And the story so far?

The Fringe started quietly. The first few days of previews and openings are always relatively quiet, but by the end of week one it was clear that there was a discernible Olympics knock-on effect – with people obviously choosing to stay home to watch the sports on TV rather than come to the Burgh for a bit of art or live entertainment. Many venues, though, chose to have the Olympics screened in the bar, so you could get the best of both worlds – see a show and catch up on the medal count on your way in or out.

My first few days at the Fringe are always my favourite time – there’s an easy pace, and I spend my time picking and choosing from favourite companies or interesting looking shows. People often ask me how I pick and choose from so much on offer, and the answer is that initially I tend to go for shows presented in curated programmes within the Fringe: Escalator East to Edinburgh are an annual regular, joined this year by a North East producers’ venture called Northern Stage at St Stephen’s, housed in what will inevitably always be known as the former Aurora Nova venue. There was also the Polska Arts programme of top Polish companies, including neTTheatre, KTO, Song of the Goat, and Teatr Biuro Podróży who are presenting not one, not two but three outdoor theatre shows at the Old Quad for this year’s Fringe: old favourite Macbeth(previously shortlisted for a TT Award), outdoor theatre classic Carmen Funebre, for one night only as an Amnesty International benefit (and what with the Pussy Riot outrage and all that, Amnesty are big on this year’s Fringe), and an Edinburgh premiere for new show Planet Lem. I’ve seen the first two and look forward to the third…

I saw a fair few Escalator shows, and didn’t, to be honest, feel the programme was as strong as usual, based on the four or five things I saw – but did very much enjoy Pete Edwards’ FAT. You Obviously Know What I’m Talking Aboutalso gets brownie points for including a scene in which a man watches a kettle boil, in real time.

Over at St Stephen’s, this was rivalled by a woman watching tea brew in real time – Faye Draper in Tea is an Evening Meal, a cheery and intimate wee show that which I saw (and very much enjoyed) before seeing another show co-authored by Third Angel’s Alexander Kelly, What I Heard About the World, which has been shortlisted for a Total Theatre Awards (more on that later).

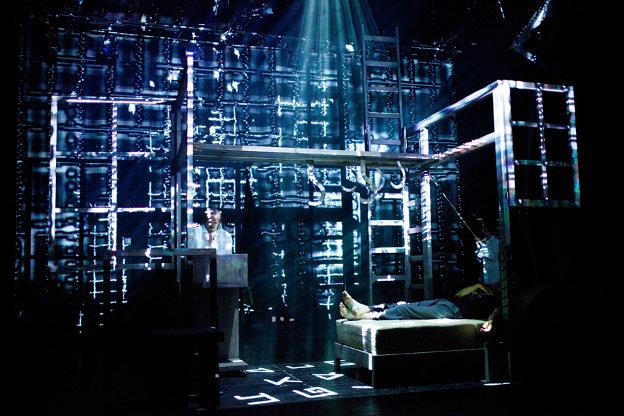

Over at the Assembly Roxy (what was the Zoo Roxy last year, and the Demarco Rocket before that, and the Roxy Arthouse before that – veterans of the Fringe will know of it as Richard Demarco’s gaff!) I saw some of the marvellous Russian programme curated by Anna Bogodist of Derevo, who was awarded a Herald Angel for her efforts. I didn’t make it to DO-Theatre’s Hangman, but that’s a show I’ve seen before and strongly recommend – what I did see and love was Derevo’s wonderful new show Mephisto Waltz and Akhe’s wonderful old show Mr Carmen.

A small tale of how the right sort of PR can work: ages ago I got a Facebook message from a friend now living in Australia inviting me to a show she had connections with, a piece called (remor) by Spanish dance/theatre/circus company Res de Res, an eleven-minute long show set in a prison cell – the audience join the two performers inside the ‘cell’. I thus saw the show on the first day, flagged it up to others on the Total Theatre Awards team, and I’m now delighted to see it on the Total Theatre Awards shortlist in the Physical and Visual Performance category (alongside Mr Carmen and Mephisto Waltz).

I also made sure that I spent some time at the Traverse, as that is always time well spent. As a venue dedicated to new writing, not all of the work programmed is of interest to TT reviewers and assessors – but lines between ‘new writing’ and ‘new work’ grow ever blurrier, with so much new writing for the stage now crafted by actor-creators (Tim Crouch being a good example), and so many writers also interested in creating a ‘total theatre’ on stage, using whatever ways and means they wish.

Traverse hits seen in the first week include Bullet Catch and All That is Wrong(the latter now closed). Both of these have made it onto the shortlist. Late opener Monkey Bars by the ever-resourceful and interesting Chris Goode is also strongly recommended (I write this having just left the auditorium – review will follow soon!), and I loved Daniel Kitson’s play on making a play (yeah I know: theatre referencing theatre, so last year – but I loved it!).

Another venue that I made a beeline to was Summerhall – only in its second year and already established as a place to find a really eclectic range of experimental theatres of all sorts. Favourites there have included the Italian production The Shit, Amusements (by Sleepwalk Collective) and How a Man Crumbled by Lecoq graduates Clout Theatre (and yes, you’ve guessed – those three are shortlisted, as are Song of the Goat’s Songs of Lear and Teatr Zar’sCaesarean Section: Essays on Suicide, neither of which I have yet seen but both of which come very hotly tipped). NeTTheatre’s new show Puppet. Book of Splendour (also Summerhall) was an epic, intense evening. I didn’t exactly enjoy it, but I admired it! It’s closed now, so you won’t be able to see for yourself if you haven’t already. I must also mention h2dance’s Say Something, a really interesting dance/choral voice crossover (declaration of vested interest: I’m in it!), which is also at Summerhall. This piece will be the subject of a Being There feature, which will be online soon. I also tried very hard to see Square Peg’s contemporary circus piece Rime, which is in the same space (the wonderfully named Dissection Room) at Summerhall as h2dance, so I’ve been staring at their set/rig a lot in recent days – but after three attempts foiled by cancellations (due to the company first ‘not being ready’ to open, then suffering injury) I eventually gave up, and have sadly now missed it as it closed a few days back. Well, that’s the Edinburgh Fringe for you – there are always some that get away…

Things I have seen and liked at other venues include Look Left Look Right’s verbatim piece NOLA at Underbelly. And I want to flag up shortlisted show Still Life by Sue MacLaine which I haven’t yet seen in Edinburgh, but enjoyed greatly at the Brighton Fringe last year (yep, another shortlisted one!).

What else? Well, despite picking carefully I sometimes find myself in the dark wishing I were elsewhere. If I feel the show has some merit – particularly if by an emerging company – I review the work and offer what I hope is constructive criticism. In some cases, I just feel I have nothing to say other than ‘do something other than make theatre’ and I am not really keen on the sarcastic and scathing reviewer mode, so I usually just don’t write the review in that case. It seems pointless just publishing vitriol!

So now, off I go on my quest to see all the shows on the shortlist I’ve not yet seen – every year to date I’ve managed to see the complete Total Theatre Awards shortlist, and this year I intend to do the same. Wish me luck as you wave me goodbye – I’m off now to see two on the Emerging Artists’ list –XXXO and Juana in a Million. I have high hopes…