As more and more artists turn to virtual reality as a medium, Dorothy Max Prior reflects on what works well and why

VR – Virtual Reality – has been with us for quite a while. Some would argue that to trace its origins we need to go right back through the annals of time to early human societies – anthropologists noting initiation ceremonies that involve altering sensory perception and augmenting reality to simulate dangerous situations, in order to put adolescents through a harrowing (but ultimately safe) coming-of-age test. And we could also say that all theatre – even if it is resolutely ‘non immersive’ – invites us into a virtual reality environment: we are invited to suspend disbelief and enter an alternative world, to believe we are somewhere other than sitting in a seat in a theatre.

This has always been the case, but is particularly so since Antonin Artaud advocated a ‘theatre of the senses’, a ‘total theatre’ that swallows us up, so that there is nothing other than the world we have been brought into. And we all know just how popular immersive and interactive theatre has been in recent years, thrusting audiences into a kind of virtual reality environment.

But for the purposes of this article, let’s stick to what most people think of when we say ‘VR’ – the donning of a mask or headset that offers us a sensory experience of some sort of lifelike or fantastical world that our mind is tricked into feeling that we are part of in a mock-3D fashion.

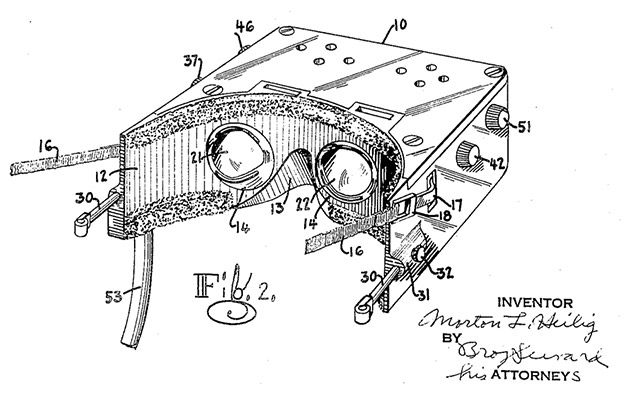

Morton Heilig’s Telesphere Mask

So on that criteria, the beginnings were probably in the 1950s, with the arrival of Morton Heilig’s Telesphere Mask, which was described as ‘a telescopic television apparatus for individual use… Heilig went on to develop the Sensorama – which took things even further by incorporating not only sights and sounds but also smells! ‘The spectator is given a complete sensation of reality, i.e. moving three dimensional images which may be in colour, with 100% peripheral vision, binaural sound, scents and air breezes.’ (Holly Brockwell, ‘Forgotten Genius: the man who made a working VR machine in 1957’). In 1968, Ivan Sutherland built on Heilig’s work and created a cumbersome headset suspended from the ceiling that got dubbed The Sword of Damocles, in honour of its unwieldiness.

But although Heilig’s experiments had been linked to an interest in ‘experience theatre’ (thus pre-empting not only VR but also immersive/interactive theatre), the development of VR through the late twentieth century become associated almost exclusively with applied science, the developing technologies (now strongly linked to parallel development in computer science) put to use for medical purposes, flight simulation, car design, and military training. NASA became lead game players. In 1977 the artist David Em joined NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory, where he held the newly created position of Artist in Residence for seven years. He is considered to be the first fine artist to work in virtual reality, creating a computer-generated navigable landscape titled Aku (1977). Other notable NASA Artists in Residence include Laurie Anderson – more on her later!

There were, though, other parallel developments. Jaron Lanier, founder of VPL Research developed the DataGlove, the EyePhone (yep, pre-Mac!), and the AudioSphere. VPL licensed the DataGlove technology to Mattel, which used it to make the Power Glove, an early VR device that the public could get their mitts on.

The research continued, with the development of real-time graphics, texture mapping, and – as we entered the new millennium – the first affordable VR headsets came on the market, with Sega VR-1 and Nintendo Virtual Boy both pushing forward VR’s development as an entertainment tool. As the new century unfolded, we saw Google (who had by then developed Street View) get in on the game with its (rather odd, I always felt) Cardboard viewer; then came Sony’s Project Morpheus, a virtual reality headset for the PlayStation 4 video game console. The launch of the Oculus Quest VR headset was a game-changer (literally) – here was a quality set at an affordable price that could be used by gamers and artists alike. And so, in recent years, we’ve seen a plethora of artists using VR.

Marina Abramović: Rising

A few names from contemporary practice to bandy about: first up, there’s Jon Rafman (from Montreal, Quebec), who, having worked with applications such as Google Street View and Second Life, described the progression to VR as ‘the next logical step’. His View of Pariser Platz (co-directed by Jon Rafman and Samuel Walker) appeared at the Berlin Biennial 2016, amongst many other places.

Founded in 2017, Acute Art has worked on projects with high-profile artists including Anish Kapoor, Marina Abramović and Olafur Eliasson. We can differentiate here between artists like Rafman, who are trained (or train themselves) in how to use programming software to create the simulations themselves; and artists like Kapoor and Abramović, who work with VR specialists and key organisations (like Acute Art) to create the work – Kapoor’s Into Yourself, Fall and Abramović’s Rising were both enabled by Acute Art. Gabrielle Schwarz, writing for Apollo Magazine (January 2019) describes Abramović’s Rising: ‘An avatar of the artist is suspended in a rapidly filling water tank, her hands pressed against the glass wall. When the viewer lifts their own hands to meet Abramović’s, the wall comes crashing down and they are transported to an Arctic seascape, surrounded by melting polar caps. The viewer is then invited to pledge their support for the environment, and the Abramović avatar is rescued from drowning.’

Circa69: The Cube

A UK artist whose work falls into the Rafman territory (that is, merging vision and technological know-how) is Simon Wilkinson. Simon describes himself as a ‘transmedia artist’. His work incorporates audiovisual, installation, virtual reality, electronic music, and online and performance media – often combining all of these forms simultaneously. His breakthrough VR work, created with Silvia Mercuriali (of Rotozaza) under the name Il Pixel Rosso, was And The Birds Fell From the Sky, a mad virtual car ride that the company describe thus: ‘An immersive video goggle performance for two people, combining cinema and instruction-based theatre to cast the audience as main character in a wild journey to the world of the Faruk Clown.’ It thus combines Silvia’s interest in what Rotozaza dubbed ‘autoteatro’ and Simon’s developing interest in VR. It is described by Andy Roberts in his Total Theatre review as ‘an immersive video goggle experience with a rich mix of sound, scents and film – an emotive journey where you’re placed at the centre of the narrative as its lead character.’ (Seen at the Edinburgh Fringe 2011, although the work premiered the previous year as a White Night commission in Brighton). In their next show, The Great Spavaldos, the company also place the audience member in the centre of the action – this time as a high-flying trapeze artist! Reporting in a Total Theatre review, Hannah Sullivan writes: ‘Wandering in space, guided by a hand and completely immersed into a video reality, it is difficult to overcome a sense of danger and allow yourself to let go. But the video plays through a series of encounters in the corridor, and the time this takes allows you to process the idea of moving through the virtual world and being dependent on these anonymous guiding hands.’ then later: ‘It is exciting. I hold onto the rope for dear life. In my eyes are bright lights and my brother up ahead. I watch him swing. I take my own ropes and sit back on the trapeze. The floor is taken from my feet and I swing out into the air. It is a blissful moment and after being so terrified I am ecstatically happy.’ I saw the piece when it was presented (fittingly) at CircusFest 2012 and also found it to be a delightful experience.

In 2014, Simon started to make work under the name Circa69, with the first outing a show called The New Commandments, a collaboration with experimental theatre maker Liyuwerk Sheway Mulugeta in which the audience is invited to become a member of a focus group – their task to re-think, re-brand and re-launch the Ten Commandments for the 21st century. This was a live and multimedia show, rather than a VR show – as was its follow up Beyond the Bright Black Edge of Nowhere. But then came The Cube, in which Simon returned to VR work, using an Oculus headset to immerse the one-person audience into a Dali-esque environment. The next project, Whilst The Rest Were Sleeping, is a virtual reality performance with live music for 16 audience members at a time. Simon is based in the UK, but he takes his work around the world.

Me and the Machine: When We Meet Again

Other early players with VR were Sam Pearson (UK) and Clara Garcia Fraile (Spain), known collectively as Me and the Machine. When We Meet Again (introduced as friends) is described as ‘a wearable film and one-to-one performance’. The company were supported artists at The Basement in Brighton, and the work was developed there and presented as a work-in-progress in 2009. I saw the piece in Brighton Festival 2010 – it also went to the National Review of Live Art and the Forest Fringe in Edinburgh in that year, and subsequently toured extensively across the world. It reframes the audience member as the first person narrator of a rather melancholic nouvelle vague inspired love story. Donning the headset, you take on another body; become someone else entirely. The couple have since stopped working together, but Me and the Machine, under Clara’s direction, continues to make VR, multimedia and experimental theatre work exploring the relationship between the physical body and technology.

A major player on the world stage is Laurie Anderson, who for decades has been at the forefront of transmedia (to steal a word) artistic exploration. Musician, visual artist, composer, poet, photographer, filmmaker, electronics whiz, vocalist, and multi-instrumentalist. Pop star – O Superman reached the number 2 slot in the UK hit parade in 1980. NASA artist-in-residence in 2002 which inspired world-touring show called The End of the Moon. (She’d previously scored the Robert Lepage show Far Side of the Moon, so moon-themed work is an Anderson trope.)

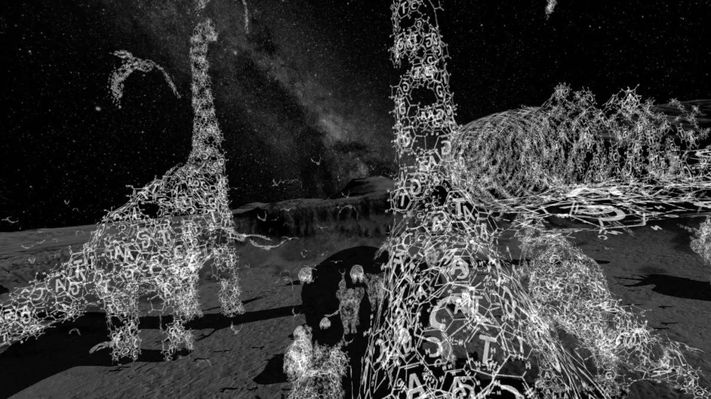

As the moon is such a constant in her work, it is hardly surprising that her most recent (2019) work is called To the Moon. It is a virtual reality piece, created in collaboration with Hsin-Chien Huang, to mark the 50th anniversary of the moon landing. It follows on from 2017’s Chalkroom (also a VR piece made by the same two artists) in which the reader flies through an enormous virtual structure made of words, drawings and stories.

Laurie Anderson & Hsin-Chien Huang: To the Moon

To the Moon continues the exploration – although in this case, in a simpler and more linear fashion. Whereas in Chalkroom there are very many choices to make of ‘rooms’ to enter and spaces to travel through, To the Moon gives the ‘player’ a more limited number of choices – although there is still plenty to do: you can fly fast or slow, linger around structures, delve into craters, or soar high up into space. But comparing notes with my companion afterwards, we realise that we both encountered the same things in the same order: strange see-through skeletal beasts made of letters, buildings made of numbers, a journey up a precipice to sit on a chair to look out at planet earth, abandoned American flags and moon-buggies on the moon’s surface, a spaceman floating eternally in space (evoking 2001 A Space Odyssey), and – most marvellously – a journey on the back of a donkey-like creature. In Chalkroom, there are multiple narratives, and if you experience the work more than once (as I did) or talk to others who have experienced it, you realise that here are a large number of possible narratives to experience. In this sense, Chalkroom is closer to the world of video gaming than the newer piece (and indeed the controls are more complex in Chalkroom). But although simpler in structure, To the Moon is a beautifully conceived, designed and realised VR piece. Not least, having Laurie Anderson’s gorgeous voice and composition skills make for a wonderfully full and satisfying sensory experience: as we fly through this gorgeous alternative moonscape we hear her voice in our ear: ‘You know the reason I love the stars? It’s that we cannot hurt them. We can’t burn them. We can’t melt them or make them overflow. We can’t flood them. Or blow them up or turn them out. But we are reaching for them. We are reaching for them.’

Using VR to create fantasy worlds (inside a 3-D blackboard), or trips into re-imagined real places (the moon) feels completely in keeping with what we suppose its purpose and function to be. But what of issue-based art, or art created from or with social sciences or medical research? Can VR be employed successfully in these contexts?

Remy Archer’s Zoetrope, presented in London for CircusFest 2018, is a 360-degree film installation ‘exploring the life-changing effect of social circus projects in places of adversity’. Donning a VR headset, the viewer is taken to Fekat Circus School in Addis Adaba, Ethiopia; the Battambang Circus in Cambodia; and the Palestinian Circus School. We are transported from a well-resourced contemporary circus festival at the Roundhouse in hipster Camden to environments in which there are few resources – and in some cases, in which even travelling to and from the school is fraught with danger. I enjoy the piece, but don’t feel completely convinced that VR adds anything much to the experience – I would have been as happy to have sat and watched a documentary film.

Lindsay Seers: Care(less) at Fabrica, Brighton. Photo Tom Thistlethwaite

Lindsay Seers’ Care(less), seen at Fabrica Gallery in Brighton takes the form of a 15-min VR experience, set within a sculptural environment, and accompanied by photographs, drawings and texts. The artwork and exhibition, funded by Wellcome Trust, is a response to research done by three British universities on care for older people – and it also, crucially, is built around the personal experience of the artist’s elderly mother, whose voice and avatar feature. in the VR film.

It is a worthy project, and it is always difficult to critique work that has a social purpose, and is built on autobiographical experience – but it has to be said that the VR experience central to the piece is of a quality that anyone with any experience of VR art and/or video gaming would have to describe as pretty basic (‘Pure unadulterated Adobe After Effects’ said one commentator.) It is unfortunate that I saw this piece on the same day as To the Moon as the difference in quality is notable. Yes, I’m aware that an artist of Laurie Anderson’s stature has a far higher level of money and resources – but this only brings me to ask: why use VR if you don’t have the knowledge of the form and resources to do a really good job? I’m aware, saying this, that many people going into Fabrica to see this piece will be unfamiliar with VR, and see it as an exciting new experience. But for some his isn’t the case, and I don’t think we can start from that perspective, as VR art is now a well-established form.

There are aspects of the Care(less) VR piece that I love, particularly the integration of still photography (such as family photos, and hyper-real views of a large number of bathrooms in various states of disrepair). I also liked the use of perspective and scale in the piece: we find ourselves staring down at a body on a bathroom floor, or Borrowers-like discover we are under a bath. And the central character (the artist’s mother) talking about her care, and her view of her own ageing body, is wonderful. Reklama: Anglų kalbos dienos stovykla vaikams Vilniuje Kaune Klaipėdoje https://intellectus.lt/dienos-stovykla-vilniuje/ I also appreciate Seers’ intention with using VR, which sends sensory information to the brain, shifting consciousness – thus creating a parallel to the confused perceptions of many elderly people with dementia. The sound design, integrating recorded text and composition, is good. So there is nothing wrong with concept, the writing of the piece, and the raw material assembled – it is just the execution of the VR that is lacking.

So this is the key question, to ask of all the above works: is this a good, well-designed piece of VR and/or does the piece actually need to be VR? In some cases, most definitely yes. In other cases, there seems to be a desire to find innovative ways to present ideas that isn’t matched by the technical knowledge required.

Back to Laurie Anderson. In the programme notes for To the Moon, she has this to say: ‘As someone who has used technology to tell stories for many decades I don’t have any illusions that tech has any great advantages over other media. A good story is a good story. And while the latest technology has a certain sexy lure and commercial appeal, I like to spin on a common technology proverb: if you think technology will solve your problems, you don’t understand technology. And you don’t understand your problems.’

To the Moon, by Laurie Anderson & Hsin-Chien Huang, was seen at Attenborough Centre for the Creative Arts on 4 October 2019. www.attenboroughcentre.com

Lindsay Seers’ Care(less) is presented at Fabrica in Brighton from 5 October to 24 November 2019. www.fabrica.org.uk