Total Theatre Network are delighted to announce today the shortlist for the Total Theatre Awards 2019. From the list announced today, a total of seven awards will be awarded across five categories: “Physical & Visual Theatre”; “Innovation, Experimentation & Playing with Form”; “Emerging”; “Circus”; and “Dance” at a ceremony to be held on 23rd August.

Following a shortlisting meeting on 14 August, a total of 27 productions from 8 countries have been selected as the 2019 Shortlist for the Awards across the five categories outlined above.

The Total Theatre Awards are a peer-to-peer assessment process of dialogue and debate to recognise excellence and artists pushing the boundaries of independent performance. In order to produce this shortlist, a total of 403 eligible shows have been assessed over the first 11 days of the Edinburgh Festival Fringe. These shows have been viewed between two and four times by a curated panel of 26 peer assessors, comprising artists, producers, programmers, curators, critics and academics, alongside a number of senior industry supporters and advisors. Meeting every two days, the Total Theatre Awards Producing and Assessment team have engaged in 36 hours of collective discussion of all eligible productions in depth, across specialism and across discipline.

Following the shortlisting process, the selected shows will now move to a judging panel where shows are seen by leading arts industry figures including critics, academics, artists and programmers. Seven awards will be given across five categories and the judging panel will announce their decisions at an awards ceremony on Friday 23 August. The judges for the Total Theatre Awards reserve the right to award further productions that open at the festival after the shortlisting has taken place.

The full shortlist for the 2019 Total Theatre Awards is below:

Shows by an Emerging Company / Artist

This Award is supported by Theatre Deli

Burgerz by Travis Alabanza

Hackney Showroom (England)

Traverse

Life is No Laughing Matter

Demi Nandhra (England)

Summerhall

Sex Education

Harry Clayton-Wright (England)

Summerhall

STYX

Second Body (England)

Zoo

YUCK Circus

Underbelly and YUCK Circus (Australia)

Underbelly

Total Theatre & Jacksons Lane Award for Circus

Contra

Laura Murphy (England)

Summerhall

Jelly or Jam

Ampersand (Australia)

Underbelly

Knot

Nikki & JD / Jacksons Lane (England)

Assembly

Raven

Chamaleon Productions in association with Aurora Nova (Germany)

Assembly

Super Sunday

Underbelly and Race Horse Company (Finland)

Underbelly

Staged

Circumference (England)

Zoo

Total Theatre & The Place Award for Dance

Ensemble

Robbie Synge and Lucy Boyes (Scotland)

Dance Base

For now we see through a mirror, darkly

Ultimate Dancer (Scotland)

Greenside

Seeking Unicorns

Chiara Bersani / Associazione Culturale Corpoceleste (Italy)

Dance Base

Six Feet, Three Shoes

Slanjayvah Danza (Scotland)

Dance Base

Steve Reich Project

Isabella Soupart / MP4 Quartet (Belgium)

Dance Base

Total Theatre & Theatre in Mill Award for Innovation, Experimentation & Playing with Form

&

Total Theatre & Rose Bruford College Award for Innovation, Experimentation & Playing with Form

Are we not drawn onward to new erA – Ontroerend Goed

Theatre Royal Plymouth, Vooruit, Richard Jordan Productions, BiB with Zoo

Zoo (Belgium)

Below the Blanket

Cryptic (Scotland)

Royal Botanic Garden Edinburgh

Frankenstein: How to Make a Monster

Battersea Arts Centre and BAC Beatbox Academy (England)

Traverse

Louder Is Not Always Clearer

Mr and Mrs Clark featuring Jonny Costen (Wales)

Summerhall

Nightclubbing

Rachael Young

Summerhall

The Canary and the Crow

Daniel Ward and Middle Child (England)

ROUNDABOUT@ Summerhall

The Accident Did Not Take Place

YESYESNONO (England)

Pleasance

Tricky Second Album

In Bed with My Brother (England)

Pleasance

Total Theatre & Cambridge Junction Award for Physical / Visual Theatre

Die! Die! Die! Old People Die!

Ridiculusmus (England)

Summerhall

Limb(e)s

Ci Co (Canada)

Assembly

Working On My Night Moves

Julia Croft and Nisha Madhan with Zanetti Productions (New Zealand)

Summerhall

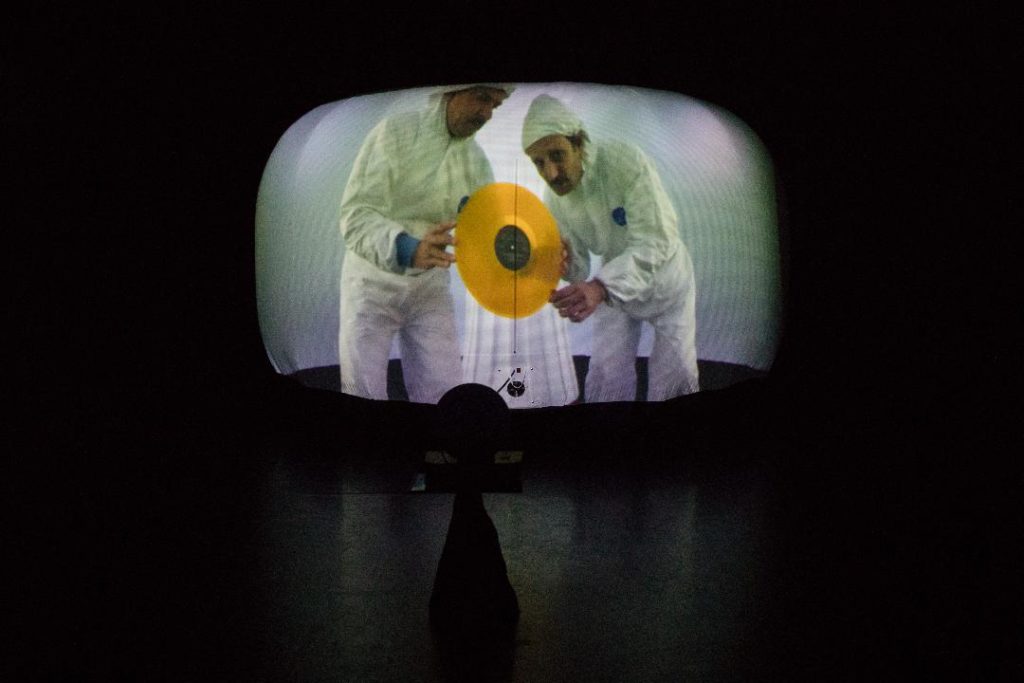

Featured image (top) FK Alexander, previous Total Theatre Award winner, and an assessor at the Awards 2019.

Please note Total Theatre Awards and Total Theatre Network operate independently to Total Theatre Magazine. See https://www.totaltheatrenetwork.org/

Jo Crowley, Co-Director: +44 (0)7843 274 684 / crowley.jo@gmail.com

Becki Haines, Co-Director: +44 (0)7732 818401/ haines.becki@gmail.com

Total Theatre Awards: totaltheatrewards@gmail.com