One of the most anticipated events of this year’s Manchester International Festival, this collaboration between Adam Curtis and Massive Attack brings together the renowned documentary maker with some of the most innovative musicians of the last twenty years.

As is the case with all his films, the research Curtis and his team have undertaken is impressive. In the grandiose industrial space of the Mayfield Depot, eleven massive screens, surrounding the audience on three sides, show two hours of meticulously extracted archive footage. At times, the screens are lit to reveal Massive Attack playing behind the images, shifting the balance of attention between music and video, and generally this works well. As a whole, the night felt like an Adam Curtis film with a Massive Attack soundtrack, which, to be fair, was how it was presented. Nirvana’s ‘Where did you sleep last night?’ played when the narrative turned to Kurt Cobain’s self-annihilation through heroin, and the Archie’s ‘Sugar Sugar’ when the idealism of early 20th century utopias was presented on screen.

The film’s narrative begins in the mid 70s, and through a number of parallel threads explores a shift in the ideology of power that took place on both sides of the iron curtain after the utopian dreams of the early 20th century had dissolved. As Curtis presents it, this shift was towards a belief that the world shouldn’t be changed (since such interference is too dangerous), but instead should be managed through extensive data collection. This data could then be used to predict the future from the activity of the past.

In the light of the Edward Snowden affair, this emphasis on data collection should have felt particularly pertinent, though the relative lack of unfamiliar perspectives in the film – something I have always valued in Curtis’ other work – left me feeling like I was witnessing an argument already heard elsewhere.

Curtis’ storytelling was also perhaps less tight than in some of his other work: the links and parallels between the different threads of the story were either too convoluted to weave into a coherent whole, or perhaps were simply too weak to present a really gripping narrative.

On a more aesthetic level, the editing was, at points, very powerful. An extended montage of people dancing in different eras created a wonderful extra-temporal disco, and the titles that commented on how video brings the dead back to life, singing and dancing for us, were particularly poignant when overlaid on images of the long deceased.

Massive Attack’s soundtrack added a valuable additional layer, with reggae legend Horace Andy and Elizabeth Fraser of the Cocteau Twins both performing incredible guest vocals, but the preponderance of covers among the songs they played risked reducing the group to a covers band. Admittedly, a very good covers band, and a lot of thought had obviously gone into the selection of the songs so that they could best support the documentary, but with such top grade musicians on the bill the potential for something special to arise from within the collaboration felt somewhat missed.

On some level the night was incredible; the scale of the visuals and the archive footage surrounding the massive crowd, supported by these remarkable musicians as they built a soundscape around it was – at times – awe-inspiring, but looking back something felt lacking. At times the audience seemed confused about whether this was a concert or a film screening, and although small groups of people danced when the music allowed, the majority remained silently standing – hundreds of faces looking up at giant screens, absorbing the sensory support the music provided the video – and together created a visual image eerily reminiscent of the kind of footage I could imagine Curtis would track down.

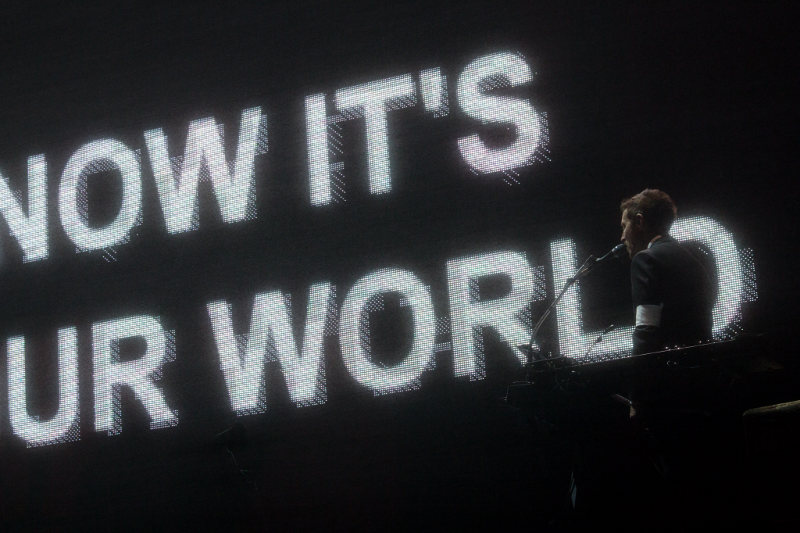

Going on the critique of television he presented, such passive engagement towards the screen is obviously something that matters to Curtis, and he moved towards negating such passivity with a call to arms in the encore. Whilst Elizabeth Fraser sang a beautiful version of Yanka Dyagileva’s ‘My Sorrow is Light’, text, six-foot-high on the screens around us, informed us that we can make anything happen, that we don’t need to remain passive, that the future is unknowable. Although sections of the crowd shrieked their approval, such calls to revolution felt incongruous. Having just spent two hours watching the masses be manipulated, and seeing how people like Jane Fonda and Donald Trump have imprinted their vision on the world, it was hard to feel inspired by such calls.

In some ways, such contradiction was emblematic of the whole night: did such an exciting collaboration meet its potential or, despite moments to the contrary, did it fall some way short of what was hoped for? I really didn’t want it to be, but sadly the latter feels a more apt description.

For more from Manchester International Festival see Total Theatre’s reviews of Inne Goris’ double-bill for children Once Upon a Story / Long Grass, Tino Sehgal’s installation work This Variation, and Maxine Peake / Sarah Frankcom’s Shelleyan poetry protest The Masque of Anarchy.