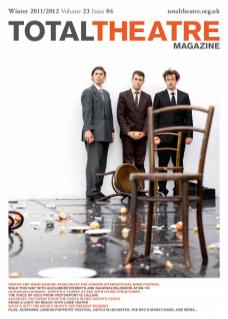

London’s celebrated Little Angel Theatre inaugurated the Suspense Festival of adult puppetry in 2009, both responding to and feeding a growing appetite for puppetry within more mainstream adult theatre fare. Their efforts were rewarded with excellent audience figures, a number of new north London venues programming puppetry and a Fringe Report Award for Best New Festival, as well a shortlist placing for the Peter Brook Empty Space Award.

The festival for 2011 is that notorious second album – there’s a pressure of expectation and artists and venues wanted to be involved in greater numbers, perhaps hoping for a taste of the War Horse effect in these tough financial times. Suspense 2011 programmed more than 30 shows, spread across eleven venues, including larger-scale houses such as the Roundhouse, and incorporating the V & A Museum. I cherry-picked seven productions over the nine-day schedule to try to get a taste of where adult puppetry in the UK is at today, and what might be the trajectory of an artform whose popularity seems to just keep on growing.

My experience of the festival was bookended by two productions exploring shadows and projections – a puppetry form that relates less immediately to the public perception of puppetry featuring scaled figures and skilful hands. Skilful fingers, however, were much in evidence in Nutmeg’s labour of love The Invisible Cities of Margherita Monticiano. The production, developed in collaboration with Norwich Puppet Theatre’s new director Joy Haynes (of Banyan Theatre) was a series of re-imaginings of the city of Venice, conjured through overhead and video projection with shadow work, all focused onto a single screen in a rickety booth – most satisfying in one sequence when it was reversed to show its struts and workings.

Influenced by Italo Calvino’s Invisible Cities, these are sidelong characterisations of place where the real and imaginary blur: one city is defined by its populace’s inability to actually connect so obstructed are they by their vivid fantasies of one another. Perspex slides and the less tangible qualities of video projection intermingle to create images that can be wonderfully sensual and the whole is very eclectic, populated by diverse cut-outs, drawings and shadows, creating a bricolage effect reinforced by a highly diverse musical score.

The production was presented as a work-in-progress showing (though not framed as such in the festival programme) and some progress is needed, principally in the relationship of the two busy performers to the audience and the material – they worked like craftsmen but were being used as performers, and their understated movement and presence muddied the storytelling.

This is a not uncommon problem in the puppetry field and the increasing focus on the artform triggered by its growing popularity places growing pressure on practitioners to up their game in performance terms. It is partly a question of formal placement – exactly what type of work is puppetry creating? It’s tempting to identify the form squarely within theatrical terms (theatre’s ‘lost limb’ as Adrian Kohler of Handspring is quoted as saying in the festival programme), however indefinitearticles’ work increasingly seems to situate it in more of a live art frame.

Their new production, Penumbra, amply illustrates its credentials as a collaboration between puppeteer and visual artist, as well as between husband and wife. This is a tender performance as much about the intimacy and familiarity between two individuals who draw one another with light, with colour, with pencils and puppets, as it is about the medium they use. Steve Tiplady and Sally Brown create a series of images saturated in colour and light via projection, coloured gels, and the shadows of their own bodies clothed and, later, naked. The abstract coloured shapes, cut outs and shadows reminded me of Matisse and, after a slightly late and much-needed framing explanation (of the story of the first image, drawn around the shadow of a husband his desperate wife was about to lose at sea), the steadily accumulating connections of desire, time, shadow and image begin to build toward something gently satisfying. However, I found the offhand relationship the pair established with the audience distracting, a slightly uncomfortable concession to ‘theatre’ that felt alienating. There’s real experimentation here, but again the place of performers (and audience) within it remains ill defined.

Hit Gelamp’s production Madeleine on Tiptoe was also interested in shadows, revealing the story of nineteenth century ecstatic Madeleine through the eyes of the psychiatrist who treated her. This production formed part of a seam of young companies running through the programme, including work from Pangolin’s Teatime, Eye Spy Arts, Folded Feather and Maison Foo, demonstrating puppetry’s continuing appeal to emerging artists. In this case, the idea – connecting the figure disappearing into two dimensionality with the symbolic transformation of Madeleine for her doctor, of individual to icon – reached further than the execution could, hampered by some all-too-visible theatrical devices and a rather odd acting register.

In Little Edie we found an established puppet theatre company, Pickled Image, taking a sideways step. The company are here retelling the true story from a famous documentary about a destructive mother-daughter relationship, locked in a decaying mansion (beautifully conjured by the company’s trademark slightly gothic, cartoonish design) and in memories of another time. Octogenarian Edie pets her cats (some dead, some living), festers in her bed and in turn bosses, berates and comforts her strange daughter; Little Edie meanwhile piles rubbish up against the walls, rails and panics at the outside world and reminisces about her dreams of becoming a star.

It was great to see visually arresting largescale puppets in action with some delicately played payoffs in the dance sequences (showcasing two shapely pairs of real bestockinged legs behind a single figure), but there were some problems with the form. Naturalism is always a difficult choice in puppetry, its rhythms are often wrong and, despite gradually drawing us into this esoteric world, the production never really answered the question of why they wanted to retell this story.

Autumn Portraits, by US-based Sandglass Theater likewise focused on characters of a more mature disposition, occasionally (though not enough) touching on the philosophical (and puppetry focused) issues of age, dying and control. Co-founder Eric Bass is a master craftsman and the beautifully honed vignettes were perfect little morsels of puppet design, lighting and rhythm – if never quite building into a full meal. This awardwinning production was first made over thirty years ago and has toured successfully ever since, and the highly atmospheric and characterful figures peopling its five discrete scenes intriguingly conjured up puppetry past. But we demand more now from a form once prized only for its artistry – we want drama, we want performance, we expect art as much as craft!

There were moments when Wild Theatre’s Stonebelly delivered this, and I was very happy to see some pure object animation in this year’s programme. Performed on three freestanding circular plinths, each covered with sand, Wild Theatre gradually unearthed a range of objects – detritus – collected from their native New Zealand tideline. The objects disclosed themselves gracefully, and her commitment to them was such that we could appreciate the characters from within their form even when they didn’t become figurative. As objects landed heavily and explored, fought and traced art in the sand, which occasionally swirled sensuously over the spinning rim of one of the drums, the theme was of the life lost through the cracks, residual in discarded objects. This underlying exploration was at times more or less clear within the highly abstracted form supported by its discordant and diversely detailed score by Hannah Marshall, but it was always beautiful, reflecting the care, skill and commitment of performer Rebekah Wild. When the ‘cello+’ score finally resolved into a melody line for the final sequence the effect was joyous – a soaring harmony to accompany the life-affirming dance of a crack-mouthed driftwood figure.

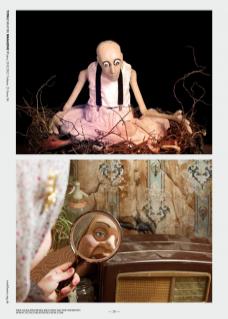

Plucked was undoubtedly my festival highlight. Created by Liz Walker, formerly of Faulty Optic and now heading up orphan company Invisible Thread, this was a ‘true fairytale’, a re-casting of ancient tropes of romance, parenthood, and witchcraft into a different frame, shaped by bitter experience and a taste for the absurdity of life. The life-story outline was lightly sketched, thoroughly weird and rendered entirely believable and full of heart by the evocatively detailed puppet characters. Romance here between two bird-like yet human figures with silver pin-head eyes is the thinnest of affairs – a chance meeting looking for worms, a ‘house’ set up with a single rickety plank slung between two ladders (I can’t right now imagine a better visual metaphor for the hopes we erect in the flimsy architecture of human relationship), some uneven stumps of wood to demarcate the edges of their world. And yet the delicacy of their reactions and interactions with one another – the coy and nervous glances of the initial encounter, the glances of shared joy that amplify pride in becoming a family, the tenderness of touches to comfort loss – create a recognisable emotional world that is both profound and touching. The puppetry is astonishingly good – every breath, each shift in rhythm communicates with us richly.

This emotional grounding allows us to follow the piece deep inside its delicious weirdness. This is a world where childbirth produces an array of unexpected visitors (some delightful surprises I’m not going to spoil here) and, at the end of a relationship, the family can simply fly away. It would be tempting to read these rich actions metaphorically but such is the production’s commitment to this material logic that the possibility opens up to simply accept the objects and events on their own terms, and this reading feels richly rewarding and rather unsettling.

Sex, however, is still sex – and to say there’s a priapic theme running through the show would be an understatement. In the second act the willowy if episodic lovemaking of the protagonists is replaced by an aggressive anti-men (or at least anti-cock) rampage as the abandoned woman takes on the mantle (literally) of the crone (or crow, here). I really enjoyed the horny, hairy wolf who has colonised the booth of Mr Punch (himself no stranger to an extended erection) and you can feel in this production Walker stretching her wings to demonstrate the formal breadth of her puppetry imagination.

There is a powerful marriage of form and content here: for many people puppets are part of the language of fairytale – their strange charms lend themselves readily to magic, transformation and an epic scale. Yet Walker’s puppets have always also been about struggle, suffering and downright weirdness and it’s this tension that is most satisfying. The show throws together the best of human relationship and the worst of human emotion – it is powered by our frailty and effort and need, supported by the relentless architecture of folklore and fairytale.

Suspense 2011 offered a big programme curated by a small theatre – the Little Angel – that is Britain’s crucible for puppetry. It was an ambitious venture, delivered under the guiding hand of Peter Glanville, who is artistic director of both the venue and the festival, and the programme included not only an enormous variety of performance work from all over the world but also a hefty number of masterclasses, workshops and discussions.

What Suspense highlights is that in practice, puppetry can be not one form but many. The festival prisms out some of the diverse influences and forms that converge in puppetry, continuing to demonstrate audience appetite for puppetry as visual art, as storytelling, as material theatre, and as emotional drama. It is at its most potent for me, though, when these forms and styles, embodied in the art of masterful puppeteers old and new, empower one another and work together.

Suspense Festival took part at venues across London, 28 October – 6 November 2011.

Beccy Smith saw the following shows: Nutmeg, The Invisible Cities of Margherita Monticiano at Pleasance Studio, 28 October; Sandglass Theater, Autumn Portraits at Little Angel Theatre, 30 October; Pickled Image, Little Edie at Jacksons Lane, 1 November; Wild Theatre, Stonebelly at Little Angel Theatre, 4 November; Hit Gelamp, Madeleine on Tiptoe at Pleasance Studio, 4 November; Invisible Thread, Plucked at Little Angel Theatre, 6 November; indefinitearticles, Penumbra at Roundhouse Studio, 6 November.

For more on Suspense 2011 see www.suspensefestival.com