Theatre maker, performer, and clown Andrew Simpson reflects on The Party Shrimp And The People And Things That Taught Me To Do Theatre Good

Today

Most of the time when following a creative intuition, I have absolutely no idea what is going on, how to make sense of anything, and very little clue whether I am onto something genuinely interesting and worthwhile or just wasting my time. However, the process of making something, learning from it, and making again is cumulative. All the different experiences I have had whilst learning and my experience making theatre tells me it is all a hodge-podge approach of trying things out, seeing how they stick, and working from there. There is no definitive right way or school to follow, no Sensei with the ultimate truth of devising, and nobody really knows what they are doing.

My practice and my approach to making theatre comes out of many disparate influences and experiences. I try to embrace them all in a DIY approach and resist my natural inclination to set everything in very precise terms and adopt an all-or-nothing mindset. I like to be surprised and to surprise, to find counter-intuitive solutions, and to connect images and ideas that do not initially seem to be connected at all.

With that in mind I’m going to tell you about The Party Shrimp.

2021

‘This is pure The Thick of It,’ my brother half-moans at the TV as home secretary Priti Patel bungles laying a wreath at the Cenotaph on Remembrance Sunday.

We’re in Greenisland, Northern Ireland, visiting Nanny and it just so happens to be Remembrance Sunday and we just so happen to have BBC One on.

The whole thing is a total performance: the politicians wearing their best serious, sombre faces to show the voters just how good they are at governing. Everyone’s movements are carefully choreographed, clearly rehearsed, and meant to give off a certain meaning. This is how we remember: We stand quietly. We do as we’re told. We’re tense. We go along with the choreography. And we do what everyone else does.

Today

I first started working on a theatre piece back in 2016.

I read an article in the Guardian about Radovan Karadžić, the former president of Republika Srpska (a breakaway state within Bosnia) who, to escape prosecution by the International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia, disguised himself as a spiritual healer; changing his appearance, voice and occupation to live as a fugitive for years.

I was fascinated by this story and all of its strange details: two different lives within one body. Two roles that seem worlds apart, but in reality betray the same quest for power, ego and control. How could someone transform completely in order to stay the same? How could someone carefully choreograph and rehearse their life for pure self-preservation?

At around the same time I was becoming fascinated by Charles Freger’s photographs of costumed, masked folk traditions and costumes from across Europe in his book Wilder Mann: The Image of the Savage. What would an urban, modern, contemporary version of one of these creatures look like?

I had an intuition that these two ideas should come together into one but I didn’t know how.

2009-2013

In many ways university wasn’t a very good experience. Sometimes it could be a genuinely stimulating time but at others the whole thing seemed like a bureaucratic exercise in writing clever words in order to sound smart. However, John (Dean) and Bianca (Mastrominico), of Organic Theatre, seemed to come from a different world in which what they personally said and did mattered, even if it was only within a tiny circle. Their motivation was completely different from the institutional logic of the university. For them, and for us, the details matter. You may look a bit strange, everyone might not understand you, but if you had integrity and commitment and paid attention to the details – especially the details that ‘didn’t matter’ – then you could create something, something special.

The details matter.

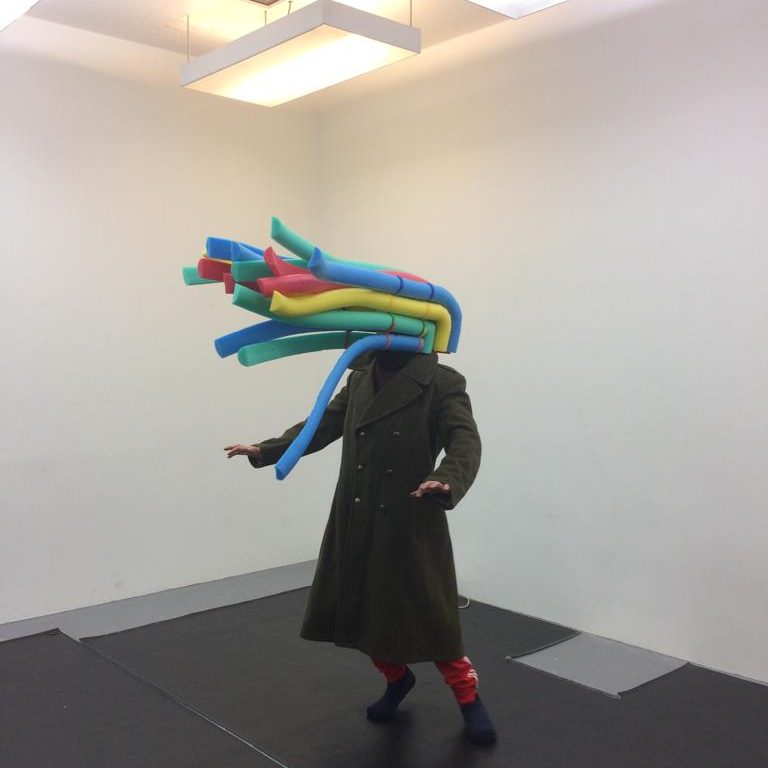

The Party Shrimp wears elegant, red winklepickers, thin yet smart crimson trousers, and a large blue military overcoat. Befitting their status as a general, adorning their coat are numerous beautiful medals, badges, and marks of pride and achievement. Upon close inspection these items reveal themselves to be made of seashells, fossilised starfish and other sea-themed items.

Under their coat is a hunchback, giving them an abnormal shape. And perhaps most strikingly, instead of a head they have a huge seething mass of brightly coloured sort-of tentacles. They are pastel-y yellow, green, red and burst out the collar forwards. There is no human head or eyes to be seen. Soft, playful tentacles curl and snake through the air, as if an explosion of colourful paint has been suspended in the air.

Today

My intuition told me that there is something here and that these two images: the war criminal living as an anonymous spiritual healer and the colourful, masked other-wordly creature, have a unity. I could not articulate how or why or what the ‘Questions I Wanted To Answer’ or ‘Themes I Wished To Explore’ were but I knew something stuck. I like to be surprised and to surprise, to find counter-intuitive solutions and connect images and ideas that do not initially seem to be connected at all.

Since 2016 I have been lucky enough to get support from various people and organisations (Anatomy Arts and Puppet Animation Scotland, you are legends) to continue to work on this project, alongside other things – to experiment, show bits of work, learn and develop. It has been a slow process of working backwards from this initial intuition, combining these images and slowly but surely finding a character and a whole world.

Wroclaw, 2013

After university, my good friend Jenny Logan and I went to Poland to do a workshop at the Grotowski Institute. Workshop leaders Gennadi Bogdanov and Alexei Levinski couldn’t be more different, and despite neither speaking English I got the distinct impression they disliked each other. Probably because Gennadi could be a bit of an arse. Alexei on the other hand, despite being in his seventies, was as spry and mischievous as an acrobatic. We took part in a workshop in Meyerhold’s theatrical biomechanics. Vsevelod Meyerhold was an actor and theatre director in Russia/USSR in the 1910s to 1930s. He developed a way of training actors that started with the body, with movement and physicality, not psychology. Stanislavski considered him to be his true artistic heir.

Meyerhold’s work was undoubtedly a product of his time: heavily influenced by the industrial and artistic transformations happening in post-revolution Russia. For a time, he was artistically experimental, new, fresh and different. But as the 1920s turned into the 1930s and political and artistic repression increased in the Soviet Union he fell out of favour. He was denounced as a ‘formalist’ who created a load-of-old-rubbish that ‘The People’ didn’t want or need, according to the authorities at the time. He was tortured and executed on 2 February 1940.

Jenny and I had a very intense time, throwing and catching sticks, making shapes and waiting, mid-pose, through the different levels of translation (Russian to Polish, Polish to English) during an exercise. The learning was completely different from reading about Meyerhold. You learned by moving your body. For the image to be correct, your arm had to be here, not here and these little differences changed the image and meaning for an audience and also changed one’s experience from inside, as a performer.

If you want to say anything you have to know how to speak.

The Party Shrimp is simultaneously imposing and loveable; completely improbable yet humbly existing just in front of us; huge and unwieldy and yet surprisingly spry and nimble.

The Party Shrimp may visit you somewhere nearby. They will come to explore, discover, parade, and perform their obscure rituals and ceremonies. They might even have a red carpet with them, to roll up, walk around on and roll up again. The Party Shrimp carries themself with pomp, grandeur and status and yet they are really such an old fool.

The plan is a performance for children of all ages that happens outdoors, in parks, gardens, squares and anywhere else a military general from another world might find themself.

2021

I sip my cup of tea, listen to the chatter of my siblings and frown at the TV. Curiously, when the cameras switch to any actual former members of the armed services, they all seem to be in good humour – presumably the whole thing is a chance to see old friends, remember who is not here, and have a bit of a laugh. After all, those in professions dealing with death are known for a gallows sense of humour. (We have to find some way to get through the darkness, right?)

We switch off the TV before the hypocrisy gets the better of us. We go for a walk round Greenisland. There are geese on the grass, fewer murals than there used to be, and the kerb stones are no longer painted red, white and blue.

Today

Until writing this all down I hadn’t realised the connection between one of the initial stories that inspired The Party Shrimp (a bizarre, dreamlike story from the horrors of the Bosnian civil war in the 90s) and something connected to my own life (some of my family growing up in 1970s Belfast). Both places, to different extents, marked with political/ethnic/religious divisions and violence.

The Party Shrimp doesn’t have a face, can’t speak and maybe (just maybe) the horrors of war, political violence, repression, and pain are not the ideal basis for an outdoor piece of visual theatre for a young audience. Then again, maybe this is the world we live in. Maybe this is the world that a young audience lives in. Maybe these are exactly the issues that art can and should face.

After all, I like to be surprised and to surprise, to find counter-intuitive solutions and connect images and ideas that do not initially seem to be connected at all.

Featured image (top of page): Andrew Simpson: The Party Shrimp. Photo by Rich Dyson.

Andrew Simpson is a theatre maker, performer and clown based in Glasgow. He makes original performance work solo and in collaboration with other artists, working outdoors and indoors. His practice is influenced by a diverse range of artists including Odin Teatret, Jackie Chan and Limmy.

https://andrewsimpsonactor.weebly.com

Instagram: @adrenalismscot