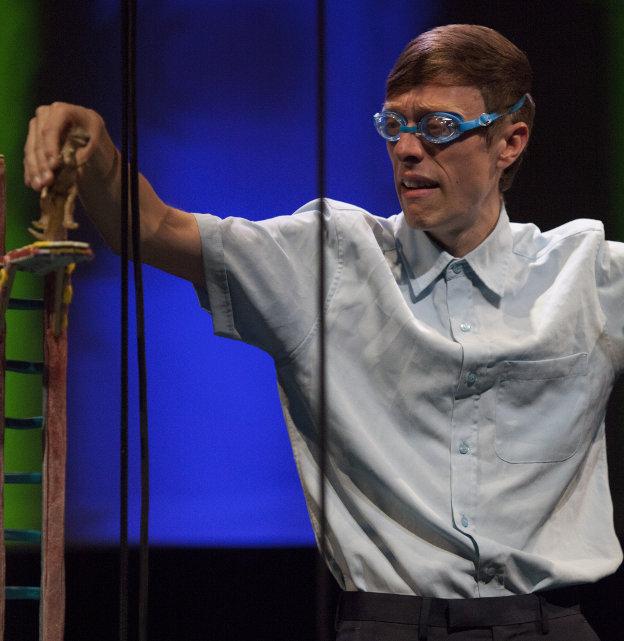

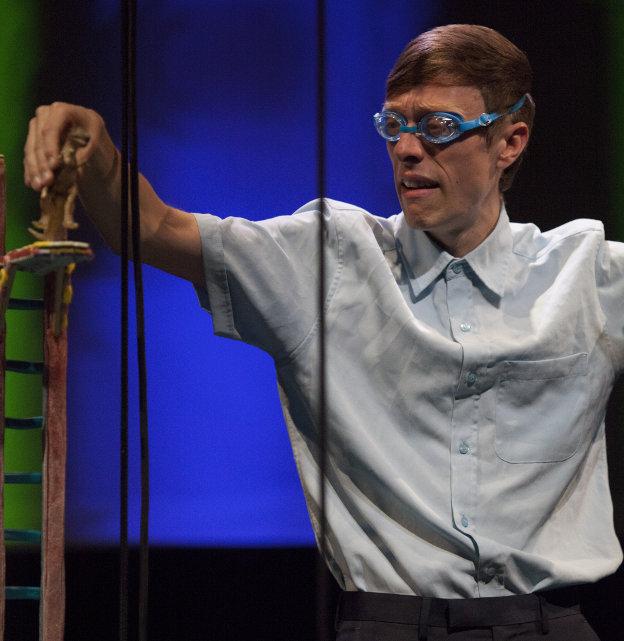

I Could’ve Been Better takes us into the world of the wonderfully unique James, a thirty-something social oddity. Gangly in limb, adorned with a nondescript blue shirt tucked deep into pleated plain trousers that hover at his ankles above verruca socks, he stands with his back toward the incoming audience.

As we take out seats, rarely does he let his attention slip from the film of an out-of-focus figure projected upon a large screen at the rear of the space. Its footage constantly evolves and revolves around and through a dreamlike milieu of domestic chores as we glimpse a figure in iconic yellow marigolds who at times appears to incongruously shadow-box as much as wash dishes. This presence is James’ centre, it is the Sun in his universe and his reason to be. Surrounding it, as part of Chris Gylee’s set design, are the objet d’art more befitting a child than a grown man: toys, a wooden railway, a swimming pool made of sweets, and a cardboard cut-out of Duncan Goodhew to name just a few. Each holds an invaluable worth and is deftly brought to life by James as he welcomes us into the cut and thrust of his life as a Railway Station Announcer in a sleepy English hamlet.

Jimmy Whiteaker’s performance as James deftly mixes comical physicality with a sense of the truth and realism at the heart of this character’s mixed up world in a way that is disarming and extremely powerful. The performance begins with the words, ‘Nothing is Happening’, and in a similar way this false start somehow unsuspectingly draws us into a tale which on the surface is very funny, yet is also deeply poignant. For here is a world of failure; of could-have-beens and almost-hads. It is at heart a classic comical tragedy, with our protagonist the victim of circumstance and his own inability to succeed.

With the spoken narrative told in the present tense, Whiteaker vibrantly lives moments both past and present before us in a desperate struggle through which failure is ultimately celebrated rather than cursed. From the nervous heights of a diving board, to the boredom of waiting for the delayed 4:14 from Biggleswade, we are taken on a unique journey. Acknowledged through spontaneous improvisation, we are witnesses to his attempts to succeed, but this breaking of the fourth wall never truly detracts from the world – by being involved and connected with James we love the obscure fool all the more. Indeed James doesn’t think in a linear way, and so for the man ‘who has never been on a train’ it seems appropriate that moments of spontaneous distraction should be encompassed by the performance as he recollects how at 30 he entered an over 10s swimming competition to attempt to defeat his 12 year-old nemesis, Veronica ‘ShitFace’ Barr.

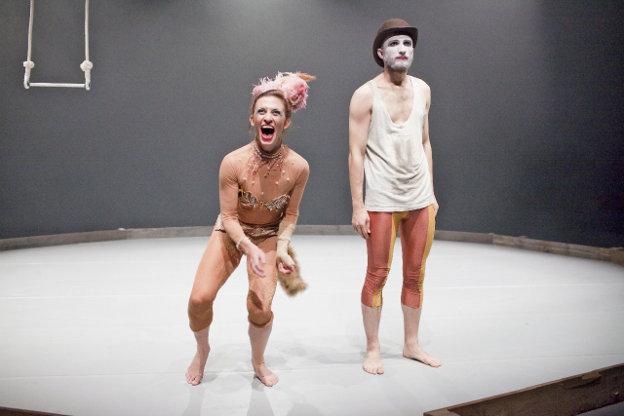

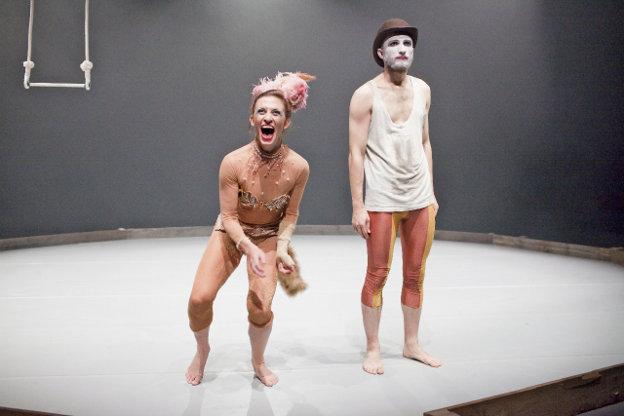

It is ultimately the strength of this wondrous company that, as with their previous production You’re not doing it right, they effortlessly strip back external perception to reveal the heart of a character with simple key changes of dramatic tone. The life of this man is not simplistic. He is beautifully complicated and the song ‘My Funny Valentine’ has never felt so appropriately applied than here within the world of our station announcer’s life.

Anna Harpin’s direction of the tragic lives of misfits continues to be intelligent and real. Ending with points failure and delays at the station the denouement of I Could’ve Been Better is beautifully heartbreaking, and Idiot Child is becoming a company not to be missed.