Buenos dias! Total Theatre Magazine is in Mexico, taking part in FiCHo, a festival of circus, clown and physical theatre, which stretches across the sunny city of Guadalajara for ten days in November (then steps out to other parts of the country).

Your trusty editor was invited to take part wearing a number of sombreros – workshop leader, cabaret artist and community performer, and facilitator of critical writing workshops. And it is this last that is the subject of this post…

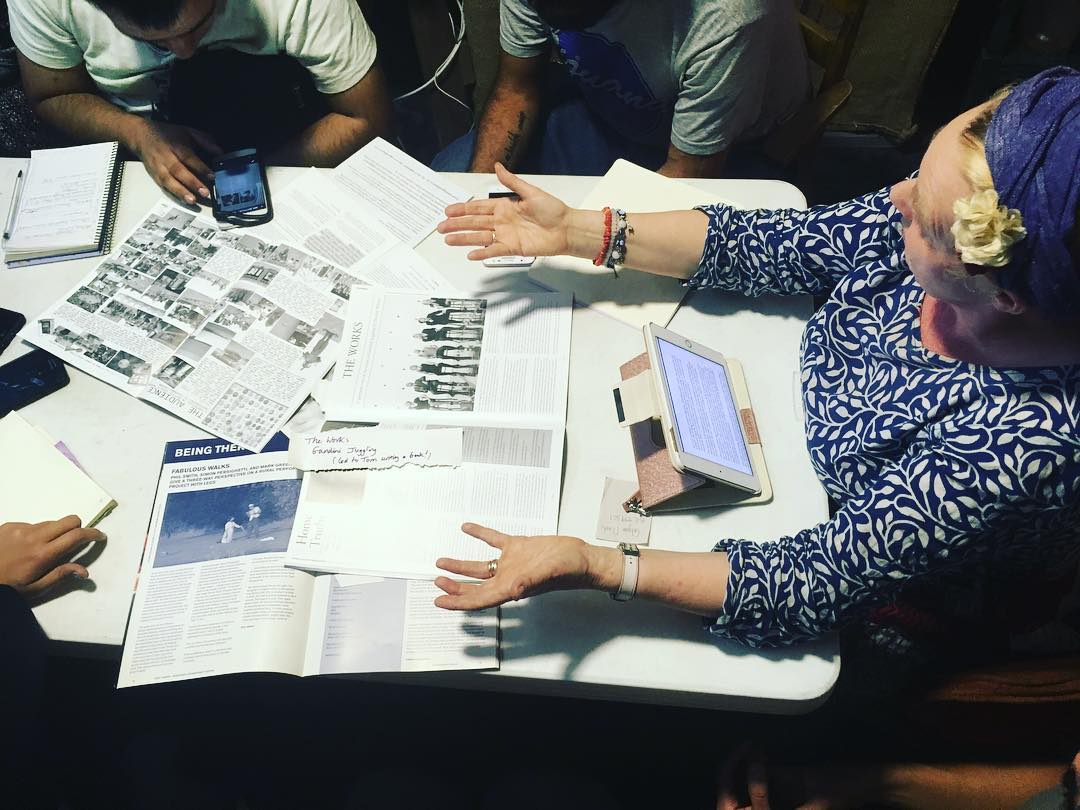

The 20-strong writers’ forum gathered by the festival includes established journalists and critics, young writers, circus artists, poets, short fiction writers and lyricists. The intention is to look at not only the conventions of arts journalism (the usual reviews, interviews and artist profiles or puffs) but also at ways in which text of any sort – tweets, poems, fiction, essays, long-form magazine articles, raps and rhymes, bon mots scrawled on post-it notes – can interact with live performance, creating an intertextuality of creativity.

In my opening talk, I used a batch of Total Theatre print mags (oh blessed artefacts, how we miss you!) as a springboard to discuss such things as:

The importance of writing about performing arts: Who is the writing for? How and why do we write about performance? We talked about different outlets for critical writing: the local newspaper, the specialist arts press, the proliferation of blogs and online magazines. We discussed Total Theatre’s founding principle of existing mostly for the artists and the arts industry, whilst acknowledging that the general theatre audience have to be considered too, as they might not have bought the print magazine, but certainly read the online magazine, particularly at peak times , such as during the Edinburgh Fringe.)

What other roles are possible, other than professional critic? For example, artists writing about their own work, or writing about other artists’ work. (Plenty of examples in Total Theatre of this, including the time Theatre Ad Infinitum’s co-directors, Nir Paldi and George Mann, interviewed each other.)

We also looked at how to give constructive criticism and helpful feedback when writing about performance; and the notion of the ‘creative response’: ways to respond to live performance that are beyond the usual critical writing format. (I cited some examples in TT that included the time we commissioned a visual artist to draw their response to a Pina Bausch show; and street arts and clown photoessays.)

But I particularly wanted to think and talk about how best we write about performance work that is non-text-based and is predominantly physical and visual: contemporary circus; mime, clown & physical theatre; visual arts performance, live art and installation. The stuff that has been at the heart of Total Theatre’s work for these past 30+ years, in other words.

Total Theatre has always been an artist-led project. We have pioneered the practice of artists writing about their own work, through creation or rehearsal diaries, reflections, our reworked interview format Voices, and multi-voiced review formats such as the Being There series (alongside more traditional formats such as regular reviews, company profiles and interviews).

We have always, in our reviews and in feature-reviews such as The Works, or in observational ‘outside eye’ reports on the creation process, championed critical writing that aims to understand and support the work artists have made, finding ways to both document and to offer constructive rather than destructive criticism. This I feel is a vital point: our maxim is: how can our writing HELP artists on their chosen path, not hinder them!

For many people who write for performance, writing about performance makes for a great counter-balance. It is good to learn how to witness your own work, through keeping an artist diary, or writing a critical evaluation of your own project, or an artists’s blog; and it is good as an artist to learn to write, critically and kindly, about other artists. Having multiple roles and perspectives can be a positive thing. As someone who does both – writing for performance, and writing about performance – I feel that the two can sit very happily side-by-side. I don’t actually feel that the skills are that different. All writing – be it journalism, prose fiction, poetry, drama – is based on and grows out of observation of the world. An ability to witness, report, notice, engage… To really see and hear what is out there. All good writing is the same in that it speaks of human life truthfully.

I feel that the main role of a reviewer is not to be a fireball of opinion, but to be a good witness. The good witness asks: what did I see/hear/feel/understand? What was given to me, and how did I receive it? How did it make me feel? What thoughts do I have about it that go beyond ‘oh I liked it’ or ‘oh I didn’t like it’. Just to have a reliable, non-judgemental witness who is there to try to understand and appreciate, there with an open heart and mind, can be fantastic for the artist who is presenting the work: to place work out there, and have it truly SEEN and HEARD and ACKNOWLEDGED is fantastic!

This type of writing about performance has much in common with the dramaturg or the ‘outside eye’. I feel that if I am invited to see a show (whether as critic or outside eye), my job is to try to get under the skin of the work, to give constructive criticism and helpful feedback.

It is also very important for physical/visual theatre and circus to be written about because if there is little or no spoken word in the show, there is probably no written play-script. Live performance is an ephemeral artform, it exists in the moment and then it is gone, so it needs to be written about, so that others (here and now, or in the future) can learn about it and have some sense of the work, even if they weren’t there. A few shaky photographs is not enough – and anyway, the written word is a technology that will survive. How do we know about non-text-based performance from 50 or 100 years ago? We know from witness accounts. So writing about performance is a form of documenting work; creating an ongoing, living archive.

Inevitably, in our opening session, we went on to discuss a question often posed by regular theatre critics: How exactly do we write about performance work that is non-text-based and is predominantly physical and visual? (i.e. forms such as contemporary circus; mime, clown & physical theatre; visual arts performance, live art & installation.)

Developing our ability to witness is vital here! If there is no spoken text to understand and report back on, no written play text to consult, then we must develop our skill in truly SEEING the visual pictures presented, and reflecting on visual imagery and association. We can develop these skills through repeatedly seeing as much work as possible – and by going to see painting, photography, installation work and other visual forms to teach ourselves to look, really look, at what is in front of our eyes. The more we see, the more we learn. Look at the way children look at things, really look. At leaves, at dogs, at the sky, at people. We honed our observation skills as children, but often then forgot that these skills need to be kept fresh.

And it had to be said too that you don’t need to ‘understand’ everything! Visual images are complex, multi-layered, often operating on a subconscious level, evoking what Artaud called ‘the truthful precipitates of dreams’ – it is not your role as the writer/reporter to explain everything – you can just say what you saw and heard, and how it made you feel. Write from your heart as much as from your head.

Other sessions in the week of roundtable workshops included a performative intervention by poet Miguel Asa who talked of butterflies and beards, in a reflection on the inter-relationship between reality, dreams, memories, and imagination, and issued us with stickers saying ‘Por favor lea a poesia’ (Please, read poetry), a directive I’ve also seen stencilled on the streets of Guadalajara. Established Mexican critic Ivån Gonzålez Vega presented a talk in which he posited the view of the critic as the eye of the audience. FiCHO hosts Cabaret Capricho ran a humorous performance-lecture on circus equipment and terminology (fear of not knowing what things are called often stops theatre critics writing about circus). Later in the week, I ran some creative writing exercises focusing on first-person reminiscence of early memories of circus (these then crafted into prose pieces, essays or poems), and we worked in pairs on interviewing skills.

As FiCHo Festival launched, so to did the writers’ forum blog, Textear el Circo. There was also a plethora of post-its at the first weekend of performances, including one-word audience responses to the shows, and a whole swathe of posts on social media with the hashtags #textearelcirco and #FichoFest

The message is: whether you choose to write in the conventional review format, use instant response media such as Twitter or Facebook, or forge a creative response to what you’ve witnessed in the form of a haiku, song, poem or short story – get out there, see work, get writing. Por favor.

Dorothy Max Prior is a guest of FiCHo Festival, which takes place in Guadalajara and other cities in the state of Jalisco, Mexico, November 2017.

See www.fichofest.com for the full programme of shows, events, talks and interventions.