Towards the end of last year, New Playwrights Trust (NPT) embarked on a project entitled Writing Live. This is an investigation of the current context and practices involved in the use of writing in live art work. The impetus for Writing Live stemmed from a recognition that as much as some would like to police 'new writing' within recognisable limits – even within a certain aesthetic – there continues to be a host of indiscreet couplings of writing with other disciplines going on under their very noses.

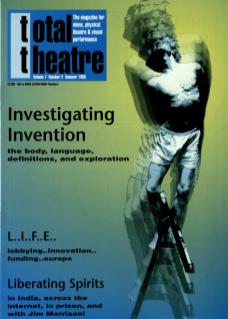

This desire to break down boundaries is of course far from new. What gives Writing Live an added urgency is the increasing desire of practitioners from other disciplines to use and challenge language and verbal text. This raises important questions, for example about the relationship between language and movement and the way in which they continue to be posed as opposites. It also has implications for training, funding, for the structures of professional relationships, and approaches within working practices.

A common attitude of movement practitioners is to privilege the physical over the verbal. Because movement is ‘visceral’, the argument runs, it has a kind of direct line to the audience, an immediate intuitive engagement that the text-based work with its focus on the ‘head’ cannot have. What this does not take account of is that there may be a whole range of different cultural perspectives within an audience which are redefining that ‘direct line’ even as it is made.

On a practical level, it is the role of an interpretative authorial voice which is treated with suspicion. Movement, it is said, because it is imagistic, has an ambiguity which frees the audience in its interpretations. Using language (and by extension, the playwright), can be seen as paring down the interpretative freedom of an audience due, in part, to the supposed specificity of their communication.

In MSM, by DV8 Physical Theatre, a clear decision was taken to allow the voices of the men to be heard verbatim. The strange power and wide diversity of the experiences and the attitudes of the men might well have been reduced by the interpolation of a writer, by the temptation to create motivations for characters and a linear narrative on which to hang them. However, the words of MSM were naturalistic; direct speech, though edited and juxtaposed. Yet, Lloyd Newson of DV8 in a recent interview said: ‘...there are hundreds of stories out there. There are subjects around that would make fantastic plays and, well, I don't see or hear about many new playwrights that are writing visual or imagistic scripts which go beyond the conventional narrative or naturalistic text [my italics]. We [DV8] not only write these new works, but have to find and devise languages for them. How many playwrights construct a new language every time they write a play?’

A common attitude of movement practitioners is to privilege the physical over the verbal.

Some new writing does operate as a kind of staged journalism and its cultural status is shored up by those mainstream critics that feel more comfortable with issue-and-text-based realism. Critics are, after all, journalists themselves. Nevertheless, the work of a young performance writer such as Aaron Williamson, for example, has a relationship with language which can never be that simple; which is indeed physical due to his own deafness. What this demonstrates is a new challenge to the stock positions of the language/movement debate and a new impetus in which writing is being reappraised as a new tool.

The question remains of how to use it. Writing Live is documenting four contrasting production processes focusing on the way in which writing is being employed in each case.

The first project documented was Muster, a piece by Gary Carter after Anton Chekhov's Three Sisters, with text by Anthony Pickthall. The merry whirl of authorship indicated here was given a further spin by the swift devising process based on the individual experiences and personalities of those involved: two dancers, an actor, a writer, and a designer along with the director. Perhaps as a result of their training, the dancers proved more open to simply picking up (and dropping) a figure, and did not feel the need to 'create a character', the notion of which the piece challenged thematically anyway.

Interdisciplinary work may not actually mean 'breaking down boundaries'. This approach is predicated on the notions of essential, defining qualities of disciplines, e.g. the very opposition of concepts of ‘language’ and 'movement' which set up a smoke-screen. Working from this assumption may make work which is actually more vulnerable to the criticisms of faddishness that still come from both sides of the 'new writing' / 'physical theatre' divide.

So the real artistic challenge may not be in getting writers to write imagistically or to write for movement but rather in the re-examination of the potential of each discipline in each process. This in turn perhaps demands the development of new vocabularies to talk about new work as a whole.