The vast stage at Zoo Southside is covered by white silk, the outline of a lone body enveloped by it. Images of lapping water melt into the swathes of white. Is the body a corpse? Is it floating peacefully in the water? Coupled with the water’s sound and by delicate piano notes, it is mesmerising, lulling and haunting all at once. The body is that of Marc Brew, a dancer who woke up in a hospital bed paralysed following a car accident. The doctors told him he would never walk again. For Now, I am vividly depicts his story of rebuilding his body.

The vast stage at Zoo Southside is covered by white silk, the outline of a lone body enveloped by it. Images of lapping water melt into the swathes of white. Is the body a corpse? Is it floating peacefully in the water? Coupled with the water’s sound and by delicate piano notes, it is mesmerising, lulling and haunting all at once. The body is that of Marc Brew, a dancer who woke up in a hospital bed paralysed following a car accident. The doctors told him he would never walk again. For Now, I am vividly depicts his story of rebuilding his body.

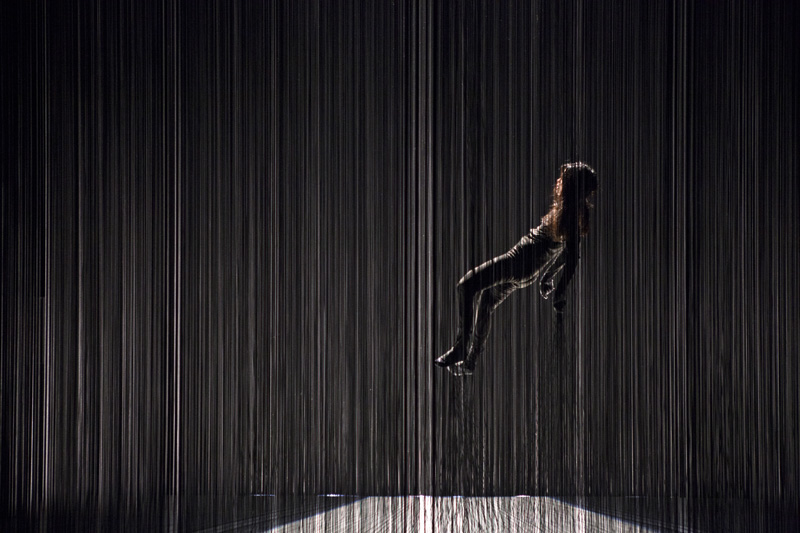

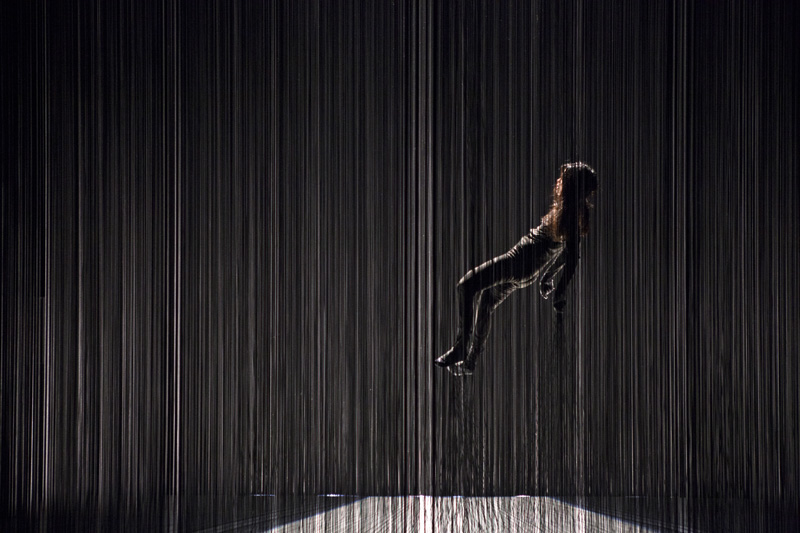

It is a painfully beautiful performance. The silk sheet is pulled to reveal Brew’s upper body fighting to move, valiantly driving forward. Andy Hammer’s lighting picks out the tiniest details within the vast setting – a finger twitching, darting eyes, the panicked breath of the man’s bare chest rising and falling. Brew’s detailed and subtle choreography draws us into his psyche. His muscles ripple as he pushes himself up and I find myself urging him on. Jamie Wardrop’s visuals of water and circular patterns gently echo the sinews of Brew’s body as he slides his body across the stage, wrapping himself in the swathes of silk and pushes himself onwards.

It’s a quietly grueling performance that never wallows in self-pity. Instead it is a passionately expressive experience that powerfully portrays the loneliness, struggles, and beauty of recovery and rediscovery.