If science and philosophy did not sit comfortably within theatre then last year would not have seen the frustratingly engaging Schrödinger from Reckless Sleepers or the beautifully desperate The Writer from Ulrike Quade. Yet somehow Curious Directive, who set out in their manifesto to ‘interrogate the simple role which science plays in everyday life’, have produced a work that is emotionally sterile.

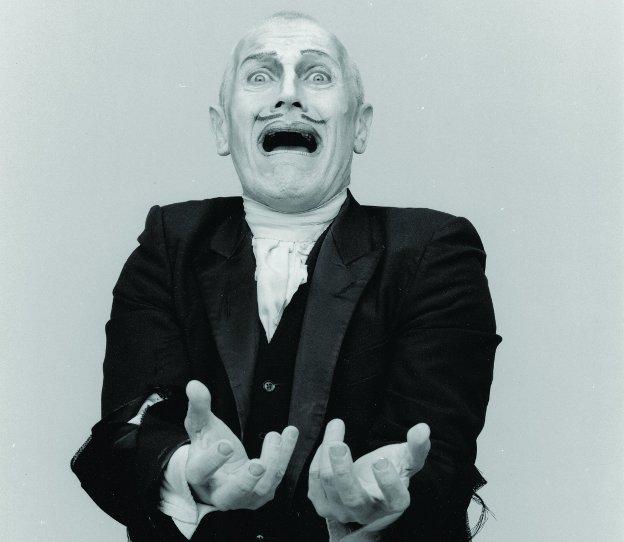

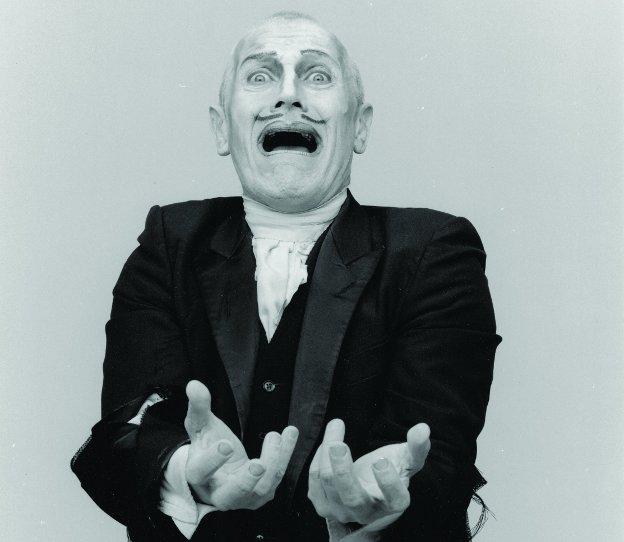

Your Last Breath interweaves four stories, setting different time periods and generations in parallel through a montage of scenes that allows the audience to gain insight into the potentially unseen connections and shared histories of the narratives. In 2011, the present day, Freija travels to Norway to scatter the ashes of her father. Her story, played by Karina Sugden, is compelling and the heart of the narrative. In scenes with her guide (portrayed by Gareth Taylor) we find glimpses of depth and despair as their relationship blossoms and her personal connection to home is tested in the journey they take together. Yet this is hidden for the most part as we continually cross-cut between other moments in time.

The connected themes of mapping a personal archive, self-discovery and life are overworked and painfully obvious as we jump to a British cartographer in 1876 mapping the same region of Norway, guided by an elder relative of Freija’s present day guide. Meanwhile a curious forward flash is made to 2034 as a corporate salesman pitches a medical breakthrough in cryogenics, inspired by the forth story from 1999 in which a skiing accident marks a catalytic changing point in the way doctors perceived the frozen human body. Further family links are established and implied through the course of the action but none really connect or excite in the moment of their unveiling. Ironically the audience is left cold.

Sugden and Taylor aside, the acting fails to engage and what, in places, could be moments of intense despair or poignancy fall flat, becoming rather awkward. In a production of technical excess, where video projection is used to the point of distraction on both the stage floor and rear set, and an incessant piano score dominates rather than compliments, the direction feels rushed; actors physically spin in and out of scenes, mimed actions sit awkwardly alongside the physically present, while the application of simplistic physical theatre and Release seems slapdash.

I applaud the sentiment that the company seeks to find ‘responses rather than answers’ in their work, and under the weight of their response presented inYour Last Breath there is a heart. No matter what you are exploring, connection to your audience is key and sadly the show fails on this front. But that there is a heart at all means there is hope for it to be rescued, and perhaps a strict dramaturgical editorial process may help to rediscover it anew.