Beauty, Morality, Ageing, Power…

Theatre elder Dorothy Max Prior, young reporter/performer Ciaran Hammond, and – placed somewhere between those two – artist and writer Zoe Czavda Redo offer a three-way reflection on Gob Squad’s Creation (Pictures for Dorian)

‘It is the spectator, and not life, that art really mirrors.’ Oscar Wilde, The Picture of Dorian Gray

Dorothy Max Prior writes:

We have two days rehearsal. Two days! How is this going to work? This is a big show, in every sense of the word: a highly-regarded international company premiering a new work at the Brighton Festival; a cast of nine performers, three from Gob Squad plus six ‘local performers’; a whole load of kit, from large wheelie mirrors and revolving turntables to roving cameras trailing treacherous cables. Trust, we have to trust.

On day one, while the production manager Chris Umney, tour manager Mat Hand and the technical team of the Attenborough Centre for Creative Arts (ACCA) do the get-in, we are down below in a small rehearsal studio. ‘Imagine,’ says Gob Squad-er Bastian Trost, as we three older performers step forward to to lip-synch to Dalbello’s kitsch hit The Sins of Dorian, ‘that this is where you’ll stand, behind a large mirror, but the space will be twice this depth…’ Hmmm, I’m trying my best.

Gob Squad Creation: Brighton cast

Some of us took part in the R&D stage of the process in late 2017, so have had a brief involvement in the devising process, and have gleaned some sense of the themes and intentions of the piece. Areas of investigation include: the nature and purpose of art; being on display; the human body as art object / a site of artworks; how we ‘frame’ what we see; self-image and identity; and – of course – ageing and how we deal with our ageing bodies. The guest performers are three older people (me plus two) who have spent a life onstage, known collectively as ‘the Roses’, and three younger people who aspire to a life onstage, called ‘the Daisies’. Gob Squad are also people who have decided to spend their professional lives being looked at onstage – currently mid-career and mid-life, average age 48.

Of the Gob Squad team here in Brighton, Simon Will and Berit Stumpf (and Bastian, who is off-stage this time round, acting as outside eye – there is no director) performed the show when it premiered in Berlin, but not Johanna Freiburg, who I’m mostly teamed with in this version of the show. We’re learning together, she says. In one scene, we three Roses are each behind a mirror, responding wordlessly to questions from Johanna such as ‘show me the face of someone who knows they are beautiful’ and ‘show me where the shame is’. The questions vary each time we run the scene – to keep us on our toes; to discourage us from learning a fixed choreography – but the final one is always the same: ‘show me the smile you had as a child,’ which segues into the cue for the next scene, ‘Max, do you still have that same smile?’. As Johanna and I face each other through the mirror, hugging it as one might hug a tree, I am pulled across the stage in a weird kind of waltz, each revolve of the mirror accompanied by a question inviting me to reveal personal details about identity, performance and the journey through life. Being born female in the 1950s, a tomboy childhood, finding my inner femme, working as a cabaret dancer, playing drums in the punk and post-punk years, mothering three boys… the conversation isn’t scripted, and the scene changes playfully each time we do it. Regardless of what decade we are in, it ends when one of the Daisies runs on with a shout of ‘Look At Me!’ countered with a Rose’s response of ‘Do You Know Who I Am?’

Two days on, we are running the show for the first time on the stage. It’s the dress rehearsal, and just hours before the premiere. I get through the run without tripping over any of the plinths, falling off a trolley, missing my light, forgetting the song, or being run over by a waltzing mirror. Hurrah! Because the Roses and the Daisies have been rehearsing scenes in separate rooms, I’m seeing some parts of the show for the first time in this dress run.

Gob Squad: Creation. UK premiere at ACCA, Brighton Festival 2018

Wow, it all works! The mix of a fiercely choreographed movement of people and objects around the stage combined with the relative spontaneity of guest performers’ verbal and physical responses to instructions or questions is a good balance of fixed order and improvisation. The power and humour of the Gob Squad performers’ conversational exchanges and monologues is a revelation – we’d seen so little of this in rehearsal, partly because they’d held back, to keep the show as fresh as possible, and partly because the rehearsal period for the guest performers was so short that the focus was on our scenes and cues.

So now, a couple of hours later, we are back in our starting positions, Daisies and Roses sitting out of sight in the wings on a row of chairs stage-right. Johanna is at the back of the stage creating a flower arrangement. Ah no, sorry – it’s not mere flower arrangement, it’s Ikebana, a Japanese artform in which nature and humanity are brought together, the Ikebana Master creating displays that emphasise shape, line, and form. We hear the chatter of the audience, which gradually subsides as Simon, practicing his life-drawing skills, riffs with Johanna on the power of triangles in general, and the relationship between (A) artist, (B) object and (C) viewer in particular. Johanna is ruthlessly trimming all the leaves from a stalk, saying that she is helping the flower to be seen, improving on nature, because ‘being natural is simply a pose, and the most irritating pose I know.’ Oh yes, says Simon, five minutes in and we get our first Oscar Wilde quote! ‘I think this really needs a frame’ says Biarit, holding a gaudy gilt frame in front of Johanna’s flower arrangement, the image now projected onto a giant screen behind them – a frame within a frame. ‘This is all very well, but I feel I need to work with a different sort of material, something more like this…’ says Biarit. And she walks over to where we are sitting, takes my hand, and we’re off, into the limelight, seeking the gaze.

A wish come true

A fantasy revealed

By mirrors of the mind

Reflecting pictures of the soul…

Gob Squad: Creation. UK premiere at ACCA, Brighton Festival 2018

‘Experience is simply the name men give to their mistakes…’

Zoe Czavda Redo writes:

There’s a palpable frisson at ACCA tonight. I daresay all the theatre-makers in town are here, the older ones with spare cash in hand for the post-show debrief in the bar, the young ones making notes for their college papers. Gob Squad, the performance collective who (someone is whispering, someone else is writing) formed as university pals in Nottingham in the 90s and have been based in Germany since, come to the UK every so often as a refreshing easterly wind, ambassadors of a Berlin ‘air’ long after it was sold in bottles but before the birth of maybe a third of the audience. Their use of – ‘irreverent!’ ‘contemporary!’– conventions (such as live camera feeds, unusual locations, and the mixing of professional and non-professional performers) is 25 years on, and now absorbed into the canon; the company trades freshness for mastery, and their latest show is – in part quite literally – a reflection on this. A controlled, sprawling, moving, and beautiful piece using mirrors, frames, plinths, humans older and younger, and flowers wilting live under a heat-lamp, brings Gob Squad’s own midlife crisis, the inter-generational encounter it provokes, and all the ensuing questions of freshness, liveness, ageing and self-regard to the stage.

Creation (Pictures for Dorian) uses The Portrait of Dorian Gray less as a template, more as a palate; it’s more remix than reprise. In Wilde’s novel, famously, Dorian sells his soul to live a devil-may-care life while a magical portrait confined to the attic ages in his stead. Gob Squad plays with the Victorian vocabulary of flowers – star of the still-life – and portraiture, a means of preservation and archiving, in tension with artistic expression. As an accumulationist piss-take on the artistic process, as well as a poignant meditation on mortality, this piece feels messier and grander when it’s happening than its constituent elements would suggest.

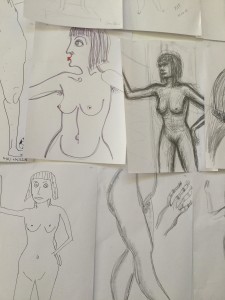

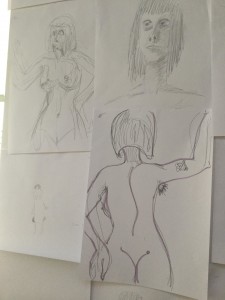

It starts with an almost-bare stage, a single performer bantering with the audience, and adds elements gradually, starting with flower arrangement and extending the principles of Ikebana to the ‘locally sourced material’: three performers in their 20s and three in their 60s, at first compliant models to be directed and manipulated into works of art using frames and plinths, and the roving camera. The local material is not ‘raw’, exactly; all are professional performers (emerging or veteran) and used to being onstage and being looked at, a suspicion confirmed as they go past being arranged by the ‘artists’, and begin to offer narratives and perspectives, hopes and reminiscences of their own: a young girl reclaims her narrative on Instagram; the athletic Adonis creates movement sequences Biarit struggles to follow; an aged ex-dancer performs a version of the choreography that represents the pinnacle of his life onstage. Conversation seems unscripted, movement highly orchestrated. Performers, frames, mirrors, plinths, cameras – all seem to be gliding around the stage to rephrase themselves. Costumes are traded and exchanged, from Grecian sheet-robes to fantasy-futurist metallic getup; bodies create and invert relationships amongst each other by moving in and out of frame, behind and in front of mirrors.

Gob Squad’s pacing and deadpan humour work well in the weave of this live video; the stage itself is a mixture of behind the scenes and outside-the-frame, a shifting series of small scenes-as-bouquets, continually melting towards, or rearranging, into something else. As expanded ikebana, it’s all happening before us, all under the light, and yet in the spaces where we aren’t looking, a sort of transformative magic seems to have taken place. We leave the auditorium softened and devastated. No one goes to the bar right away.

Gob Squad: Creation. A London Rose and a London Daisy prepare

‘Be yourself, everyone else is already taken.’

Ciaran Hammond writes:

Southbank Centre’s Purcell Room: Sharon Smith stands at the back of the stage. She’s pruning a selection of flowers and arranging them on a table. ‘Ikebana’ she tells us. Co-performer Sean Patten draws a crude caricature of an audience member. Sharon tells Sean and the audience that Ikebana is a meditative practice that requires the person to appreciate each flower for what it is, and to avoid comparison and establishing any sort of hierarchy between the flowers. It is about the composition as a whole. These ideas, and others, surrounding Ikebana open up a conversation for exploring identity.

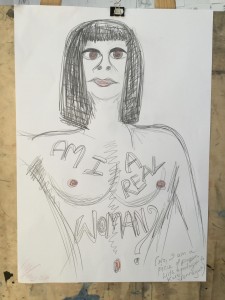

In exasperation with the flowers, the third Gob Squad performer, Bastian Trost, brings on six guest performers claiming he needs ‘A different sort of material to work with’, directing and positioning them on stage among potted plants, giant empty photo frames, mirrors and a camera – the live footage of which is projected onto the back wall of the stage. Three of the guest performers are in their late teens or early twenties, and the other three are in their late sixties and seventies. In the middle, we have Gob Squad. In the same manner that Sharon places trimmed twigs next to one another, the exposed and vulnerable guest performers are lined up, moved around and framed as art objects. Wearing skin-tight, pale body suits and hair nets, they are stripped down to their most basic and least defined; trimmed of unnecessary foliage. After bringing their guests back to a tabula rasa, Gob Squad use themselves and the guest performers to ‘find art’ by delving into what makes each performer who they are.

The piece explores both the core Gob Squad performers’ and the guest performers’ lives and personal traits through its autobiographical angle and distinctive non-actorly performance style. For a young man studying acting at Lancaster Uni, this is his first time on a stage in London. For a seasoned drag performer… well, he’s lost count. The guest performers are given brief introductions and are provided with tasks to complete throughout the performance, such as walking towards the camera ‘with the spirit of nature’ and being asked questions like ‘do you want to die on stage?’ and ‘what were the 70s like?’ The tasks and questions are designed to bring out a specific aspect of each performer, and are tailored to each performer with a level of specificity that significantly changes the piece depending on who the performers are. The performance’s structure and core ideas remain the same but its content changes drastically in each new incarnation. What holds the piece together, and keeps its identity intact throughout its different iterations, is the company’s core practice, as well as the ideas it explores: Gob Squad at this point in their careers have become well cemented in the postmodern performance landscape, often incorporating multimedia technology and a non-performative style into their shows. Their creative process is solid, and is framed within Creation as a living, breathing thing that is explored within the piece, in some ways as equally as the guest performers are explored.

The ideas that Creation explores have depth, are well developed and are open for interpretation within the performance, but due to the piece’s reshaping between iterations it is suspected that the process of essentially making a different – but quasi-identical – performance for each location has inhibited the performance’s development in more physical and technical areas. The performance feels unintentionally slow with the crescendos in energy, although well placed, feeling as though they are being walked through, lacking in an organic quality. This strips some parts of the performance of its sense of autobiographical truth and its non-performative nature. At times when the rehearsed parts of Creation stick out for what they are, the question of whether they’re rehearsed or improvised no longer exists for the audience and the performance loses a sense of mystery. This loss, at times, hinders the audience’s engagement with the performance and makes certain aspects of the piece feel disingenuous. When we can see the confessions of a performer as rehearsed, what they’re saying becomes merely another part of the performance, rather than a part of them and their identity.

The ambiguity and openness within the way Creation presents and theatricalises its performers makes them more alive on stage; what gives them strength as individuals, in the audience’s eyes, isn’t a rigid and easily attainable categorisation of their personalities, making them easier to comprehend. Instead, Creation shows constantly changing individuals, who with each movement on stage, become infinitely more complex, and is a soft reminder of perhaps how is best to observe our guest performers, and others, on and off stage.

Gob Squad: Creation, London premiere at LIFT

‘The truth is rarely pure and never simple.’

Dorothy Max Prior writes:

I’m here to see how the show looks from the outside – but of course it is not the show I was in. Another time, another place, another show – performed by nine different people. For not only do the local guest performers change with each location, the core Gob Squad team changes too. Bastian, outside eye in Brighton, has taken Biarit’s role for the London LIFT shows. Sean Patten has replaced Simon Will as principal narrator and muser on conceptual conundrums. Sharon Smith has replaced Johanna Freiburg as Ikebana arranger and I’ll Be Your Mirror reflector on the naked female form onstage (although apparently it is Sarah Thom in this role in some of the London shows).

The form and structure is essentially the same – the order of the scenes, the mechanics of moving people and objects around, the live-feed video, the clever way of signifying a scene has ended once the artwork being created live has been named (the name, often an Oscar Wilde quote, scrolling up over the image on the enormous back-wall screen), and the central notion of having nine performers who represent a life on stage, past present and future. But the content feels radically different.

Of course, it goes without saying that I will feel forever wedded to the version of the show I took part in, and can never offer an objective view of Creation, but I will try my darnedest to bear witness in a fair and honest way to what is being offered here on the stage at the Southbank Centre’s Purcell Room.

A stage, I will say first of all, that seems a little small for all the things that are happening on it, particularly when all nine performers are onstage together, moving in and out of various groupings. I’m thinking particularly of a scene later in the piece in which all perform an ensemble score of repeated gestures, presented forward-looking to the audience ( if ‘yes’) and backward-looking to the mirrors (if ‘no’). From the third row, many of the performers feel a little too close to us for this epic, panoramic picture to really work. Was it thus in Brighton? I was on the other side of the footlights then, so can’t say – but I know that the Attenborough Centre has a particularly wide and deep stage, so perhaps not…

On the other hand, some of the more intimate scenes are truly breathtaking. Particularly, a three-way conversation between Bastian, a Daisy (‘Can I call you my past?’) and a Rose (‘Can I call you my future?). The combination of performers, and the particular content of this version of this scene is a beautiful thing. All three identify as gay, and a genuine echo-chamber is set up in which we clearly see, in an eternally reflecting triptych, the past, present and future of queer politics and performance, with Bloolips co-founder Stuart Feather’s revelations of the pioneering days of drag performance bringing a hushed awe to the auditorium.

It is also interesting to see how the different Gob Squad performers bring a completely different energy to the show. The strongest contrast is between Johanna Freiburg (Brighton) and Sharon Smith (London). For example, in the scene in which the nine performers stand in a straight line at the front of the stage, facing out, the audience invited to feast their eyes on this collection of humans who live to be looked at. As performers and audience silently mirror each other’s gazes, a woman performer removes her clothes as she returns the audience’s gaze. When that woman is Johanna, her cool, calm pose and unflinching gaze undoes the spectator, and there is a stunned silence finally broken by laughter when Johanna says, ‘They are all looking at me, you can go now.’ When it’s Sharon, there is a cheery throw-away attitude that makes for a more obviously humorous, less unnerving moment. The waltzing mirror scene also has a very different energy in this version: where Johanna and I stood nose-to-nose on either side of the mirror, arms outstretched in an embrace of mirror and each other, engaged in an intense, one-on-one conversation delivered with little regard to the audience, Sharon and guest performer Claudia Bolton (a former member of legendary 1970s women’s theatre group Beryl and the Perils) take the mirror in a one-hand grasp on either side, questions and answers swinging out to the audience with many a nod and humorous aside. Often, in this version of the show, there are winks to the audience and a feeling of knowingness that was pushed far less in the Brighton incarnation. I am sure that every incarnation of the show acquires its own special feel and form – it’s a piece that you could see again and again.

There are moments when some of the guest performers seem to have their responses over-prepared. This may be the inevitable result of this being day four of their run – familiarity has set in, and there might well be less spontaneity than on day one. Perhaps we similarly settled in too much as our Brighton run progressed – and I now completely understand why Johanna said to me, in response to a worried question about a cue, ‘I may well change what I ask you every night.’ I’m reminded of the old performance adage ‘no acting required’.

What I really get on the outside of this extraordinary piece of work is the sheer beauty of the show. Such utterly gorgeous stage pictures drawn and erased! From the auditorium rather than the wings, I can far better see the cleverness of the interplay of live and mediated image. And I adore witnessing the obvious rapport and complicity between the God Squad core team. I enjoy the way that every element of the show – costume, set, lighting, sound, performance – works harmoniously together, creating (yes!) an Ikebana arrangement in which balance and harmony is all.

Mostly, I appreciate being asked to think about what I am seeing. Where is the balance between objective and subjective viewpoint? Who am I watching most and why? Why am I drawn to one image and away from another? Who determines what is ‘good’ art, or even what is ‘art’.

Reflecting on both experiences, inside and outside of Creation, I ask myself: why do any of us crave the eye of the beholder? Is the present moment always our greatest moment? Am I happier to be (A) artist or (C) witness? I certainly enjoyed being (B) art object, relieved of the obligation to think too hard, try too hard, or take too much responsibility for the success of the show.

I’m in my mid-sixties now. It is probably true to say that there is more behind me than in front, onstage and offstage. How did I survive? Have I any regrets? I’m certainly closer to my death than to my birth. What will remain of me after I die? Does it matter? What will people do with all my belongings when I’m gone? And what about that painting in the attic – will they chuck it out with the rest of the clutter?

Though dreams may fade

The images remain

They find a secret place

To hide the terror and the pain

of Dorian

The Sins of Dorian…

Gob Squad: Creation (Pictures for Dorian)

All images courtesy of Gob Squad.

Quotes by Oscar Wilde. Song lyrics by Dalbello.

Gob Squad: Creation (Pictures for Dorian):

Concept and direction: Gob Squad (Johanna Freiburg, Sean Patten, Sharon Smith, Berit Stumf, Sarah Thom, Bastian Trost, Simon Will)

Guest performers (Brighton): CHUB RUB, Holly Nomafu, Sam Longville, Dorothy Max Prior, Kate Dyson, Nicholas Minns

Guest performers (London): Claudia Bolton, Christina Brown, Lieve Carchon, Stuart Feather, Mike Narouei, Amelie Roch

The UK premiere of Creation (Pictures for Dorian) was presented at the Attenborough Centre for Creative Arts (ACCA) 23–27 May 2018 as part of the Brighton Festival. It was seen by Zoe Czavda Redo on 24 May 2018.

The London premiere was presented at the Southbank Centre’s Purcell Room 4–7 June 2018 as part of LIFT. It was seen by Dorothy Max Prior and Ciaran Hammond on 7 June 2018.