If I say ‘music theatre’ what do you think of? Glossy West End musicals perhaps; well produced and entertaining, but candyfloss – a sweet treat with no real substance. Cringe-worthy stage-school revivals of Cabaret? Perhaps, if you think a little harder, you might concede that there is innovative work of quality in the genre, such as the Theatre Royal Stratford East production of The Harder They Come, a vibrant and feisty reworking of the Jimmy Cliff cult movie which was taken up by Barbican BITE and has subsequently toured extensively across the UK, garnering positive critical appraisal, and bringing in those much sought after ‘new’ and ‘culturally diverse’ audiences.

But there’s more, so much more! On the evidence of performance work seen in 2010, I’d argue that ‘music theatre’ is a much broader genre than is usually discussed; that this genre is thriving; and that it is, and always has been, an important strand of the ‘total theatre’ family of performance practice.

My quest started with the news that renowned experimental composer, musician and erstwhile pop star Brian Eno had been appointed guest artistic director of the Brighton Festival 2010. Festival-goers were treated to a programme of multi-discipline performance events that threw up interesting ideas on the potential for ‘music’ not only to work with theatre, but to be a form of theatre. For example, the PR blurb for This is Pure Scenius!, a nine-hour durational/improvisational music work in three acts, announced that ‘the theatre of the music-making process is as enthralling as the music itself ’, and that it was ‘like a laboratory conducting an unknown experiment’ – which indeed it was. The stage features a regular enough set-up for an art-rock gig (guitars, drum kit, amps, synths, laptops, big screens for projections), but there’s a sofa and a table with a kettle on it set up in front of the stage. The musicians, who include Eno himself, Underworld co-founder/singer Karl Hyde, and keyboard wiz Jon Hopkins, come and go as they wish, and their upfront tea breaks become as much a part of the performance as anything else happening. It’s a really beautiful piece, aurally and visually. As is 77 Million Paintings, sited in Fabrica, an art gallery in a church that retains its original features (font and all). A batch of red sofas are scattered through the space, on which to lounge for as long as you wish to watch the ever-morphing abstract painting in light that unfolds, listening to Eno’s ‘wallpaper’ music, the piece originally conceived, as Eno puts it, as ‘a the next evolutionary stage in the fascination with the aesthetic possibilities of generative software’. Another lovely piece of sound-and-vision ‘theatre’.

Interestingly enough, the least successful of the Eno works I saw at Brighton Festival was the one that was ostensibly the most ‘theatrical’. This Is Tales of the Afterlives was based on Sum, a lovely little book of short fiction by David Eagleman, which offers a series of fantastical musings on potential afterlives. The stories are read by ‘local people’ of various ages, some of whom would call themselves performers, some who wouldn’t, these readings accompanied by a live score by Eno and a video piece featuring a series of slow-dissolve close-ups of individual faces. But the deliveries vary wildly in quality, and the piece lacks direction.

Far more successful, and my favourite Eno piece in the festival, was a late addition to the programme. The Speaker Flower Sound Installation, created in collaboration with poet Rick Holland, was a beautiful response to an empty, slightly distressed, Regency building, Marlborough House – a truly site-responsive work, featuring Eno-designed ‘speaker flowers’, which ranged from things that were literally flower-like emitting barely-audible sighs and whispers, to an Astroturf sound-lounge, and wooden ‘logs’ set up to respond to movements in the room. There was an elemental theme, with some rooms ‘watery’, some ‘earthy’. Holland’s text was represented written on walls, or in some of the sound transmissions: ‘my god is in the breath of crows’ says one; ‘words in there and the fountain can flow,’ says another.

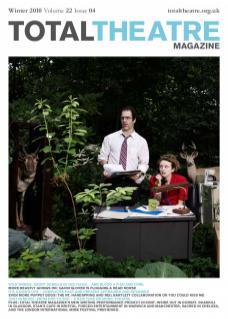

Other popular music megastars whose work edges into performance territory include the extraordinary Jónsi, lead singer with Sigur Rós. His solo show (also seen in Brighton, autumn 2010) merges music made with a gorgeous variety of instruments, – including a deconstructed drum kit, a glass Celeste, an ancient armonium and an over-sized metal xylophone which is bowed rather than struck – with beautiful animation, and a loose storyline of the encroaching of the wild on civilisation (there’s a lovely scene of ants carrying off a can of Coca Cola). This may sound like the Gorillaz’ Plastic Beach (which also blends music with animation; also reflects on environmental issues; also seen in 2010, at Glastonbury Festival), but the aesthetic is a million miles away: Jónsi’s is firmly rooted in the Icelandic world of the mystical imagery of fairytales, and legends of the Hidden People.

And if we are talking of people sitting on the fence between pop stardom and performance art, how could we not mention Laurie Anderson, who stepped out of the performance art ghetto to have a number one hit single with ‘Oh Superman’. It is telling that Laurie Anderson is regularly presented as part of the Barbican International Theatre Event (BITE) programme, rather than within that venue’s music programme, for it is indeed theatre – music theatre – of the highest calibre. Delusion, seen at the Barbican in April 2010, is one of her best shows for years; a gentle, dreamlike reflection on mortality, with the artist’s customary mix of treated violin (and other instruments); projection; light-and-shadow play; and poetic prose, spoken in a mix of voices, including that of her alter-ego Fenway Bergamot – who has a ‘treated’ voice, deep and moody, as he recites the story-song about the nature of time around which the piece revolves, ‘Another Day in America’. ‘Ah these days, all these days. What are days for? To put between the endless nights,’ he growls…

Other shows programmed for the BITE 2010 programme have demonstrated the Barbican’s continuing commitment to experimental music theatre, with a return to the venue of Heiner Goebbels with I Went To The House But Did Not Enter and a first time Barbican appearance for Catalyst Theatre with Nevermore, an exploration of the interplay between Edgar Allan Poe’s life and art. Catalyst’s unique form of highly visual and ultra-stylised music-theatre suits the subject matter perfectly. Nevermore could perhaps be described as a burlesque opera. The facts of Poe’s life are presented to us with an ultra-grotesque Gothic sensibility – terrible tales of tuberculosis, alcoholism, literary rejection, and romantic abandonment presented as larger-than-life cartoons. The show is a visual feast: the costumes a kind of carnivalesque re-interpretation of Victoriana; the set comprising a number of sliding screens, creating a (literally) multi-layered vision; the many marvellous props and artefacts including a pop-up book and a whole menagerie of ‘big head’ animal masks. Those who want to amuse themselves picking out the visual references to Poe’s stories might spot a grotesquely pounding Tell-Tale Heart; a Black Cat with Scissor-hand claws; and, across the back wall, alternating washes of colour that evoke the journey through the castle’s many-coloured rooms in ‘Masque of the Red Death’.

The ensemble of seven are superb performers: beautiful singers, and gifted physical actors. Nevermore was composed, written and directed by Catalyst Theatre’s artistic director, Jonathan Christenson, who has similarly created and/or performed in fifteen original productions for Catalyst over the years. His long-term collaborator is designer Bretta Gerecke, and together the pair have created a very special style all their own. Having followed the company from their first UK appearance with The House of Pootsie Plunkett, it was great to see them programmed at the Barbican. If I had to name one company that represented the best of contemporary music theatre, I’d pick Catalyst.

From gothic opera to opera ‘proper’. ENO have, in recent years, welcomed the physical/visual theatre community into their arms. Madama Butterfly, directed by the late great Anthony Minghella introduced contemporary puppetry to the mix in the form of Blind Summit. This collaboration paved the way for further unusual pairings with UK theatre-makers. Improbable designed and directed the Phillip Glass opera Satyagraha for ENO (and Improbable have a good track record for working with musicians, albeit of a very different sort – in works such as Shockheaded Peter, a collaboration with the Tiger Lillies). Blind Summit are currently (November-December 2010) working in collaboration with Simon McBurney of Complicite on another ENO production A Dog’s Heart, which also draws connecting threads back to that seminal Minghella production through designer Michael Levine, whose work for A Dog’s Heart is breathtaking (snow drifts, water floods, and blood flows across the stage; an every-which-way set that tilts and over-sized furniture that skews perspective; and the customary Complicite clever integration of moving image into the live action). The opera’s composer Alexander Raskatov worked closely with McBurney, breaking the rules with the inclusion of mediated voices (usually a no-no in opera, in my admittedly limited experience) through megaphone and ‘telephone’; the scuddering sounds of footsteps and the scuttling of the puppet dog across the stage; and interesting instrumentation that includes such things as vibes and a clanger-like swanee whistle. McBurney says that his work is always ‘intimately bound up with music’. Often in Complicite’s work music isn’t decorative or mood setting, it’s integral to the dramaturgy of the piece. As, for example in their production Shun Kin, a story of a master samisen player which features a real live master samisen player onstage!

There have been other extraordinary ‘cross-over’ opera productions this year. At Sadler’s Wells, Tanztheater Wuppertal brought an early Pina Bausch work to London – Iphigenie auf Tauris, her version of the Gluck opera. The orchestra is where you’d expect to find it (in the pit) but the singers (scores of them!) are placed in the boxes to both sides of the stage, so that their voices come to us from above and around like choirs of heavenly angels. Each main character has two people playing them: the offstage singer and the onstage dancer. The choreography has all the hallmarks of Bausch’s work – a mix of childish playfulness and intense adult sexuality. There’s the women’s characteristic tossing of long, loose hair; a boyishly sexy male duet in underpants; odd pairings of men in evening wear with women in loose silk nightgowns; a dance with a mirror; and a dance with chairs. All in the service of the tale of temple maiden Iphigenie’s disturbed relationship with her family: father Agamemnon tries to sacrifice her; she’s spirited away and years later dreams her mother has killed her father (true); then dreams she kills her beloved long-lost brother; inadvertently tortures and kills her beloved long-lost brother. In every scene – scenes which play with the notion of ‘dream logic’ to great effect – the music and the ever-more-beautiful visual pictures complement each other perfectly: you couldn’t describe one as illustrating the other; they feed off each other harmoniously, forming a whole experience of sight and sound.

Back at ENO, a major event for 2010 was their pairing with Punchdrunk for The Duchess of Malfi, a new opera (composed by Torsten Rasch with libretto by Ian Burton after John Webster), staged in a disused office block in East London. As is often the case with Punchdrunk’s large-scale productions, the narrative is deconstructed and rearranged into a series of looped performances set in a wonderful fantasy land of installations (which in this case include a forest of metal trees; secret fur-strewn dens in abandoned offices; and a cathedral replete with wooden pews and signs exhorting the value of purification). The audience, free to wander the building, encounter – in no particular order – scenes depicting or referencing Webster’s terrible tale of incestuous desire, insanity, torture, and child-murder. The story culminates in the execution of the eponymous Duchess. The audience are silently directed to all gather in one large space for the denouement: a familiar Punchdrunk tactic that in this case leads to a visually stunning, physically gruelling, and musically enchanting piece of ‘total theatre’ that is long enough and engaging enough to be classed as a show-within-the-show. Playing Count Ferdinand (one of the duchess’s terrible brothers) was counter-tenor Andrew Watts, who is currently performing in A Dog’s Heart.

‘Our previous productions have been operatic in intention, so we were crying out to do the real thing,’ says Punchdrunk director Felix Barrett (speaking on the More4 TV programme The Making of… The Duchess of Malfi). The challenges in Duchess of Malfi were obviously there in moving a whole orchestra (as opposed to a few nimble actor-dancers) around the space. Although it was a marvellous achievement, the production wasn’t perfect: the musicians sometimes struggled with the task of relocating discretely, and with staying in a neutral performance mode between set-pieces.

What you ‘do’ with the musicians is a challenge that many theatremakers face when creating music theatre. Of course traditionally they’d be in the pit, or to the side of the stage, but if you want a more integrated approach, there can (as demonstrated in the ENO/ Punchdrunk collaboration) be issues with keeping alive the world of the play if it is peopled by musicians who are not used to the notion of staying in character and maintaining a performance presence that is in tone with the aesthetic of the piece.

But if the theatre-makers are themselves musicians, then the odds on maintaining that onstage world successfully are increased. A theatre ensemble who have music at their heart is the ever-enterprising Little Bulb. All three of their productions to date (Crocosmia, Sporadical and Operation Greenfield) have circled around an interest in music. With Crocosmia, a trio of orphaned children remember their parents through their vinyl record collection. In Sporadical we get an abrupt switch in aesthetic for a cardboard-and-sea-shanty junk opera set at a family reunion. Operation Greenfield (presented at The Zoo Roxy for the Edinburgh Festival Fringe 2010) is another shift in tone, being the story of the emergence of a Christian rock band and their first gig at a local community centre. It works brilliantly because the actors playing the band are a band who can play; and because all the little details (learning to play bass by copying ‘Walk on the Wild Side’; niggling arguments between band members on whose songs get worked on; constant agonising on the band’s name) will feel absolutely right to anyone who has ever been in a band. The climax to the show, in which the band finally emerge in their angel-winged glam glory as ‘Operation Greenfield’, playing the most extraordinary prog rock number, is divine – and, you know, I have always had a soft spot for bands with girl drummers…

Also playing with the ‘let’s be a band’ idea, and also seen at Edinburgh, was Patchwork by The Honourable Society of Faster Craftswomen, in which Laura Eades weaves autobiographical stories of her relationship with female family members into the band-on-the-road motif (the band rather fetchingly dressed in odd-bod multicoloured knits). It’s an odd combo (in both senses of that word), but Laura’s onstage enthusiasm and energy as she half-sings half-recites her poetic text, and the accompaniment of some very lovely animated drawings, make it an interesting evening.

Another interesting onstage musical world can be seen in Dancing on Your Grave by The Cholmondeleys and Featherstonehaughs, choreographed by Lea Anderson and featuring the banjo-and-uke music of Nigel Burch (of Flea Pit Orchestra). The show, seen in the Brighton Fringe at Nightingale Theatre, is the story of a vaudeville troupe who are dead, but continue to tour regardless. Others breaching the gap between music and theatre in vaudevillian mode would include musical clowns and visual artists Foster & Gilvan, who under the banner Badstock Productions created Penny Arcade (a live interactive version of a Victorian penny arcade). Foster also appears with Unpacked Theatre in their version of the troop-of-vaudeville-musicians-on-the-road story, The Show Must Go On, which circles around the moving of an old piano, and the stories that piano has to tell.

Another Foster & Gilvan collaborator is Joe Bone (of Bane fame). These three are part of a loose collective of musician-performers working under various banners creating live scores for silent film (for example, a jazz-and-toy-instrument soundscape for The Patsy at BFI by Gwyneth Herbert); and bringing live musical performance into art galleries in response to pre-existing artworks (for example, in the Foolish Romantics show presented at the Quay Arts Centre, Isle of Wight, April 2010).

Someone who is an occasional member of this loose grouping, performing, for example, with Badstock at the Basement Bordello at Brighton’s Basement arts centre, is 1927’s Lillian Henley. 1927 have made a name for themselves with their groundbreaking mix of animated film, mime, storytelling, and live music, garnering numerous awards for Between the Devil and the Deep Blue Sea. Their new show The Animals and Children Took to the Streets is at BAC for the Christmas slot. ‘Lilly’s piano is at the heart of the work,’ said writer-performer Suzanne Andrade when interviewed on the making of the work. And rumour has it that 1927 will be tackling opera soon too... Lillian’s own solo work shows an ongoing interest in the integration of film, music and performance: earlier this year (April 2010), she was to be found hosting her own venture, The Palace of Varieties at Hoxton Hall, and playing her newly composed piano scores for Laurel & Hardy films.

And when Joe Bone isn’t being a Foolish Romantic and isn’t performing/creating Bane, Bane 2, or Bane 3 (which in itself is an interesting collaboration between a sole performer and a musician in the creation of ‘live film noir’), he’s a member of the Total Theatre Award winning company The River People, who this summer have been taking their particular blend of music and puppet theatre out of the theatres onto the streets (and into the woods) including at the Winchester Hat Fair in July, where they performed The Terrible Tales of the Midnight Chorus, a series of macabre Hoffman-esque vignettes, on a lovely wooden ‘gypsy wagon’.

Also on the streets of Britain in 2010 (and in the music venues and pubs too) has been Periplum Theatre’s 1000 revolutions per moment which is about pop, politics and posing; the search for the perfect gig; music and social change; remembering the soundtrack to growing up - and a whole lot more... It’s a genuinely site responsive piece, reworked for each town it visits – and music is not only an integral part of this show (with local musicians integrated into the fabric of the piece at each place), but is the very subject matter of the piece.

Other enterprising outdoor music theatre projects this year have included Kimmo’s collaboration with Paper Cinema, The Rock Charmer (see review in this issue of the magazine), brought to Inside Out festival in Dorset by producer Simon Chatterton, whose previous productions have included Siren, an indoor sound installation work featuring a score of whirring machines, and Power Plant, a multi-artist endeavour (collaborators including Jony Easterby and Anne Bean) which was an enormous success at the Edinburgh Fringe 2009 when it was sited at the Botanic Gardens, transforming the glasshouses and surrounding areas into a night-time magical kingdom populated by standard lamps, wind-up gramophones, flamelights, singing flowers, sculpted dresses, and mechanical insects.

The notion of ‘the theatre of sound’ came to the forefront in late 2010 with the announcement of the Turner Prize win for Susan Philipsz, who uses her own voice to create ‘uniquely evocative sound installations that play upon and extend the poetics of specific, often out-of-the-way spaces’. Her work Lowlands (presented at the Glasgow International Festival of Visual Art) features her melancholy voice recordings of a folk song sited under a lonely bridge under the River Clyde.

We are a long way from the West End musical here, but Philipsz’ Turner Prize win has come at an interesting time. There is currently an increased awareness of, and interest in, the theatre of sound: in sound art and sound installation; in performance work that uses sound and music in extraordinary ways; in collaborations between physical, visual and aural artforms and traditions of all sorts; in new operas and reinventions of the notion of ‘the musical’. Different artists will see themselves placed in different ways within all this, some defining themselves principally as musicians, some as performance artists, some as theatre makers, and some as fine artists – but ultimately it’s all about new sounds in new settings.

I’m all ears, and can’t what to hear what 2011 might offer up!

Music works, many and various, as referenced above seen at:

Brighton Festival: www.brightonfestival.org

Brighton Fringe: www.brightonfestivalfringe.org.uk

Edinburgh Festival Fringe: www.edfringe.com

Barbican BITE www.barbican.org.uk/theatre

Sadler’s Wells: www.sadlerswells.co.uk

ENO: www.eno.org

Hat Fair, Winchester: www.hatfair.co.uk

For more on the Turner Prize 2010 winner and nominees: www.tate.org.uk/britain/turnerprize

Unpacked Theatre continue to tour The Show Must Go On, and premiere new children’s show Robin & The Big Freeze December 2010: www.unpacked.org

Theatre Royal Stratford East production The Harder They Come was seen at Wimbledon Theatre, June 2010. www.stratfordeast.com

Periplum’s 1000 revolutions per moment was seen at Reveal festival. www.periplum.co.uk

Badstock Productions for Foster & Gilvan, Foolish Romantics, and Penny Arcade: http://badstockproductions.blogspot.com

Bane and other Joe Bone projects: www.whiteboneproductions.com

Complicite: www.complicite.org

Catalyst Theatre: www.catalysttheatre.ca

Punchdrunk: www.punchdrunk.co.uk

The Making Of…The Duchess of Malfi is screened 9pm on 4 December 2010 on More4. The Making of... is a series of three films on seminal recent productions co-produced with Arts Council England.

1927’s The Animals and Children Took to the Streets is at BAC main house, 8 December 2010-8 January 2011. www.19-27.co.uk | www.bac.org.uk