Handspring Puppet Company are best known in the UK for their key contribution to the multi-award-winning NT production War Horse. Their earlier production Woyzeck on the Highveld – here restaged by director Luc de Wit, produced by a international conglomerate of festivals, and presented here under the auspices of UK Arts International, Puppet Centre Trust and Barbican’s BITE (amongst others) – is a very different kettle of fish…

Georg Büchner’s unfinished drama dealing with the dehumanising effects of medical science and the military on a young man’s life is, in Woyzeck on the Highveld, transposed to South Africa in the 1950s, and specifically to the exploited and depressed mining communities of Johannesburg. Where War Horse is a ‘suitable for all the family’ war drama, dealing with ‘difficult’ subject matter in a way that celebrates the human spirit, creating an emotional response in the audience without dragging them down into the depths of despair, Woyceck on the Highveld is definitely adult fare, pushing deeply into a depression that envelops all in its dark cloud; exploring the murky territories of mental illness, medical abuse, sexual jealousy, misogynist murder, and the terrible way that men are used as fodder (for armies, by doctors, down mines).

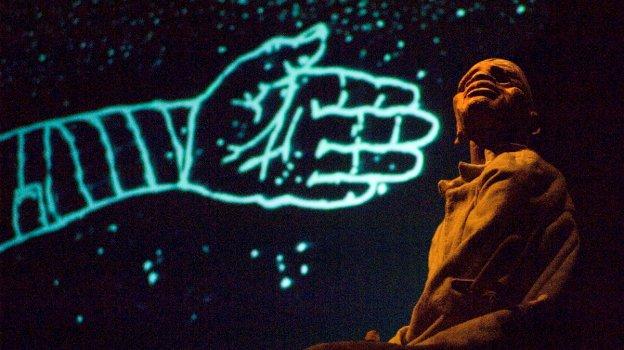

The mood of the piece is oppressive, the story played out under low ‘straw and steel’ lighting, to a backdrop of monochrome film of intensely, almost angrily scratched illustrations of bleak landscapes. It is not easy viewing, although the horror is alleviated a little by the introduction of the delightfully larger-than-life character The Barker (Mncedisi Shabangu) as a boisterous guide to the story who, megaphone in hand like a fairground caller, steps outside of the action to reflect rather gleefully on the terrible events unfolding, adding a welcome dose of Brechtian alienation. And, as always, having terrible deeds enacted by puppets does also lend a sense of distance.

William Kentridge, the director of the original 1992 production of Woyceck on the Highveld, and the creator of the beautiful black-and-white etching/animation work that is key to the piece, apparently was enamoured of his collaborator Handspring’s work from the very first, commenting that ‘each day of rehearsal has brought revelations of the things that puppets can do better than their living counterparts. Try training a rhinoceros to write or an infant to fly on cue.’

A rhinoceros – a very lovely raw wood construction – does indeed write, and an infant fly, in scenes in which the puppets, puppeteers, and onscreen action are in beautiful harmony; and it is these scenes that I enjoy the most. The doctor’s control of Woyzceck’s eating habits is a key chapter in the dark story (he is at one point ordered to eat nothing but peas), and there’s a very wonderful supper scene that mixes live action (puppets and visible puppeteers) and animation most beautifully, with the stark emptiness of the real table before us, laid with a white cloth, an empty glass moved round with a despairing lunacy by Woyzeck, whilst the chaos of a messy feast and spilled drinks erupts onscreen.

Other scenes played out between the puppets, on a raised platform upstage, in which the puppeteers are not visible, I enjoy less, and feel a little distanced from (literally and metaphorically), although I readily admire the enormous skill behind the work.

If there is a criticism it is that the story is often told in a kind of ‘shorthand’ that I think would be hard to follow for anyone unfamiliar with the original. Although it could perhaps be argued that Woyzeck is so beloved of contemporary theatre-makers that it might be hard to find an audience member who hadn’t encountered some version of the tale in recent years…

So yes, a good solid production, with outstanding animation work from Kentridge, excellent puppetry (of course!), and a marvellous performance from The Barker – but, for me, the piece as a whole is lacking the wonderful energy of War Horse, created with Tom Morris, and missing the gorgeous intimacy of Handspring’s most recent UK work, Or You Could Kiss Me, created in collaboration with Neil Bartlett. I’m becoming very aware that Handspring’s work is defined by who the company collaborates with. It is of course no bad thing for companies to revisit old work and remount productions, but personally I’m more interested in the future, and really looking forward to seeing where they turn next!