The title of this blog is a quote – or misquote, or paraphrase perhaps – from Liz Aggiss’s new work-in-progress The English Channel, an excerpt of which was presented 9 April at the Brighton Dome’s new venture The Works. (And where do I know that name from? Ah yes it was the title of a soon-to-be-revived series of features in Total Theatre. But we won’t complain, imitation being the sincerest form of flattery.)

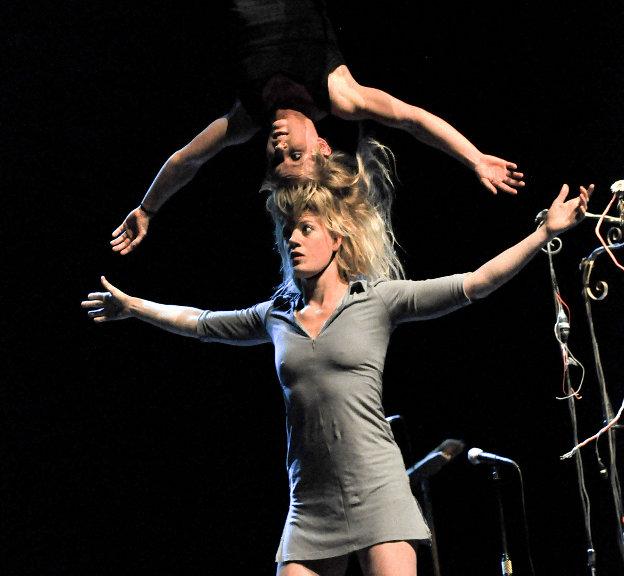

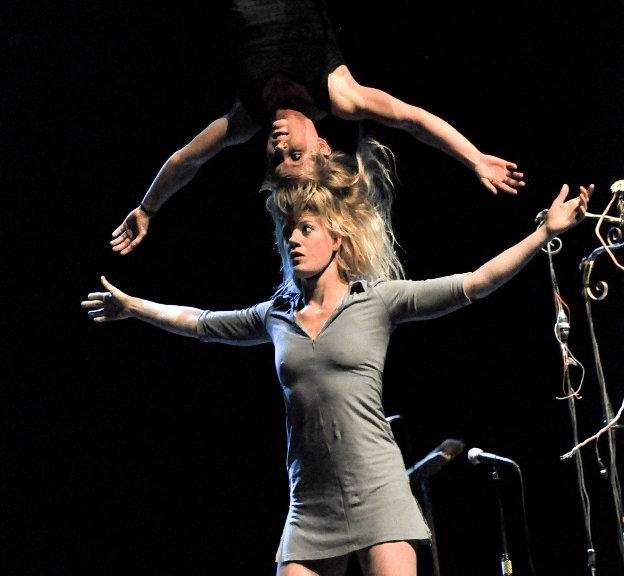

Anyway, back to Liz. There she is in all her glittery green glory, standing before us with hips a twitchin’ and a goblin grin on her face. ‘Do I please you, or do I please myself?’ she asks. It’s a statement that is at the core of an artistic investigation into the nature of performance, and of being a performer – and in particular of being a female performer age 60, who has long past the stage in her life or her career when she has to bother too much about what others think. And yet of course you never stop being bothered – never stop trying to please, never stop giving them what they want. That’s what performing is all about, isn’t it? That’s what being a woman is all about, isn’t it? ‘I’m a one-woman variety show’ says Liz as she takes her seat for the after-show discussion.

But the question raised in Liz’s piece – who this is actually for, the artist or the audience, who is pleasing whom? – is a pertinent one for the whole evening.

The latest new night of new work to hit Brighton, The Works is an open evening, advertised publicly, ticketed but free, in which works-in-progress are presented by three artists or companies at various stages of their career. But why? Who is it for? What are the expectations of both artist and audience?

I’ll admit straight away that I’ve developed a mistrust, steadily growing over the past decade or so, of Scratch nights and work-in-progress showings. There is an irony here, as without blowing my own horn too loudly, I did play a part in establishing this now-commonplace theatrical activity, so perhaps have only myself to blame. In the late 1990s, as director of an artists’ forum called Bodily Functions (yes I know – I didn’t choose the name), I set up something called Platform at the Komedia Theatre – a twice-yearly space for artists working in physical, visual and devised theatre / live art performance to present the beginnings of their ideas to a (hopefully) receptive audience. One of our production assistants was one Louise Blackwell, who then left Brighton to work at BAC in London, and subsequently coin the term Scratch nights, using a similar format to the Platform at the Komedia: a number of 10–15 minute acts; feedback forms to pass comment on work seen; and the chance to chat to the artists informally in the bar afterwards.

What we found with Platform was that even educated audiences often found it hard to really understand how to receive the work. ‘Most of the things I saw were not really developed’ said our then Arts Council officer in response (and ACE hadn’t even funded this particular part of our work, to add insult to injury). Er yes, it is unfinished work so it is not yet developed – that’s the point… But actually, is it fair to present snatches of unfinished work to an audience and expect them to understand? Can it do the artist more harm than good to present their yet-to-incubate musings in public? Maybe it’s a personal thing, but I know that when I’m developing work I often hold it close to my heart for a very long time, not even letting close family and friends in on it. Yet theatre is an artform in which the artist’s relationship to the audience is at the heart of the matter, so they have to be let in at some point. There are some venues / organisations who have worked hard to improve the scratch format: the Nightingale Theatre, for example, structures their evenings very well, with the post-show feedback set up as small roundtable discussion groups, audience members free to flow round to whichever artists’ tables they would like to join. I’m still wary of scratch evenings, but theirs is better than most.

The Works was work-in-progress excerpts rather than scratching new ideas, I suppose I should make that clear – and the three pieces shown were at very different stages of development. Liz Aggiss, I suspect, wouldn’t go anywhere near an audience until she’d put in a lot of legwork and was reasonably sure of where she was going and what she was attempting to achieve. Her excerpt from The English Channel was the very necessary stepping out from the solitary space of the rehearsal studio into the engagement with audience that is necessary for something to become a real piece of performance work. It was very new, very fresh, finding its way – but it was clear about what it was and where it was heading, and was thus immensely entertaining and thought-provoking.

So I’m fine with the idea of seeing work that is in progress, once progress has been made – I think there is a value in presenting early versions of newly created shows, and for artists to then rework them as a result of trying out before an audience, but that’s different to this bitty ‘a taste of this and a slice of that and tell us what you think’ approach. I’ll confess that I didn’t read the publicity properly and I thought I was just going along to see an early version of Liz’s show, so when I found out I was in for a two-hour marathon – three excerpts from three very different works, plus this rather formal discussion process after each one – I got a bit sulky!

Also to say that another gripe against the pot-pourri approach is that I feel unsure how to respond to something when I’m only privy to part of the picture. To just get 15 or 20 minutes of what will be a full-length show, then to be asked what we’ve seen and understood, is inevitably encouraging discussion along the lines of ‘I didn’t understand this’ or ‘’you need to make that clearer’. It’s like being in a writers’ workshop and reading out chapter four of your novel-in-progress and someone saying,‘Well, you’ll need to make that clearer, I didn’t understand what that character was doing’. Well of course you didn’t – I’ve just read you chapter four and you haven’t read chapters one, two or three, have you? How can you possibly understand?

But the aspect of the evening I had most problems with was the feedback format. The pieces were presented to a large audience in a formal theatre setting, with the feedback session after each one set up like a regular post-show discussion – i.e. with the artist or company and facilitator (director/dramaturg Lou Cope) sat on chairs facing the audience, who are then led into the discussion with pre-decided questions about the work, followed by some open/general discussion. To give Lou her due, she did start the evening by reminding the audience that this ‘wasn’t about them’ and that questions or comments made should be precise and to the point and relate directly to the work seen – but of course that didn’t happen. Instead we had the usual post-show horrors: the awkward silences as people try to think up answers to the questions thrown out to them; the gushers who can’t stop telling the artist how wonderful she is (and that’s helpful to the making of the new work? I don’t think so); the ‘maybe you could do it this way instead’ problem-solvers; and the ‘I haven’t really got an opinion about any of it but I feel the need to say something, and say it at length’ ramblers. Perhaps some people find this useful, but it just felt strained and uncomfortable to me. Both artists and audience were placed in the spotlight (literally and metaphorically) and when on the spot didn’t necessarily talk much sense. I tend to feel that just presenting the work to an audience is enough for the artist, who can then form their own opinion of what worked and what didn’t. Do it in front of people and you can feel when something sinks sadly into the ground or when something is a genius moment of inspiration – you don’t need a post-show discussion to tell you.

In many ways, this new venture feels like an audience development initiative disguised as something else. ‘Do give us your email addresses so we can tell you when these shows are on’ being an obvious give-away. As a friend of mine said, if that is what it is, let’s be upfront about it, rather than pretending it’s there to help the artist make the work. I dislike the pretence that it is useful to get the audience engaged with the dramaturgical process of making a show. In my humble opinion, that’s the artist’s job.