It’s refreshing to see Shared Experience in the new Arcola building. It’s rough around the edges, has plywood flooring here and there and it feels like a space in which new and exciting performances will take place. Polly Teale and Nancy Meckler’s company were one of those who lost their Arts Council funding this year, perhaps because their work had become slightly predictable.

Refreshing indeed then, to see Teale’s direction of Speechless harking back to their glory days of The Mill on the Floss and After Mrs Rochester. Those productions had an urgency and power that leaped off the stage and grabbed an audience’s attention. Fusing an evocotive soundscape by Peter Salem with a minimal and rough design by Naomi Dawson, Teale presents us with a rich theatrical story of a pair of teenage twins who have stopped talking to everyone except each other.

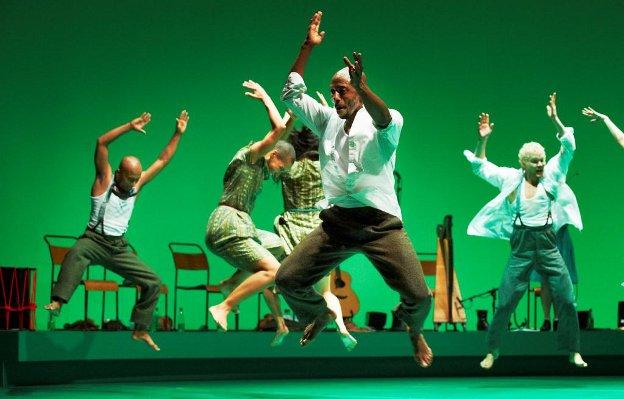

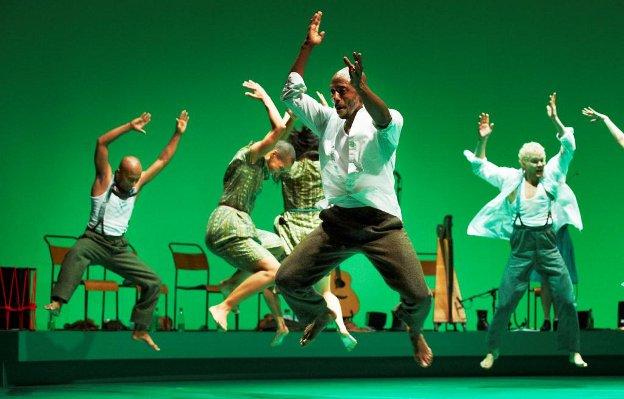

An adaptation of the Marjorie Wallace book The Silent Twins, the play allows us into the bedroom – the hidden world – of these twins who have ostracised themselves from society. They’ve been kicked out of school for violent outbursts and for their refusal to speak and engage with the teachers, fellow pupils and parents. Over 90 minutes, exceptional actresses Demi Oyediran and Natasha Gordon embody the twins with compelling energy. Their physical connection with each other is at the heart of the entire piece, and Gordon and Oyediran are incredibly in-sync with each other, whether it’s slowly dressing in detailed unison or the tiniest flicker of a look into each other’s eyes telling more than words ever could.

The power of physicality shines through Teale’s tense production, which spirals towards an inevitable tragedy. When the girls special needs teacher finally thinks she has cracked them the twins simply turn their backs to her again and again. It is infuriating, intriguing and heartbreaking to watch two young women manipulate each other, their lost mother and all around them through their silence. It left me looking forward to more gutsy and important work from Shared Experience.