From Radical Self Love to Intersectionality via the Wheel of Consent – artist Rowan Prescott Hedley shows us their path to a theatre that is beyond binaries

I’m sat on a slightly-too-upright stacking hotel chair, a bit too warm and in a stuffy room that’s not quite large enough for the number of people in it. I’m at the Edinburgh Fringe watching a show from page one-hundred-and-something of the programme and despite the rising sensory overload, I am perhaps the most comfortable I have ever been.

In retrospect, this was a pivotal moment for me. At the time I was so unaware of the significance that I discarded all evidence of the performance or the performer. An aggressive reminder of the transience of theatre.

What I do remember is that the show was described as ‘Gender Fuck’ and in 2016 this was new language to me. Having been told to expect ‘gender performance or expression which mixes traditionally feminine and masculine elements in a way which subverts norms or roles including those of the LGBT+ community’, I was expecting another eccentric drag act, talking about how gender is a construct and we’re all actors, or it is real but it’s fluid, or… or… What I got was an experience that transcended all binaries.

The performance spoke to my working class roots and middle class education. My woman-ness as a child socially conditioned into the neurology of a woman and someone who’s not a woman at all. My ability and disability, somehow without using the context of ‘disability’ at all. It spoke of age but neither young or old, nor both, nor in-between. This experience started me on a journey to identify emerging theatre transcending social binaries, to question why this is important, and to propose a name for the approach producing such theatre outside binaries – Radical Self. I will share this journey with you.

It is important to note that I am white, with a mono-ethnic upbringing. At the time I saw this show I was only beginning to learn what I didn’t know regarding racism, so the performance could well have centred a white experience and I wouldn’t have noticed. Since then I have been deconstructing my internalised white supremacy and bias but will not have removed it from my analysis entirely.

The show was a one-hander, prop heavy and tech light. Anecdotes, examples, and experiments all delivered searingly vividly, in a space of about 30-feet square, told the story of the performer’s journey to uncover their own complex identity and deconstructed wider societal norms in the process. The performer was white, in their 30s-ish, non-binary or genderqueer or maybe both, used ‘they’ pronouns (at least in this context), slim-ish, short hair, and had an air of experience and compassion but not one to suffer fools.

It’s about thirty minutes into the fifty-minute show and I’m stood on the stage, by which I mean three feet in front of my chair, with three other audience members. We are all wearing a larger-than-life-size cardboard mask of the performer’s face, who is using us to illustrate the breadth and connectedness of reality – in this moment we five are all the same person, Polly, encompassing all the differences and contradictions spanning each separate life into one presence. The performer is explaining how ‘Sliding Doors’ and parallel universes exist within everyone of us and how in that way we are all the same, we are all everything and nothing –Schrödinger’s humans.

The rest of the audience audibly grasp the point and the performer sighs with pride, as the four of us return to our seats, without our Polly masks.

In the following ten or so minutes, the performer takes questions, responding from different identities by changing a piece of costume, their voice, or their physicality. Sometimes, they don’t actually answer the question but instead ask another or state something seemingly unconnected, though relevant, to whichever identity they were in, prompting other audience members to propose their own answers. Inside this dance of ideas and interaction it felt like the theatrical norms of performer and audience melted away. We merged together as a room full of humanity, sharing experience in different but intricately overlapping ways. There was no either, both, or in-between, we collectively and profoundly transcended social binaries.

Editor’s note: All attempts to find out who this Edinburgh Fringe 2016 performer might be have failed! If anybody reading this does know their name, please enlighten us!

I have struggled to find a word or phrase which embodies the scale of this experience. It’s possible this is a challenge not with language but with meaning. In a society immersed in binary categorisations of everything, how can we expect our current language to reflect anything else? I propose the term ‘Radical Self’, which connects three relevant concepts: Radical Self Love, particularly as formulated by Sonya Renee Taylor in The Body is Not an Apology; The Wheel of Consent modelled by Betty Martin, and Intersectionality coined in the 1980s by Kimberlé Crenshaw.

I surmise that creative practitioners use a Radical Self approach to interweave these three frameworks and create theatre outside binaries – performances which invite individuals to come together and experience, collectively. These events would be underpinned by accessibility strategies founded in dignity and radical consent: audience and performers could blur together as the process of giving and receiving information and emotion is shared throughout the space, and nothing would be categorised – each person would relate to what they could and learn from what they couldn’t. Ideally, this would create a theatre experience which is radically transcendental and, hopefully, decolonised.

This idea of theatre outside binaries as a product of Radical Self approach, was cemented for me with Zoe Coombs Marr’s Trigger Warning (Edinburgh Fringe, 2016) which was the sequel to Dave (Edinburgh Fringe, 2015). Coombs Marr delivered her classic toxic-male-standup clown as he tried to evolve following damning critique of his stand-up show (the stand-up and implied critique was the content of Dave).

Dave signs up for Gaulier clown classes and discovers his inner clown is Zoe, who is the polar opposite to Dave in attitude and physicality. Zoe the clown apologises for Dave’s behaviour, despite also being the writer and performer, Zoe, in a cycling question of ‘Who is whose clown?’.

At halfway through I thought the piece was depicting a clown discovering his own trans-ness. By the end I was clear that the performer and her clown and his clown were all one and the same. This didn’t mean that the performer was gender fluid or trans necessarily, in fact she said as much at one point; it was outside the gender binary and even the cis/trans binary. It was neither either, nor both, it was all. I didn’t have the words for it then, now I call it Radical Self.

Identifying the specific elements of Radical Self followed organically from a combination of learning about society and communication outside theatre, and other performances I saw.

The first element of Radical Self is Radical Self Love. This is in part the practice of identifying which oppressive structure has built the particular negative voice in your head about yourself or anyone else at any given time. This voice is often the expression of ageism, ableism, sexism, racism, queerphobia, and others. This practice contributes to a collective move away from prescriptive categorisation by refusing to engage with it regarding ourselves and others.

Many contemporary writers and performers utilise elements of Radical Self Love to name and deconstruct systems of oppression. Perhaps the most impactful recent illustration of this is Hannah Gadsby’s Nanette (Melbourne International Comedy Festival, 2017)which, amongst other analysis, named and challenged Hannah’s experience of, and internalised, sexism and homophobia.

The second element is the Wheel of Consent; a radical approach to understanding and enacting consent practices towards other people by yourself, towards yourself by other people, and towards yourself by yourself. It seems to me to be a way of healing colonised conditioning and epigenetics resulting in not listening to our bodies, denying other peoples’ experience, and multi-billion dollar industries propped up by crushing advertising.

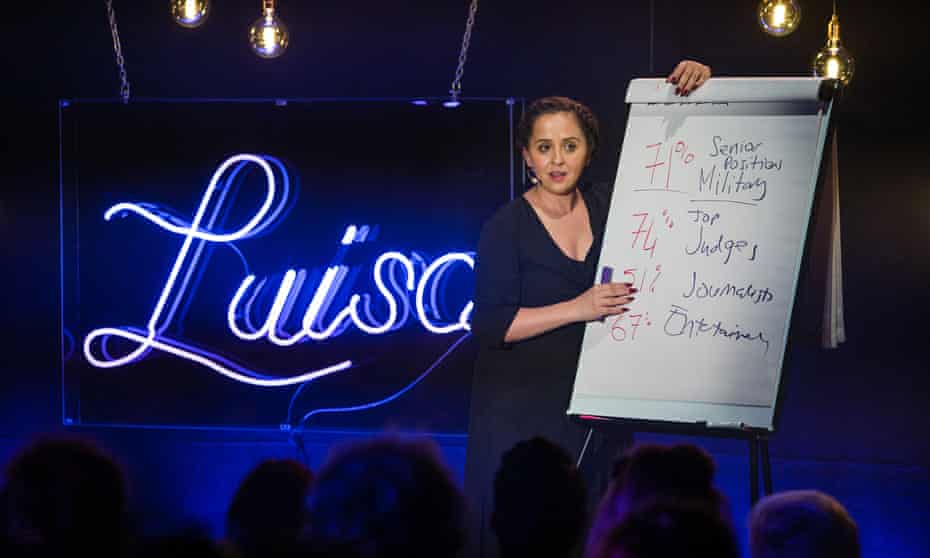

An example of this is Luisa Omielan’s Politics for Bitches (Edinburgh Fringe, 2018) which discretely introduces political frameworks touted as ‘too complex for people outside accepted company’ – in this context, women – in a way which highlights how simple these frameworks actually are. In doing this, Luisa Omielan liberates the audience to form their own informed consent about matters which directly affect them but where their autonomy has been historically removed, such as around financial decisions and investing.

A personal favourite and honourable mention is Hannah Gadsby’s Douglas (Arts Centre Melbourne, 2019) which is the best example of a show structure which supports neurodivergent consent that I have ever seen. Hannah discusses her own autism in this show and lays out the contents of the next hour right at the beginning. This opening has comedic value later on but also allows neurodivergent people to be prepared for the journey of the performance which is so rare and makes for a much deeper experience.

Finally, the third element of Radical Self, Intersectionality, is a framework to understand how people are affected by multiple discriminations and disadvantages which intersect to create overlapping and interdependent systems different from the sum of their parts. If we are not intersectional, we leave people behind. Originally specifically about black women, this term has expanded to become increasingly common in contemporary writing and performance.

One show which centres this framework is Inua Ellams’ Barber Shop Chronicles (Dorfman Theatre, National Theatre, 2017) which weaves culture, age, and black masculinity into a ‘tapestry of unfiltered stories’, as described by Brooklyn Academy of Music at their website on the New York premiere in 2019

Having identified these elements I came to the question of public reception of Radical Self and perception of theatre outside binaries. Without opening up reception theory analysis, it became apparent that individuals steeped in a colonial culture of binary categorisation will likely struggle to experience theatre outside binaries in a way in which un- or de-colonised cultures won’t.

I saw Vacuum by Cie Philippe Saire at the Best of BE Festival, Circomedia, in 2016. Two bodies moved in and out of light from two horizontal blue strip lights, whilst all else was in darkness. I was fascinated by the shapes of the body parts, the highlights and shadows, and had never visually seen bodies in this way, so removed from all context. It felt very freeing. This seemed a potentially transcendental piece but was easily categorised through a gender binary lens on BE Festival’s own description of the piece on their website which specified ‘two male forms’.

On the same bill there was a piece called Situation With Outstretched Arm by Oliver Zahn. One person stood holding a full right-arm salute in positions around the stage as a semi-academic presentation played behind them documenting the origins of the pose before it was co-opted by the Nazis. I was similarly captivated by the person’s body as they held the pose for minutes on minutes, only dropping the arm to move to their next position, shake it out, and carry on. By the end their entire body was shaking with the strain. Again, a piece which to me seemed potentially perfectly placed to embody Radical Self was easily categorised into the gender binary, not least by Rina Vergano reviewing on Bristol 24/7 who effortlessly gendered the performer ‘she’.

In clear contrast, The Angel Rose Artist Collective demonstrates how collective action and communication from a place outside of colonisation and closer to indigenous practices, effortlessly transcends these binaries as they are not entrenched in a way in which needs transcending.

The Collective describe themselves on their website as ‘A multilingual Two-Spirit (Native American Transgender, Intersex, Asexual, Queer+) led collective of artists, healers, educators, and advocates, uplifting Two-Spirit Nation and BIPOC Communities through art and land justice’. When Two-Spirit is ‘translated’ into western colonised understandings of queerness it tends to refer to ‘a person who has female-ness and male-ness’ but it is my understanding that this does not do the term justice. In our culture so readily and violently divided we cannot conceive outside of the prescribed categories – female or male or both or between –illustrating how entrenched these binaries are.

The Collective demonstrate this further in their own website description of the ‘one-persxn play Siwayul (Heart of a Womxn)’ in which ‘A Native American Trans Womxn seeks her place in the world. Guided by the Ancestors, she finds herself within her heart of a Womxn… and [empowers] the Ancestral Goddess within’ The play ‘ [Reclaims] Two-Spirit identity through Indigenous Salvadoran culture and diaspora’. A clumsily equivalent performance through a colonised British cultural lens would not be guided by ancestors in the same way if at all, compared to the much more harmonious and holistic Indigenous Salvadoran cultural context in which there is already some inherent Radical Self.

In this way ‘Radical Self’ could simply be synonymous for ‘humanity’, when humanity is in the process of being liberated out of categorising binaries and into complex and nuanced authentic human experience.

I want to note here that most of the examples in this feature relate to bodies, sexuality and gender, mainly as there is already discourse around the gender label non-binary and fluidity around sexuality. However, returning to the first example of that Edinburgh Fringe show by the unknown performer, Radical Self is theatre outside binaries which performs and discusses any and all facets of life, experience, and identity without contextualising through any binary categorising lens – be that gender, race, class etc.

I also want to acknowledge that there are reasons to specifically and emphatically depict navigating a world which disables you, growing old, or any other binary or between binary experience. Most significantly, telling these stories educates, liberates, and brings change. People in similar positions are validated and collective action is possible. One recent example, though admittedly from the screen, is the cultural impact of I, Daniel Blake by depicting the experience of living in Tory austerity Britain whilst receiving benefits, having a very low income, and being disabled. It is vital that we continue to tell stories which change outlooks or raise profiles in pursuit of a fairer world.

I pose that in tandem to this, there is a growing genre of theatre which purposefully transcends these binaries across depictions and discussion of any and all aspects of society in a practice of ‘being the change we want to see’ – this is why Radical Self is important. If telling real life stories of oppression is a vehicle for positive change, Radical Self is the destination. Using the framework of Radical Self to make theatre outside binaries brings together individuals who are conditioned see and treat anyone slightly different to them as ‘other’ into shared experience, humanity, and tangible compassion, one stuffy Edinburgh Fringe room at a time.

Rowan Prescott Hedley is a poet, playwright, songwriter, and performer based in Dorset. They use mixed discipline performance with improvisation and audience participation to engage traditional audiences in non-traditional theatre and question their assumptions, biases, and perspectives. They feature queer, neurodivergent, and intersectional themes in their work.

Rowan Prescott Hedley took part in the Total Theatre Artists as Writers programme 2021-2022.