Epiphany! So the Three Kings have come and gone, the Christmas trees have been taken down, and the Twelfth Night revellers have sobered up. The world is no longer turned upside down – everything’s back in its rightful place. It’s back to work, then…

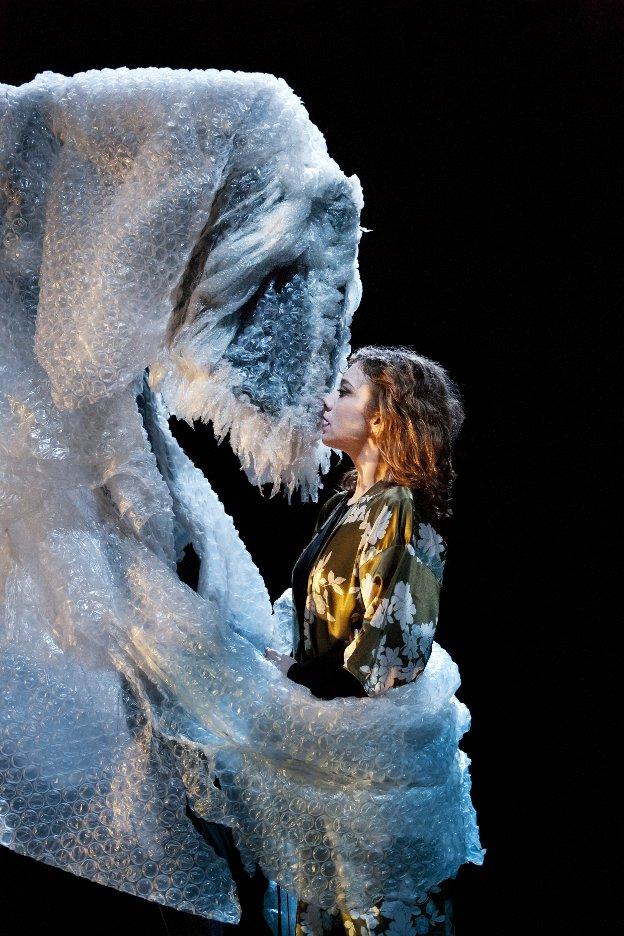

Except of course that for many working in theatreland, the Christmas hols are hardly a holiday – what with pantos, puppetry shows and various Christmas residencies. A few names to drop for their seasonal successes are the Total Theatre Award winning 1927, whose The Animals and Children Took to the Streets did a run at the National Theatre that was sold out almost from the moment it was announced; the Little Angel Theatre’s collaboration with Kneehigh, The Very Old Man with Enormous Wings (profiled on Radio 4’s Frontrow special on puppetry); Theatre-Rites latest collaboration with Arthur Pita, Mojo, at the Barbican; NIE”s Hansel and Gretel at The Junction, Cambridge; and Travelling Light’s Cinderella at The Tobacco Factory Theatre in Bristol. At least some of which are reviewed here…

The New Year kicked off with the usual nationwide extravaganzas of fireworks displays, parades and parties – keeping many of our Total Theatre friends and associates (street theatre artists, circus and cabaret performers, pyrotechnicians) in employment.

At the stroke of midnight, I was to be found at the Komedia in Brighton for Trailer Trash – a regular bi-monthly ‘participatory event’ which features live performance, film and music inspired by one particular film or cinema genre. So, a bit like Secret Cinema except, er, not secret – they advertise the theme and the audience dresses appropriately.

Previous evenings had been dedicated to David Lynch, Baz Luhrmann and Barbarella. For the New Year’s Eve special – sold out well in advance, with many Trailer Trash ‘first-timers’ in addition to the hardcore regulars– they played it a little safer and more generic and went for a Las Vegas theme. So, yes, inspiration galore there: Honeymoon in Vegas (there was a Vegas chapel-of-love set up for anyone feeling the need), Leaving Las Vegas (plenty of broody Nic Cage look-alikes on stage and in the audience), Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas (there were a good few gonzo journalists around the place). Elvis Presley’s Viva Las Vegas and the James Bond Diamonds Are Forever provided swinging inspiration for the house band, whose lead singer Laura Wright started the night in a gorgeous metallic gold dress and headdress, and ended the night in nothing more than red frilly knickers and a pair of star-shaped pasties. There were plenty of Showgirls, including the saucy burlesque dancer Coco Deville, who is lovely to watch as she always seems to be enjoying herself onstage so much – and I hear that I missed a troupe of feathery fan dancers earlier in the eve. The Ocean’s Eleven bodged heist scene informed a cleverly convoluted doubles corde lisse act by Trailer Trash co-founder Kitty Peels and her aerial partner Milo, their twists and turns, tumbles and tangles echoing the hitches and hiccups of the plot, the routine culminating in a hasty descent to the ground as they (and we – this act is performed in the middle of the dancefloor, not onstage) are showered by a paper money from a bursting bag.

Just a few days later I find myself at the Royal Albert Hall for Cirque du Soleil’s latest, Totem – back for a second year. It is directed by fellow Quebcois artist Robert Lepage, which might give one hope of something with a little more edge than usual – but I found it hard to discern the Lepage influence on the production. But if we put aside any expectations of what Lepage might bring, and focus on the circus itself, it delivered some very good acts (as you’d expect!) and thus an enjoyable enough evening. See review here…

Next up for me this January will be the annual London International Mime Festival who this year (as ever) are presenting a must-see programme of physical and visual theatre work, from the UK and from around the world. UK companies to look out for include No Fit State, and Sugar Beast Circus, who come to Jacksons Lane (making its debut in 2012 as a LIMF venue!).

Total Theatre strongly recommends Gandini Juggling’s Smashed (as featured on the cover of the current issue of the magazine, subject of The Works by Thomas Wilson), and I can also personally recommend Translunar Paradise (playing at the Barbican) by Theatre Ad Infinitum, a story about ‘life, death and enduring love’ that took the Edinburgh Fringe 2011 by storm. It was shortlisted for a Total Theatre Award and I described it in my Edinburgh Fringe reviewhere as ‘A near-perfect example of contemporary wordless theatre’.

I’ll be chairing two of the festival’s post-show discussions. First for Blind Summit’s The Table which comes to London hot on the heels of a phenomenal success at the Edinburgh Festival Fringe, where it won a Fringe First, a batch of rave reviews, and a packed house throughout its run. The show opens the 2012 festival at Soho Theatre, a new venue for LIMF. The post-show is on Monday 16 January.

Then I’ll be at the Roundhouse on the following night, Tuesday 17 January, with Invisible Thread, the company formed by Liz Walker from the ashes of Faulty Optic. They appeared previously at LIMF with a three-part work-in-progress called Fish, Clay, Perspex and here return with their first fully-fledged full-length show, Plucked.

I am also planning on a trip to the Southbank Centre to see Toron Blues corde lisse piece Tendre Suie, inspired by Jean-Paul Sartre’s Huis Clos, which explores the notion that ‘hell is other people’. (Ah, so perhaps a doubles aerial act that isn’t about romance?); Australian company Fleur Elise Noble with 2 Dimensional Life of Her, a work of ‘light and shadows’ that uses drawing, animation, puppetry, projection, and paper, presented at the Barbican’s Silk Street Theatre; and also at the Barbican, Camille Boitel’s L’Immédiat: ‘On a stage crammed with machinery, objects, junk and bric-a-brac of every kind… a tumultuous, visual commentary on the uncertainty and mayhem of modern times’.

The London International Mime Festival runs 11 – 29 January 2012. For information on all the above shows and more, see www.mimefest.co.uk For venue details and online bookings, see here.

Perhaps I’ll bump into some of you at one or other of the above.

Happy New Year!