Beccy Smith sees Me, Mother at Circusfest, prompting a reflection on new adventures in motherhood and the arts

It was in a theatre that my experience of motherhood finally began, after two days solid of warm-up acts. An operating theatre, sure, but an environment whose concentrated gaze, lights, transformations and undeniable drama were qualities that felt recognisable, through the epidural haze, from my professional work. I’ve been a theatre maker for nearly 15 years and a mother for just one, yet it’s fascinating and challenging to discover just how mutually exclusive these creative acts, which share so much common ground, are seen to be. Culturally, I was struck after giving birth by the paucity of representation or discussion of this process and of the lived reality of motherhood in novels, film and the visual arts (an ellipsis that must contribute to some of the fascination exerted by shows like One Born Every Minute). In theatre, the challenges of creating work in this evening-centred industry are practical as well as cultural. Yet by missing out the experiences of mothers in the theatre, we are denying audiences as well as artists. There are a growing number of practitioners starting to focus on redressing the balance.

Matilda Leyser

Since 2014 when her son was two, aerialist and trapeze artist Matlida Leyser has been holding Open Space (following the Devoted and Disgruntled model, a company with whom she is associate director) meetings for mothers and carers of small children who are also attempting to sustain a creative practice. These go under the name Mothers who Make.

Issues arising at the meetings highlight both the very real practical (financial and time) issues in which this problem is steeped and the significant emotional issues faced by highly creative and competent people, mostly women, who face crises of meaning and identity when unable to pursue their established careers due to motherhood. Through the meetings, which initially ran over the course of a year hosted by BAC, a clear need was articulated whose momentum has followed through into satellite groups being set up in other cities around the country as well as the launch of a national campaign – Parents in Performing Arts [http://www.pipacampaign.com/] – launched last October. This initiative is supported by industry-wide partnerships and spearheaded by inclusive theatre company Prams in the Hall. So far it’s been a conversation and a campaign, but now Leyser has placed the subject creatively centrestage in the first stages of a new production called Me, Mother which brings these experiences vividly to life whilst itself acting as a demonstration of the rich contributions mothers (of course!) still have to offer the industry.

As a practice, circus feels like it sits (or flies? Swings!) at the more extreme end of antithesis with motherhood: at the form’s heart are physical feats which no pregnant woman would (we imagine) risk, and which no soft mother’s body could achieve. Yet of course circus artists get pregnant and of course, after becoming mothers, undergoing that great transformation, they remain themselves – practitioners who need to work and artists with the skill to express in this form.

Me, Mother: Marianna De Sanctis and her daughter Mae Lestage

In Me, Mother this dichotomy is placed at the core of the performance. Five circus performers, four of them mothers and the fifth with motherhood on her mind, share deeply personal stories, scientific and historic fact about birth and motherhood, whilst populating the compact stage of the Roundhouse Studio with an array of circus equipment and lo-fi performance (casual slack rope walks; exercise routines on the trapeze). The performance has been created after just a week working together in a room, sometime with their children present, and its contingent quality is reinforced by the scratch score created and mixed live by musician Elizabeth Westcott. The improvisatory elements of the show, which moves through a handwritten structure Leyser has pinned to the wall, also serves a dramaturgical point – mothering creativity is often snatched and solutions (in both art and parenting) determined by the available space and time, or made up on the spot. This kind of open dramaturgy, where artists support one another and reach mutual decisions live about what is to be shared and how, feels inclusive and non-hierachical. It is at its clearest in the opening sequence, where the performers vie to share illustrative stories about one another. Leyser and her company create a very warm, generous atmosphere in which their stories can be shared which create a community with the audience – they are there with us not for us.

There are times when this quality can also feel too loose. As seen on its opening night, there were moments of too much tentativeness which distracted – energy dropped. Moments of potential felt suddenly stifled by a lack of follow-through which limited some of the transformative possibilities of the inspiring acts and stories on display. The hour-long performance is prefaced with an installation sharing interviews recorded with these and other circus mothers about their experiences. It’s an inclusive opener to frame the field (and also to situate the performance in the context of the wider research project of which it forms part), but in juxtasposition with the show, it is a reminder of how statistics and anecdotes are no stand-in for the artistry and vulnerability of live performance. There are magic moments in this show, and they live largely in the powerfully crafted stories shared by some of the performers – of birth, of pregnancy and of returning to work. There’s still more to discover about how to incorporate this content to the circus forms its discusses rather than placing them alongside one another (hardly surprising after just a week’s work), but nevertheless, when the transformations occur the crafted storytelling of human experience holds us in a powerful moment of connection and in these moments we see how art paradoxically transcend the artist’s immediate circumstance as well as being viscerally empowered by it. Of course there are some battles for which we need politics – affordable childcare, the possibility for flexible working (although as I found out when producing the all-female team of Three Generations of Women recently, simply agreeing set finishing times, and sticking to them, made a world of difference) but, when it works, it is the art itself that offers everyone a deeper imaginative understanding of just why this is all worth fighting for.

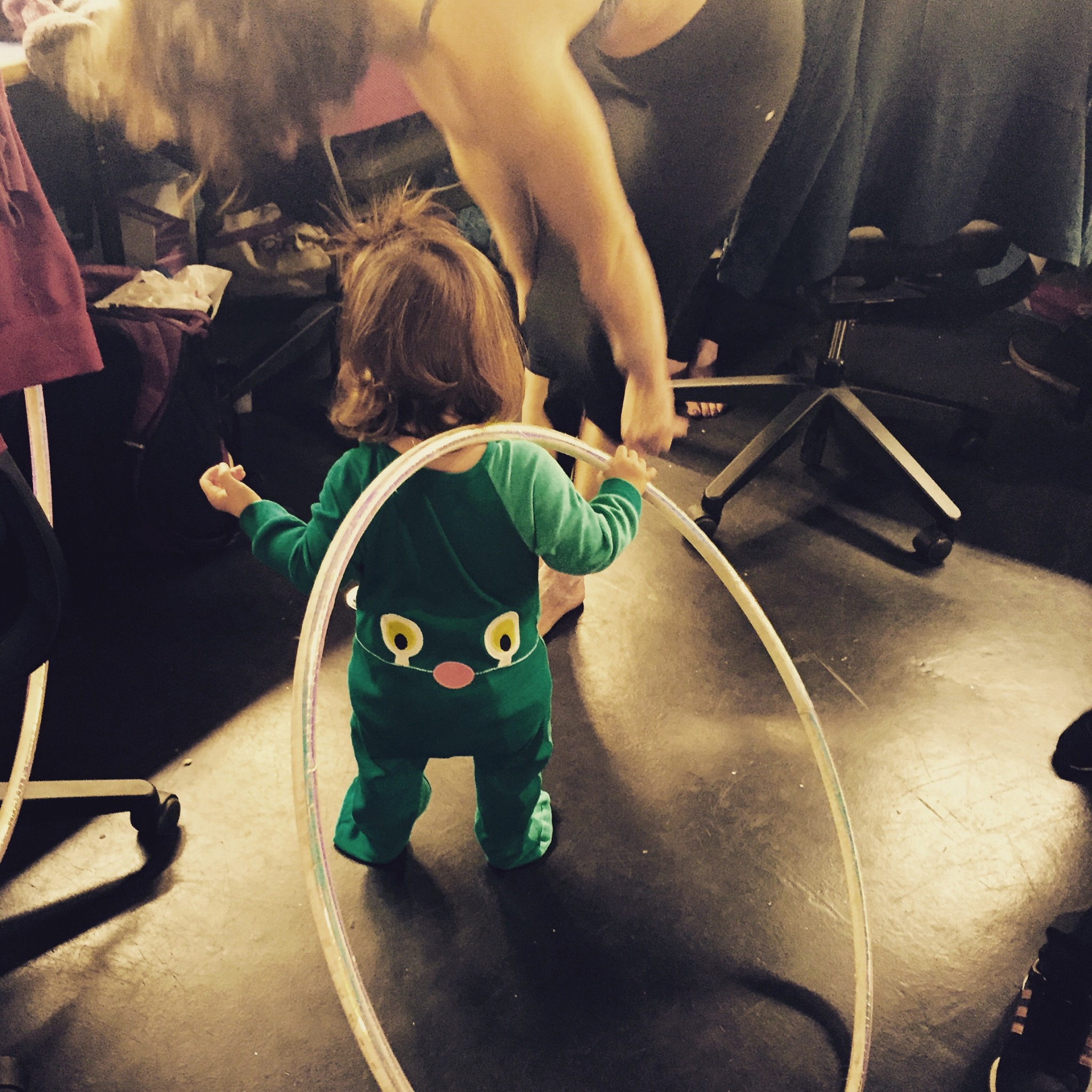

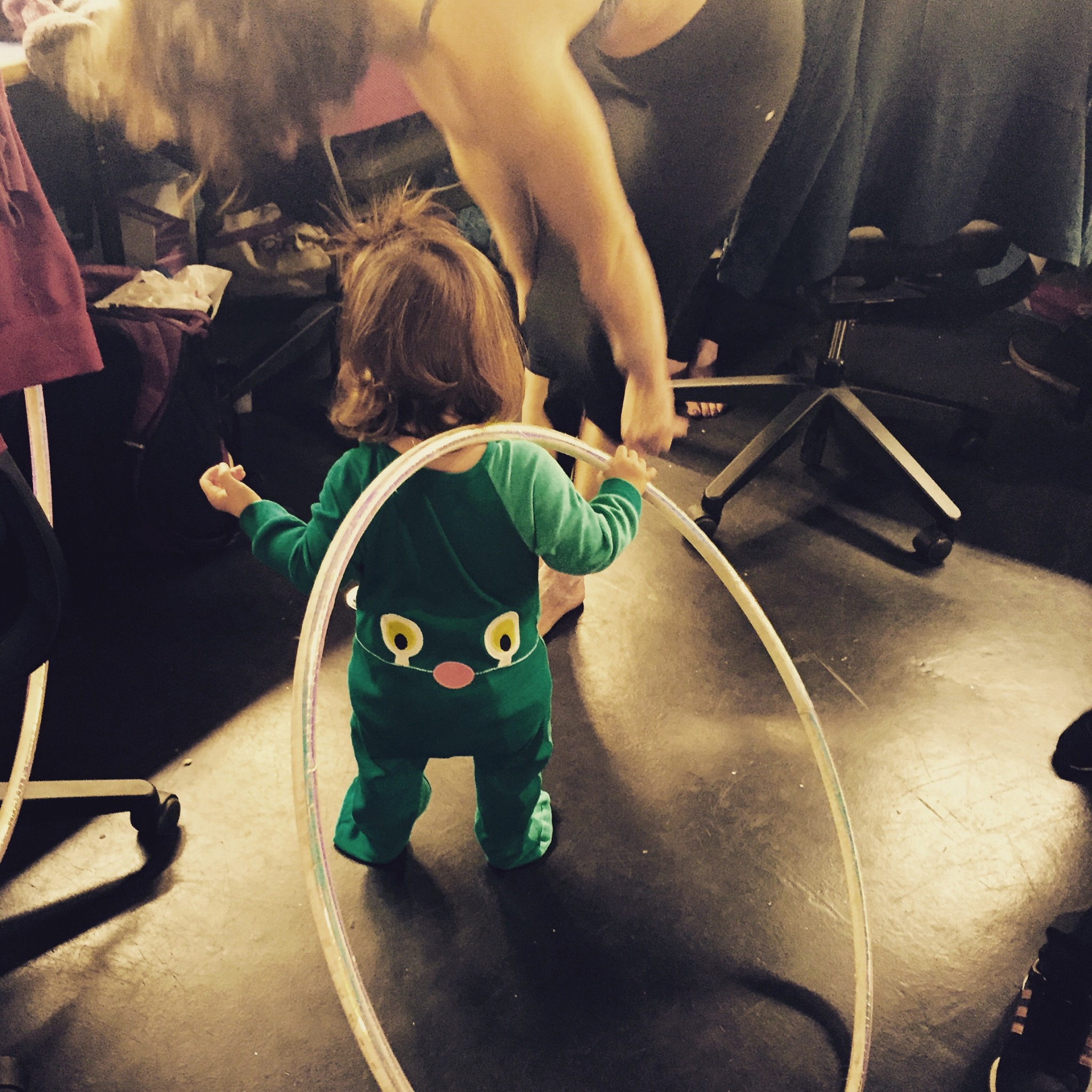

Me, Mother: mother and baby rehearsals

Another artist interested in fully incorporating the experience of motherhood to creative practice is Duska Radosavljeviḉ through her Mums and Babies Ensemble – a manual for which was published with the support of the Arts and Humanities Research Council (AHRC) last year. The idea of the Ensemble is quietly revolutionary – to look for models that allow the incorporation of babies to the rehearsal room, not as problems to be solved but as creative contributors to a piece of work. The inclusive ethos underpinning the idea underpins a publication that aims to disseminate the practice by acting as template for other theatre parents to create their own versions of the experiment. Structured as a list of ingredient components, the books offers plenty of very straightforward, practical problem-solving devising suggestions (A table which illustrates, ’this is what you will plan to happen, and this is what is likely to actually happen,’ for example). This sort of approach begins to broaden out the publication’s relevance: here we find not only useful sensibility for the recreation of the process, but helpful attitudinal understanding about devising in general, and parenting too. And once again I am struck by the relevance and connectedness of parenthood and creativity. I now feel confident that my creative vision as a dramaturg and writer has expanded and nuanced as a result of the experience and continues to grow. I am more honest, more dynamic with my time. The question remains, though, will I be supported in the capacity to turn this new potential into work?

Of course the problems discussed here are not reserved for the theatre industry: parents of every ilk face profound challenges and difficult decisions about how to combine necessary work and/or meaningful careers when attempting to integrate with them raising children. Yet it is arguable that the representation of mothers as makers and the portrayal of the parenting experience within our cultural conversations is an essential step in making the case for the political work that needs to follow. Because when mothering and art are rendered mutually exclusive the vital realities of these experiences are made invisible; and what’s more, as well as undermining legions of inspiring and talented women, our cultural life becomes poorer and less representative by this exclusion.

MES: Me, Mother, directed by Matilda Leyser., was presented in Circusfest at Roundhouse, 21 April–23 April 2016. It was seen by Beccy Smith on 21 April 2016.

The Mums & Babies Ensemble: A Manual, written by Duška Radosavljević, Annie Rigby, Lena Šimić and babies Joakim, Nina and James, is published by the Institute for theArt and Practice of Dissent at Home, Liverpool, 2015, and can be purchased online from Unbound http://www.thisisunbound.co.uk/products/the-mums-and-babies-ensemble-a-manual

See also The Mother by Dorothy Max Prior, published on Total Theatre Explores: http://totaltheatre.org.uk/explores/reflections/mother.html

The Total Theatre Explores research project was undertaken between 2003-2005. The Explores legacy lives on in its dedicated website, hosted within the Total Theatre site, which is intended as a permanent resource set up to celebrate the work of women practitioners of physical and visual performance, give insight into a diverse range of working practices by women artists, and provide information of use to anyone interested in women working within physical and visual performance.

See www.totaltheatre.org.uk/explores

Packed into the Warren’s smallest studio are signs of organic life. A tree’s branches reach up toward the rig and from the floor wild grasses are sprouting. It’s a relief to enter this world as we pile in from the busy playground of the Warren’s ambitious, astroturfed Edinburgh-style courtyard. The carefully crafted set whose materials do seem drawn from nature, the sighs of the wind and birdsong, seem to conjure up breathing space amongst this hubbub. The young audience (the show is for children aged from just three) are immediately entranced.

Packed into the Warren’s smallest studio are signs of organic life. A tree’s branches reach up toward the rig and from the floor wild grasses are sprouting. It’s a relief to enter this world as we pile in from the busy playground of the Warren’s ambitious, astroturfed Edinburgh-style courtyard. The carefully crafted set whose materials do seem drawn from nature, the sighs of the wind and birdsong, seem to conjure up breathing space amongst this hubbub. The young audience (the show is for children aged from just three) are immediately entranced.