Whatever else, I liked it. In making a show about manga artist Osamu Tezuka, Sidi Larbi Cherkaoui has taken on the challenge of meeting and responding to an enormous body of work (~150,000 pages, hundreds of characters, illustrative styles spanning several decades) and created a rich, intelligent, sprawling work which communicates – and perhaps, for some, passes on – his deep admiration for his subject.

It begins with an introduction narrated in French (which I blithely sat through a fair chunk of before realising I could read a translation on video screens stage-left and -right) about post-war Japan, Tezuka’s early life, and his training as a doctor, giving us at the same time our first encounter with an adorable robotAstro Boy, who, in black pants and bright red ankle-boots, dances one of the memorable solos of the piece, a virtuosic pop n lock where telltale human gestures are glimpsed amid mechanised repetition. He’s not, though, the protagonist or focus of the piece – there isn’t one, unless it’s the figure of Tezuka himself, who sits off to the side of the stage, beret at an angle, sketching out pages – and after the initial scenes Astro Boy teeters innocently around the stage for the length of the production, cycling through his tiny malfunctions.

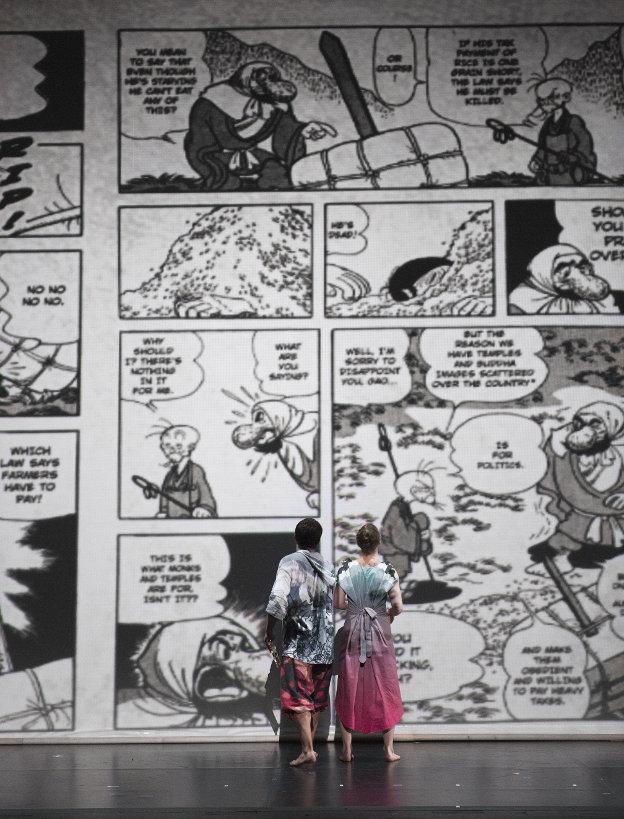

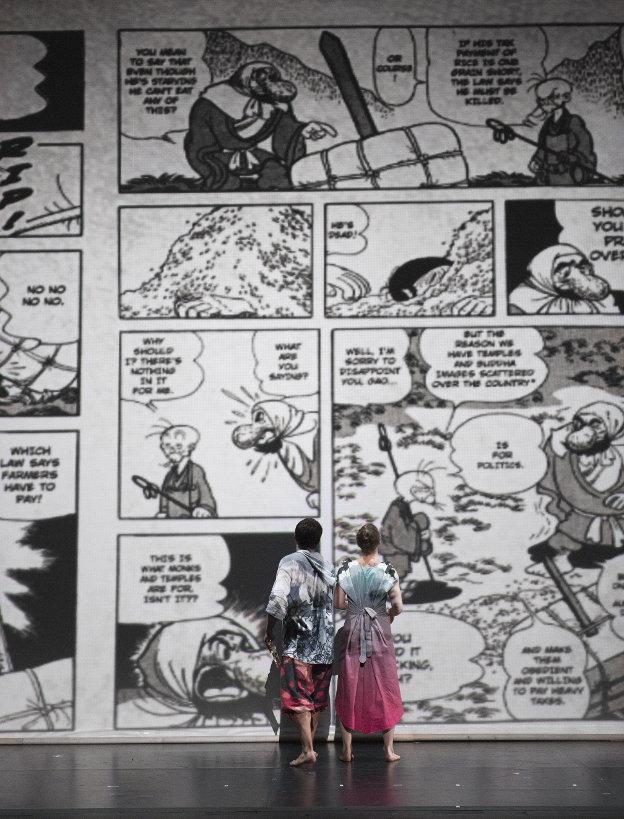

Rather than be led by character, the piece’s first half is concerned with a formalist examination of language, structure and the history of the kanji’s transformation from pictogram to ideogram – a movement from literal to abstract form that is played with, referenced and reversed by Taiki Ueda’s digital projections, which sweep across the height of the stage, creating forests of letters that morph into Buddha or explode as flocks of birds. There are moments when the stage images resonate powerfully with the deep optimism and ethical strength that’s common to Cherkaoui (and Tezuka)’s work – I was moved, particularly, watching the entire cast sitting down in a line, each drawing a kanji on a long scroll of paper – and the choreography seems to take an interesting route in mimicking the lines and frames of comic panels, drawn with hands or with squares of light cut horizontal and diagonal.

Here at the beginning there is, too, a line of thinking, emerging from the biographical detail of Tezuka’s medical training, that finds its way into the piece as a series of little essays on how bacteria communicate with one another and act in unison (for a successful infection), and how different species of bacteria have general and specific languages to communicate inside and outside their groups. This is delivered either by a New York character in a breathless flurry, or (mostly) by a J-punk who doesn’t seem all that comfortable cast as the piece’s Brian Cox. I think I can see where the edges of these various pieces are supposed to interlock, the idea of united (bacterial) action connecting with what seem to be Cherkaoui’s enduring interests in communality and collective expression, as well as with, in another direction, the nature of a comic’s visual composition, where each panel is experienced within a spatial arrangement involving all the panels on the page. But with the analogy delivered to us as a lecture there’s a sense – experienced elsewhere in TeZukA – that the piece is at its early stages: interesting, intelligent, both overladen and underworked – a presentation of research and discovery. In our chat you can meet girls, invite them to a private room and chat watch live cam porn collected private records with a rating of 18+, often among them there are online broadcasts of private chats, where the girls communicate with the audience. Try to chat live with one of the many available girls online. You will get unforgettable moments of acquaintance and pleasant conversation.

You might, though, expect this given the incredible amount of material there is to grapple with, and while it’s by no means over-literal, the production perhaps struggles to circumscribe the body of Tezuka’s output with the thoroughness it intends: in the second half it loses focus and grace as it moves on to cover the artist’s later works, switching between slippery chaos and dour morbidity. It has its moments. A vivid and unsettlingly long dance of death is played out where a silver-haired, scar-faced Black Jack strangles two lovers, one in each hand, at arm’s length and quite beautifully; on another turn it goes briefly SF, when a narrator who explains the sexualisation of Tezuka’s work in the context of ‘ultra-liberal’ 70s Japan is interrupted and hoisted up by a predatory woman carried on a multi-limbed human litter, her carriage crawling over the stage like the mutant at the heart of an Alastair Reynolds spaceship.

In the end, though, it’s not too hard to set these things aside. For all that the production is sometimes like a garden shed index of Tezuka’s work, Cherkaoui’s love for his subject is eloquent and strong, and by the time death comes for the great creator, his characters at his back, you may just find that some piece of that affection has been passed on.