The links between puppetry and drama theatre go back a long way and they are perhaps bound together more inextricably than most people realise; like the strings on a marionette, once tangled they are difficult to separate again. The puppet, described by Edward Gordon Craig as the 'degenerate form of a god', has a history at least as old as the concept of theatre itself and shares similar origins. In literature as well as in drama, the puppet has excited the imagination of the artist – after all, Don Quixote 'tilted' at a band of marionette soldiers before he attacked a row of windmills! And, whilst not always 'centre-stage’ in the development of drama, the puppet was continually ready and waiting in the 'wings'.

However, the relationship between the puppet and the actor has long been an uneasy one and this may go some way towards explaining why the puppet has been absent from our dramatic stage for long periods. The emblematic nature of the puppet has often been at odds with the prevailing requirements of the drama theatre. Nevertheless, the unique possibilities offered by puppetry – the essential differences from, as well as the broad similarities to, the drama theatre – have continued to fascinate dramatists and theatre artists down the centuries.

Craig's dissatisfaction with the actor was, in large part, because of his perception that the actor could not make ‘a work of art' out of his body, but only ‘a series of accidental confessions'. To the artists who gave life to the modernist movement, the puppet offered the possibility of salvation for the theatre – a kind of redemption for theatre as an artform, that would save it from being simply the bourgeois diversion that they perceived it had become. In 1917 the Russian theatre critic Yuliya Slonimskaya wrote: 'The marionette does not imitate life. It creates its own fabled life, which bends creator and spectator alike to its own laws.’

Now, at the turn of the millennium, there is a palpable resurgence of interest in puppetry – among both theatre artists and audiences – as an expressive and creative performance medium. This renewed interest, this 'call’ of puppetry to the dramatic stage, clearly has strong parallels with that earlier time. Then, as now, theatre artists were looking to find new forms of theatrical expression; as an antidote to what they then regarded as the formal and moribund theatre of the day. Then, as now, the boundaries between performance disciplines became somewhat fluid as dramatists and theatre artists looked outward for inspiration. Then, as now, one of the ways in which a generation of theatre artists sought to stimulate and revivify drama was by opening it up to the world of the puppet. The rediscovery of puppetry (and just how many times does puppetry have to be rediscovered?) played a vital role in the process of rebirth and renewal that eventually developed into Modernist drama and from there into the Avant-Garde... The rest (as they say) is history.

The rediscovery of puppetry played a vital role in the process of rebirth that eventually developed into Modernist drama...

As I have suggested above, the role that the puppet has played in the development of the theatre and of dramatic literature is easily underestimated. The dramatic imaginations of such theatrical heavyweights as Goethe, Kleist, Büchner, Wedekind, Maeterlinck, Jarry, Cocteau and Lorca were all profoundly influenced by their interest in, even fascination for puppetry. Goethe was given a puppet theatre at the age of twelve and it had a profound effect on his dramatic vision. Through its nurturing and shaping of the creative imagination of so many important artists, this seminal artform can legitimately claim to have had a decisive influence on the development of 20th century theatre.

But what of the development of a theatre for the 21st century? Is it possible to see a familiar pattern emerging? Is the dominance of ‘traditional’ drama theatre again being challenged? There can be little doubt that puppetry (live animation, object theatre – call it what you will) is once again fascinating many of today's most innovative theatre artists. The recent work of companies such as Improbable (Shockheaded Peter) and Complicite (Light) – to name just two – provide evidence of this. Artists are, once more, deliberately blurring the boundaries between performance disciplines and other means of artistic expression; therefore, we should not be surprised that once again the puppet is being embraced by a range of influential theatre artists. Practitioners such as Robert Lepage, Robert Wilson and Ariane Mnouchkine have regularly incorporated puppetry as a vital component within their work. Although naturally puppetry has thrived as an integral part of some of the most imaginative children's theatre, now it has again found an adult audience who welcome it as a major and magnetic force within the vanguard of contemporary theatre practice.

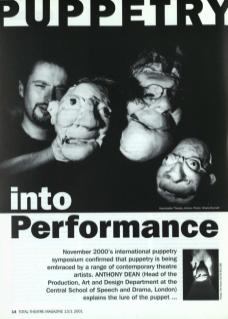

This awareness that more and more theatre companies are incorporating puppetry as a significant element within their work prompted the Central School of Speech and Drama (in association with Total Theatre Network) to organise the symposium Puppetry into Performance: A User's Guide. At the symposium, and within the pages of the subsequent publication, a very strong sense of the acceptance of puppetry within the broader context of performance emerged, with an increasing number of companies and theatre artists now taking it for granted as a vital component of their work. It seemed possible to agree that puppetry, once again, was welcome to take its place on the ‘theatrical stage'.

My own enthusiasm for puppetry was inspired by the work of companies like Theatre DRAK of Eastern Bohemia and the Philippe Genty Company. What impressed me most about these companies is that they were simply making great theatre, using every theatrical means at their disposal – but with a clear emphasis on the animation of objects, material and figures. DRAK's production of Pinocchio was staged with numerous performers and one puppet, while the performances devised by Genty filled huge stages with light, movement and the magical and mysterious manipulation of materials.

Faced with work of this kind from some of the most interesting theatre-makers – directors and scenographers – in the field, one is obliged to review and reassess received ideas about puppetry as being of a specialised, and therefore by definition limiting, form unfit to share the 'legitimate' stage with the actor. Today these ideas seem old-fashioned and their purveyors out of touch with the zeitgeist of contemporary performance practice.

The symposium and the subsequent publication provided an opportunity for practitioners who are incorporating puppetry and object animation into their work to share with the wider theatre and academic community their creative rationale and working methods, drawing together views on this topic from a range of contemporary practice for the first time. The symposium was held at the Theatre Museum on 27 November 2000 and was mounted jointly by Central's Production, Art and Design Department, the Theatre Museum, Total Theatre Network and the Puppet Centre Trust.

Contributors to the symposium included Duccio Bellug Vannuccini (Théâtre du Soleil). Clive Mendus (Theatre de Complicite). Sue Buckmaster (Theatre-rites) as well as Julian Crouch and Phelim McDermott (Improbable Theatre). In addition to these contributors, Lucy Neal, co-founder of the London International Festival of Theatre (LIFT) acted as chairperson to the presentations and discussions on the day. The symposium drew together approximately a hundred delegates drawn from the contemporary performing arts sector across the UK.

The publication associated with the symposium, Puppetry into Performance: A User's Guide, is available at £5 per copy.