Cirque Berserk is a tightly-packed sensory and sensual ride which is thrilling, charming, comic and nerve-shredding, often simultaneously.

The Timbuktu Tumblers open the show and set the tone for what is to follow. A troupe of highly skilled acrobats, diving through hoops and building human pyramids, the act becomes more and more energetic as it builds to its finale, combining finesse with an assured execution which still feels effortless and relaxed. These characteristics are demonstrated in other acts too, where great skill is accompanied with playfulness. For example, the pounding rhythms of the drumming in the bolas – weighted cords used as weapons for hunting in Argentina, but here to create thrilling drumming rhythms – act of Luciano Gabriel Carmona and Germaine Delbosq, slow down at one point as Luciano gently swishes his long hair with the bolas, nearly combing it, provoking laughter and a sense of relief from the audience, before building up the tension again with flaming bolas which engulf the duo in the whirling fire. By contrast, the Revolution Troupe from Cuba present a nail-biting springboard act, whose somersaults only just fit in the stage of the EICC. At the end of their acts the artistes pose and stare calmly out at the audience, with entirely justifiable pride. Other acts, such as the graceful aerial straps act by Jackie Louise, provide punctuation marks in the driving energy of the show.

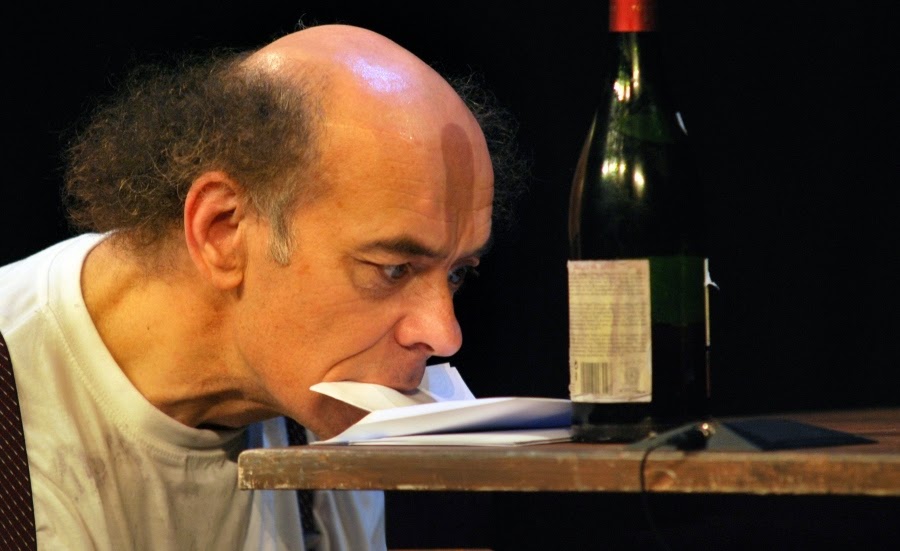

Many of the acts are self-contained – nevertheless, there is a strong theatrical frame to the show which meshes the acts together so that they criss-cross each other and intertwine. This is most evident in the storyline of Paulo Dos Santos, whose clowning in his repeated attempts and failure to plug in the cable to switch on the Circus sign hanging above the stage, is both comic and touching, as at the same time he tries to woo one of the dancers who intersperse the acts, repeatedly failing until he performs his own aerial straps act. In contrast the performance by wheelchair user Rafael Ferreira, who has no legs, and his acrobatic partner, Alan Pagnota, is a beautiful and delicate piece of circus theatre, in which they perform a faultless hand-to-hand balancing routine. This act is truly inspiring and moving.

Cirque Berserk creates a world in which much is literally and metaphorically upside down, particularly in the central set-piece in which many of the performers enter on a gypsy cart to create a continuous carnival of skill. Highlighted here are knife throwing from Toni and Nikol from the Czech Republic, foot juggling by Germaine Delbosq and Elberel Ebbe from Mongolia, who is brought onto the stage in a bottle from which she emerges to perform her contortion act and then, whilst in a handstand, threads a bow and arrow with her feet and fires the arrow at a target whilst upside down! Whilst the whole show is spectacular it culminates in the incredible motorbike finale, The Globe of Death, by The Lucius Team in which five bikers roar around inside a steel mesh globe, missing each other by a hair’s breadth, whilst raising the hairs on my head.

Framing this upside-down world into which the audience are transported are the eclectic music and sound, designed by Matthew Bugg, costumes by Dianne Kelly, the set designed by Sean Cavanagh, artistic direction by Julius Green and produced by Martin Burton. For me this show synthesises both traditional and contemporary circus to create an inclusive performance which cuts across boundaries. Judging by the large audience of all ages in the somewhat hangar-like space of the EICC, Cirque Berserk is truly popular in its appeal – and rightly so. As my nine-year-old companion said, ‘ Wow! Everyone should see this circus’.