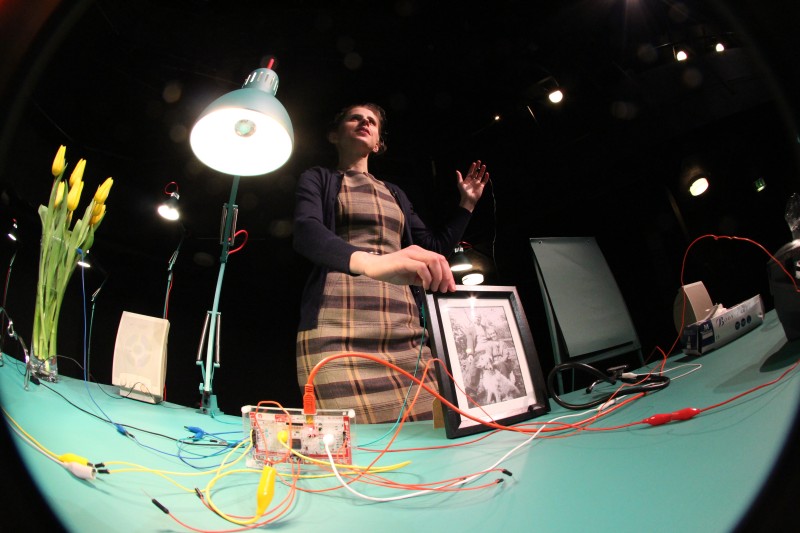

As a companion piece to the complexity and seriousness of (Total Theatre Award Shortlisted) The Eradication of Schizophrenia in Western Lapland, Ridiculusmus premiere this low key, high comedy two hander loosely framed around the archly metatheatrical concept of putting on a show. This durational art piece is (obviously) about a plague of mice whose main requirement is that everyone dresses in low-rent human-size mouse costumes – useful for a production whose many dubious characters are to be played by a cast of two. But where does the comic sub-story end and the actual show begin? Here lies the rub and it’s a most satisfying friction.

As a companion piece to the complexity and seriousness of (Total Theatre Award Shortlisted) The Eradication of Schizophrenia in Western Lapland, Ridiculusmus premiere this low key, high comedy two hander loosely framed around the archly metatheatrical concept of putting on a show. This durational art piece is (obviously) about a plague of mice whose main requirement is that everyone dresses in low-rent human-size mouse costumes – useful for a production whose many dubious characters are to be played by a cast of two. But where does the comic sub-story end and the actual show begin? Here lies the rub and it’s a most satisfying friction.

Satirising everything about where we are and what we’re doing (as an audience, as an industry, as the world), the show is unremittingly arch and consistently hilarious. At the same time as hitting its every mark, the material works as foil for the exploration of humans as vermin, the dehumanisation of the elderly, and the brutality of pest control.

This is a show that amply demonstrates the remarkable comic gifts and unique theatrical style that David Woods and Jon Haynes have developed together over the past twenty years. It’s very new, still a little underworked, and flags slightly in the final quarter – but it’s still, already, one of the sharpest shows you’ll catch in Edinburgh. It punctures every self-important bubble of the Fringe and offers a brilliant vision of a world when low grade pest control and high art combine in a completely unlikely and totally convincing concatenation. Once I’ve finally stopped laughing, I’m left reflecting that in the light of recent industry announcements, without Ridiculusmus on its books, the Arts Council’s portfolios will be an infinitely less rich place.