Circa’s mission statement boldly claims that they have ‘created a boutique contemporary artform from the traditional languages of circus’, suggesting that contemporary circus prefers to preserve its traditional forms rather than seek new pathways or modernise its media. Their route to this ‘new frontier’ in circus arts is through a refocusing on the human body, which, they say, is ‘emotionally connected, spiritually resonant, and deeply affecting’. Cirque du Soleil this is not, but there are, these days, many companies who succeed in exploring a more ‘human’ ground somewhere between the sequins ‘n’ sawdust of the old and the polish and finesse of the ‘new’ circus. The Seven Fingers, Cirkus Cirkör, Cirque Éloize and the Thiérrée family, for example, have all demonstrated rethinkings of traditional circus disciplines, new combinations of art forms, and, frequently, a preoccupation with identity.

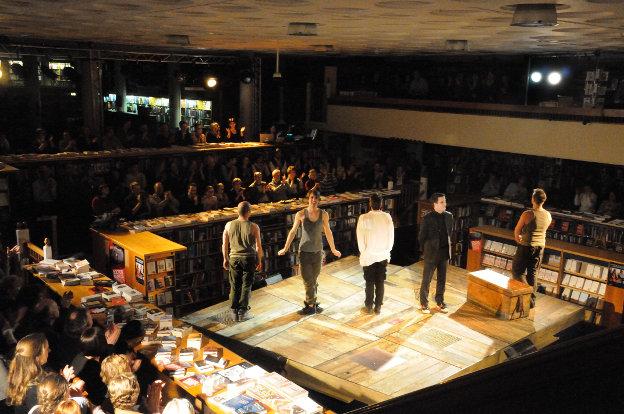

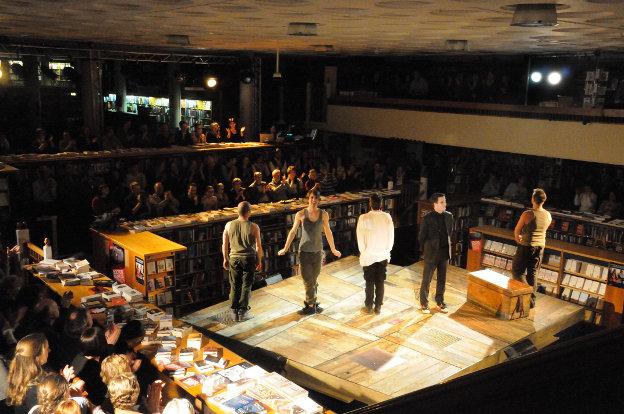

This is not to say that Circa’s work is not different. Wunderkammer does very literally focus on the human body. The overall impression of this seven-strong company is that they are very muscly indeed. The women are small, solid and rippling with power, the men poised, sculpted and graceful. Wearing matching spangly underwear, reminiscent of traditional circus costuming but unflatteringly accentuating every muscle, every solid line, the company are coldly lit by LED wands placed around the empty stage. The performance is incredibly athletic – the company endlessly balance, dance, throw and catch each other, climbing, swinging and moving amongst each other. They push themselves, performing carefully chaotic and haphazard-seeming routines that appear to be right on the edge of their abilities. This is not the gasp-a-minute, otherworldly fantasy of Cirque du Soleil – these are real, very physical bodies, right here now.

A possible drawback of playing in the Wales Millennium Centre and other large-scale venues is the vastness – there are several moments early on that are lost through a lack of intimacy. A girl with bright red lipstick, red hair and black and red bikini can move her mouth and eyebrows in such a way that they seem to be moving all over her face. A boy in pants and a penguin-like shirt-front stuffs an uninflated balloon up his nose. Even when the whole company get together and stuffs balloons up their noses, it’s difficult to react. The artists are too far away for us to connect with them and understand what’s going on. The loss of these few ‘intimate’ moments doesn’t help with my feeling that Circa are going out of their way to make their artists appear interchangeable, emotionless, sexless even. I start recognising them only by their hair. The occasional moments of humour – for example a female contortionist, who creates her own backing track by humming into a microphone held between her toes, which are suspended over her head – are entirely physical. A talented but unmemorable handbalancing artist performs on bricks: another artist moves each brick as she takes her hand from it; she is suspended for a moment, unable to go anywhere but where her uncommunicative colleague leads her. They don’t look at us, or each other, or express anything – their movements are neutral. This impersonality sits uneasily with the fact that it is created by such specific physical situations. I don’t get it.

Wunderkammer translates as Cabinet of Curiosities (where the Cabinet was a room of some kind – so the traditional cabinet of curiosities could be regarded as a physical collection of paraphernalia), an odd description for an unlocated show, performed as it is on this blank stage, leaving nothing behind. Though there are ‘freakshow’ type elements to the routines (à la La Clique), the expression of greater personality might help this make a real mark.Wunderkammer does showcase a great, and curious, range of acrobatic skills, with all the strength, bravery and daring that you’d expect in a traditional circus format, actually – but their choice not to replace the excised lustre of the traditional circus ring, the bright lights, the merry music, with an emotional connection, a spiritual resonance, left me without anything to connect with.