Boomtown Fair is more than a music festival with a bit of performance tacked on – it’s a full-on five-day immersive theatre event which invites you in to a living, breathing, fictitious city. Dorothy Max Prior talks to the festival’s narrative director Doug Francisco, to performer Ciaran Hammond, and to ‘citizen’ Frank Foster-Prior to hear their individual stories

‘A world of unity, creativity and freedom is what we aspire to achieve from our make-believe city’ says the Boomtown website. Founded in 2009, and set in the beautiful surroundings of the South Downs National Park in Hampshire, the festival titles each edition with a chapter number – emphasising Boomtown as an ongoing narrative. The 2019 edition, held 7–11 August, was called Chapter 11: A Radical City – festival attendees are encouraged to see themselves as ‘citizens’.

The ‘city’ is made up of distinct districts which have evocative names, such as Oldtown, Paradise Heights, Metropolis, and Copper County. Each district has at least one main stage and a selection of smaller street or theatrical venues, as well as small and medium-sized music venues.

There are also large stage areas (Lion’s Den, Town Centre, and RELIC) which are more like traditional music festival main stages – they accommodate crowds several thousand strong, with vast stage sets at the centre, and food and drink outlets.

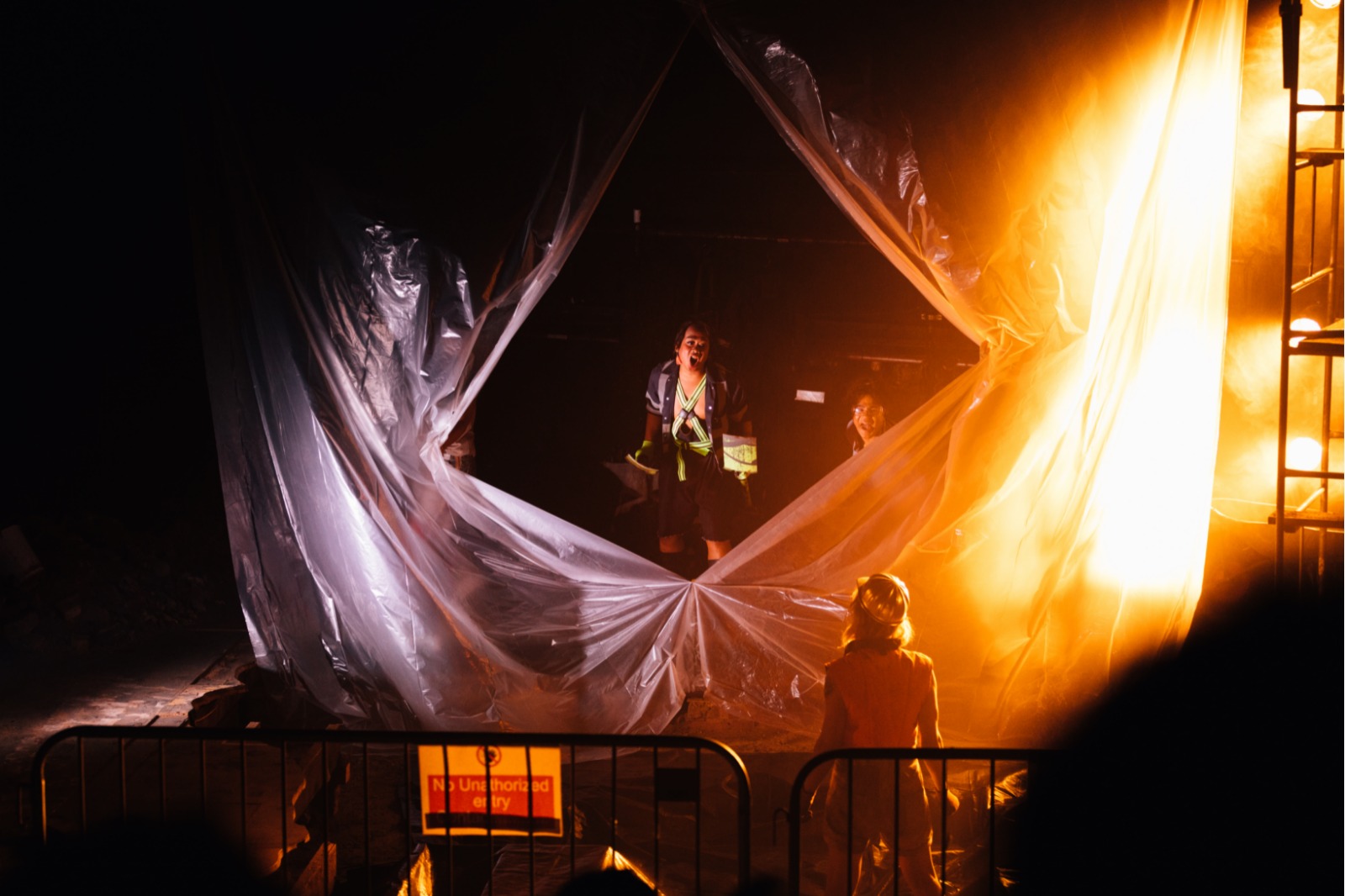

Boomtown Fair. Photo Charlie Raven

Each of the ‘districts’ has its own narratives and characters, made up from a massive pool of theatre companies, circus performers, and installation artists that help with the unravelling of a city-wide grand narrative which comes to a finale on the last day: ‘In following a particular mission or quest, audiences can traverse the entire festival, travelling between high-tech utopias, to a reconstruction of the Wild West, into a holiday land for filthy rich socialites from the 1980s, and finishing up in a cage in a pirate’s den. Interactions they encounter along the way range from intimate one-on-one installations, to helping to stage large outdoor happenings.’ (Boomtown website).

Performer Ciaran Hammond explains further:

‘Boomtown is split into districts which all have their own style and personality. This year, I was working in Paradise Heights, the uptown holiday-home for the uber-elite characters of Boomtown – and there were around 180 immersive actors in our district alone. Each district is comprised of outdoor music stages, and smaller street venues, all of which are styled accordingly to the district they are in. Some of these street venues exist solely for music, whilst others exist solely for the immersive theatre experience. One of our Paradise Heights venues, Villa Avarice, was an immersive venue in which core parts the narrative took place during the daytime, but for the evening it turned into a music venue.’

‘Citizen’ Frank Foster-Prior, who was on his third trip to Boomtown in 2019, wandered through Paradise Heights and describes it thus:

‘Paradise Heights is full of big fancy high-rise hotels and retail outlets… the interaction here is all about becoming an evil capitalist, and ultimately a VIP member of Paradise Heights.’

It even had a weekend-long No Tomorrow conference, in which characters had a ten-minute slot to give an anti-climate change TED talk – as Ciaran put it, ‘basically spouting bizarrely awful and backwards ideas about how to save the world’. Ciaran’s character this year was an evil fracking entrepreneur called Arthur Coalandoyle: ‘Essentially, I was recruiting audience members as think-tanks to help expand my fracking industry throughout Boomtown. I’d push their ideas right up to the limits of the absurd pastiche of consumer capitalism that Paradise Heights was all about, and then pay them accordingly, stating that I now “own you AND your idea”.’

Boomtown Fair: Oldtown. Photo Daisy Brassington

One of Frank’s favourite areas of Boomtown is the Bohemian Oldtown, with its dark alleys and colourful cast of Carny characters where ‘If you’re not careful you could get a bucket of water emptied over you from an upper window.’

Boomtown’s narrative director, Doug Francisco of The Invisible Circus, explains Oldtown’s key role in the development of the immersive theatre elements of the festival:

‘For Boomtown Chapter 1, The Invisible Circus hosted Oldtown, the city’s first immersive district, where the audience member could jump in and become part of the play – haggling with fishwives, pirates and brigands for clues and ways into hidden rooms, or more intimate theatrical experiences. That element has basically expanded wildly with the scale of the festival and more recently we have made this a city-wide quest where by all the smaller interactions – games, treasure hunts etc – tie into and circulate around the main narrative arc or theme of each year, which is revealed on the main stages as it develops with shows each night, culminating in a climatic cliff-hanger moment on the final night that leads into the next chapter.’

Another area of the festival is Town Centre, where you can find the fictitious city’s centres of government, education and employment. Frank again:

‘There’s a police station, a university, and a job centre with realistic queues, rude clerks and officious security guards. Last year, I went into the job centre and got assigned a job as a musician – I got given a toy flute and told to go out and busk, and had to earn some money to become a “professional” – which I did. This year, I went to the university (the Ivory Towers Academy) and studied art – drew some trees, to represent something that would save the world. I got some points, but “failed”, probably for too much blagging – my friend Emma got pulled off to a separate area and given loads of points and told she was a high achiever!’

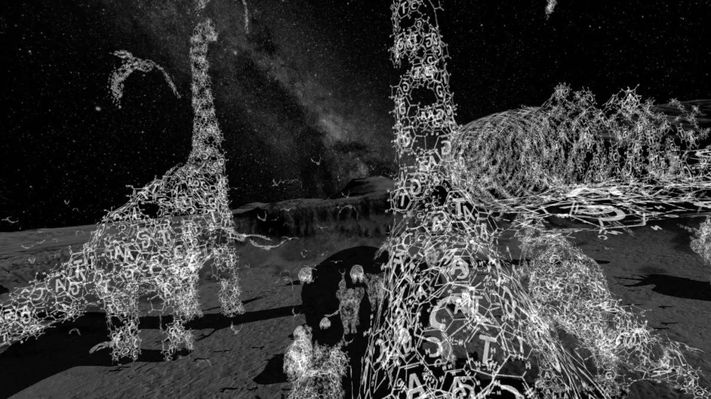

Boomtown Fair: Metropolis

Another of the districts (new in 2018 and developed for 2019) is Metropolis – musically, the home of House and Techno, in sharp contrast to Oldtown’s Balkan Beats and Folk Punk. Frank gives us his impressions:

‘Metropolis is a fancy, shiny city district dedicated to hedonism, the future and new technologies. There’s a Digital Funfair and a disco called Pleasuredome. One of its venues is called Little Pharma, where you can have your brain ‘recalibrated’. You can get attached to machines and be ‘assimilated’. I also went to somewhere that sold alternatives to soil – there was a brand called Zoil, which is supposedly a million times better than soil. I had a job interview to become an executive marketing director, or whatever, but I got kicked out for not looking the CEO in the eye – but Emma got the job! Then there was another area (outside Metropolis) that was all about soil testing, to see if it was safe – actual soil, not Zoil – we were given some edible soil samples…’

The level of interactivity – and the framing of Boomtown Fair as a fictitious city – is indeed unique in the festival world. But there are antecedents. The most obvious example is the theatre, circus and cabaret fields of Glastonbury – where many of the Boomtown creative team cut their teeth, and in some cases still continue to work. One of my favourite Glastonbury areas was Joe Rush and the Mutoid Waste Company’s Trash City, which spawned Arcadia (the later becoming a separate area in 2010). This was built around an enormous and wonder-inducing mechanical structure called the Arcadia Spectacular – a mighty metal monster that spun and pumped out light and sound, animated by live circus performance. At the creative heart of the performance element of Arcadia was Bristol’s Invisible Circus. The company’s artistic director, Doug Francisco, was also a mainstay of another favourite Glastonbury area – Lost Vagueness. This full-on, immersive, and theatrical venture was the size of a small village, and featured the Chapel of Love and Loathe (where guests could get involved in a whole cabaret of rituals, from marriage to divorce, bingo to boxing); the gourmet Silver Service Restaurant – an oasis in the midst of muddy fields; the Ballroom, featuring Come Dancing parodies and ska/punk/gypsy jazz bands – not to mention the casino, roller-disco, launderette, trailer park and sculpture garden. With burlesque and camp Carny elements a-plenty, Lost Vagueness even had an in-house ten-strong Can-Can team, Can-Booty-Can, choreographed by circus star KT Sarabia.

Showman Doug Francisco, Boomtown’s Narrative Director. Photo Andre Pattenden

So it is hardly a surprise to learn that Doug has been involved from the very start of Boomtown – and is now narrative director of the event. It is obvious from his work with The Invisible Circus and Boomtown that he has a fascination with the imagery and iconography of traditional circus and fairground, particularly in the ye old worlde travelling circus aesthetic of the Oldtown district, but prevalent throughout the festival.

‘There is such a magic and mystery in circus history – the roving heroes and clowns, daredevils and divas bringing tall tales and curiosities (true or false no matter) from distant lands; its place outside mainstream society, its travelling nature, often rebellious and revolutionary in its way, and also an equality ahead of its time. So it is indeed a rich and ancient tapestry to draw inspiration from, having held everything within its temporary walls at one stage or another. It also has a strong connection to the common people (so to speak) – it always was, and still is, accessible. But you have to respect its tradition as much as be fearless to take it into new dimensions: we were always a bit too contemporary for the traditionalists, and a bit too traditional for the contemporaries, which I loved and still do.’

In Boomtown Fair, there is an outlet to take circus, street theatre, and immersive performance into those fearless new dimensions – away from the restrictions of the regular performance circuits. Here is an audience of people who might never (throughout the rest of the year) go to a show staged in a theatre or circus tent, but are more than happy to be actively engaged in it all within the festival setting. As Boomtown has developed over the years (it is now a well-established fixture on the summer festival circuit), the audience has come with it. Many people return year after year, and some take the donning of costumes – or indeed of fully developed characters – very seriously, and throw themselves fully into the interactive theatre elements.

Ciaran says: ‘The audiences at Boomtown are the most generous and giving audiences that you’ll find anywhere in the world. Whilst their openness allowed me to test and try new ideas and methods, it also challenged my reflexes. As they’re so into the narratives, games and tasks that are hidden throughout the city, it’s immensely hard to decipher whether some of them are fellow performers or not; the characters that some of the punters come as makes it seem like they’ve been rehearsing all year round (and maybe some of them have!).’

Boomtown Fair – performance everywhere!

The carnivalesque blurring of roles is something that is at the heart of Boomtown Fair: who is performer, who is guest? Both merge into a total environment, jointly creating a shared fantasy.

This shared fantasy, of course, takes a lot of work to develop. Doug explains what his role as the festival’s narrative director entails:

‘A lot of writing of the kind of top-line titles, threads and briefs that feed into all the other departments and venues; and coming up with the over-arching arc, which I then confirm and develop a bit further with my co-theatrical director Martin Coat from The Dank Parish. We then work with the Boomtown creative producer Mair Morel and co-producers Michelle England and Sophie Shaw to further devise, disseminate and deliver this across the entire festival. So its a collaborative process, but we all have our defined roles and responsibilities.’

And from Ciaran’s perspective as a performer:

‘Within our district, Paradise Heights, we had five venues and each venue had its own director and actors. Each venue team would devise their content, characters and narrative as a team, with direction from an overall district director, to make sure all the venues are connected by a district philosophy. This philosophy is an outlook on the world that all the characters have and the district embodies. The devising process began with discussions around the district’s philosophy and attitude, so that all the venues were united in this. Once this was solidified we started working on immersive tracks and interactions that tied into the festival’s overall narrative and explored the district philosophy. Rehearsals were short and sweet, and focused on developing the key elements. But because the performances are interactive, they are based on what the audience bring to us, so we discovered a lot of the material as we performed it. This meant that we were given a lot of trust as performers to self-direct and devise on-the-go once we were out in the depths of the festival.’

From Frank’s perspective as an audience member:

‘I love exploring all the districts, interacting with the actors in-character, seeing a band of strolling musicians or circus artists go by, and picking up on stories from wandering around and stumbling across things. One of my best experiences was in 2017, my first time, just scouring Boomtown for hours and hours on a Saturday night. You’d go into a side alley, and there’d be your grandma’s house, but there’d be a bunch of people in there having a rave. And sometimes you’d discover something that maybe only five people got to see.’

Boomtown Fair Chapter 11, August 2019: Performers? Citizens? Boundaries blurred

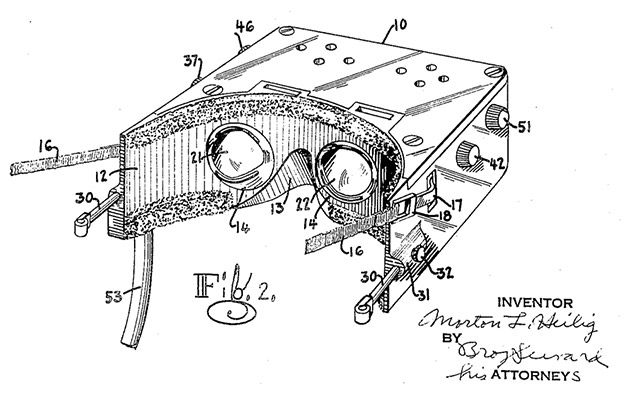

Frank has been to Boomtown three consecutive years now – on the first two occasions as a regular punter, and in August 2019 on behalf of Total Theatre, to check out the immersive elements of the festival, and to test-drive the new Access AMI app http://accessami.com/ developed to give another dimension to the interactive theatrical elements of the festival, and to turn the experience into something more like a live interactive video game. There have been apps for previous editions of the festival, but AMI (the acronym stands for Artificial Machine Intelligence) is a step up. The growing connection and interaction between digital Alternate Reality Gaming (ARG) and live action is something that Boomtown is pioneering.

Citizen Frank explains further, from his perspective:

‘At the end of the 2018 festival’s closing show, there was a big story about hackers getting into the system and taking down the government of the city, and now AMI is the answer – she’s been brought in to fix everything. Although we don’t know the exact specifics of who is up to what…’

As the Boomtown website puts it: ‘The mighty Bang Hai Corporation was toppled in the end by its own Machine that could not be stopped! Now omnipresent in all systems, AMI is everywhere. Though life seems to be going on as normal, strange new ecosystems are erupting from the Relic that was formerly the Bang Hai Towers corporate epicentre… Who will save us? No one but ourselves! The time is now to become a player in the game of survival and the most urgent and epic chapter in history. We must become the change we seek!’

Frank picks up on how it all works:

‘You download the Access AMI app, and there’s a map of Boomtown and all the different locations, the districts – like Copper County or Oldtown. They each have an icon, and you click on it, and there’ll be something, a snippet of news, a hint of what’s going on, and you go to the area – say, for example, it’s Copper County, where there was a storyline about an explosion. You had to ask around to find out what had happened – the actors are all in character, in period costume, and you have to try to get the information out of them. So we saw a broken window, some broken machinery… and there’s a QR code in the broken window, which you scan to get your point and move you along in the game. So every district you go to, there are these interactive performance elements, linked to an evolving story… ‘

And the AMI app is not the only digital support for the story – clues, riddles, characters and storylines also play out on other platforms, such as Instagram, Twitter, and Facebook; and via websites, podcasts, and VR. So there are multiple sources of narrative within Boomtown, virtual and otherwise, as Frank explains:

‘There’s a newspaper, an actual physical newspaper, which is “in ‘character” talking about the districts and the storyline. You can piece together bits of information from the newspaper, from shows and interactions in districts and venues, and from AMI and other sources, to work out what’s happening. I feel I lost track after a while… But some people are really on the ball and follow everything.’

And this is the point, and what is marvellous about it all – you can ignore the app and just wander about; you can dip in and out of the app; or you can follow the game fastidiously, amassing points till completion. A quick glance at any social media outlet will bring up thousands of posts about AMI and Boomtown, with people picking up clues and sharing their progress.

Frank, though, has some reservations:

‘Because the app is highlighted as being so important to the narrative this year, and is telling you to go find things – you have to get five scan codes, say – it all becomes more task-driven.’ He also feels that the prominence of the new app has shifted how people behave in the venues: ‘There’s this cult of the snake god storyline – I went into the venue where there was a ceremony for the snake god, and instead of staying part of the ritual, people were chatting about finding codes…’

The ever-present AMI: who’s controlling whom? Photo Andre Pattenden

Interestingly, the fact that Frank is a dedicated video gamer makes him less inclined, rather than more inclined, to appreciate AMI:

‘I love gaming, but I never really liked the whole hunting Pokemon thing. I can see that a lot of people really enjoy integrating real life and gaming, but for me I game because I want an escape from the world; to get as far as possible from it. But that’s just me! I can imagine the performers might want a bigger audience for their piece – and there were a lot more people at all the immersive venues in the districts this year – but for those of us who get that unique, unexpected experience, it is amazing. It’s a bit like in Punchdrunk shows when you’re alone down in the basement and get a unique one-on-one encounter. I don’t think you need to force or over-encourage people to discover the interactive elements.’

That small quibble aside, Frank does feel that Boomtown is the best festival experience out there:

‘Boomtown is like a real place – a town rather than a festival – it has its own life. You feel that you are inside a fantasy – like being in the Truman show! You never know what you’ll discover. That’s the side of things I love….’

Doug (who as well as being artistic director of Invisible Circus and narrative director of Boomtown is also the instigator of the Extinction Rebellion-linked Red Rebel Brigade) reminds us that although it is all a fantasy, and fabulous fun, there is an activist intention: ‘Our aim is always to mirror the real world and question the status quo; the commercial domination and environmental consequences – so using theatre to hold that mirror up to the world’.

For Ciaran, the best thing about being a performer at Boomtown is how playful and generous the audiences are: ‘They will rock up with their own fully-formed characters and will do absolutely anything to get through the narrative, which is such a treat as an immersive actor because you can just react to what they bring you, and every audience member creates a completely new and fresh interaction.’

And really, you can’t ask for anything better than that! A truly ‘total’ theatre experience.

Featured image (top): Boomtown 2019. Photo Rosa Malcolm.

For more on Boomtown Fair, see www.boomtownfair.co.uk

Boomtown Fair Chapter 12: New Beginnings will take place 12–16 August 2020. Tickets are now on sale.

Boomtown have received funding from Arts Council England to further the development of artists and the immersive elements of the festival.

Boomtown’s Town Centre ‘university’, The Ivory Towers Academy, was created by Bath Spa University students, as part of a scheme developing partnerships between Boomtown and several different universities.

Frank Foster-Prior and his friend Emma attended Boomtown Fair: Chapter 11, A Radical City, 7–11 August 2019, as guests of the festival.

Ciaran Hammond is an actor, director and writer – and a regular contributor to Total Theatre Magazine. He has performed at numerous editions of Boomtown Fair.

Doug Francisco is narrative director of Boomtown and creative director of The Invisible Circus. www.dougfrancisco.com

For more on the Red Rebel Brigade www.redrebelbrigade.com

The Invisible Circus are celebrating 20 years of ‘site-specific wonders and acts of creative revolution’. https://invisiblecircus.co.uk/