What’s Become of You? is the seventh of Compagnie 111’s works to be presented at LIMF, and is, as artistic director Aurelian Bory notes, something of a departure from his usual work. Bory describes this as a portrait of flamenco dancer Stéphanie Fuster, and herein lies the key difference between C111’s usual work and this new piece.

What’s Become of You? is the seventh of Compagnie 111’s works to be presented at LIMF, and is, as artistic director Aurelian Bory notes, something of a departure from his usual work. Bory describes this as a portrait of flamenco dancer Stéphanie Fuster, and herein lies the key difference between C111’s usual work and this new piece.

Previously Bory’s works have been visual and kinetic sculptural landscapes, carefully constructed in form and content to reach out and fill space. So in the striking Plus Ou Moins L’infini acrobatic figures traversed the mise en scene in elegant poses, and in the arresting human and robot dance of Sans Objet the set was dismantled and reconfigured into new architectural forms. But with this portrait of Fuster, Bory has shifted his concerns from external, physical space into interior, emotional spaces. Thus Questcequetudeviens? is a piece about subterranean depth, rather than a landscape’s horizontality.

The work opens though on the surface of Fuster’s world. She emerges in classical flamenco dress, the bold red illuminated in the context of a stark set. As she slowly walks, skimming the surface of the stage, the dress detaches. In usual Bory style though it is not discarded, and instead, retaining its shape, finds its own life as a surface for Fuster to move with. It shrinks and grows, and submerges her. Finally it transforms into a majestic hat – a crown of rich fabric on top of the stocking-clad Fuster – before returning to its previous life as a dress and exiting of its own accord, leaving Fuster alone and exposed.

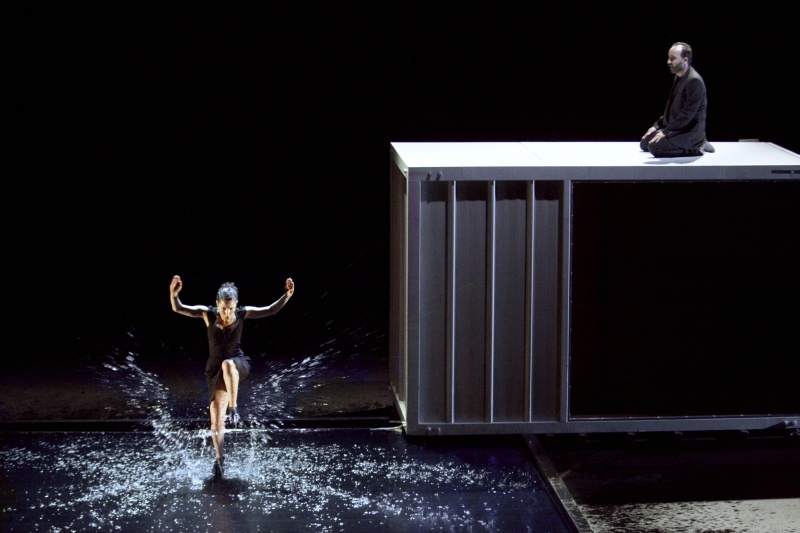

The second phase of the piece delves a little deeper, this time into the graft of flamenco training. Fuster, inside what looks like a steel shipping container with a glass wall, strikes poses and pounds the floor with a rising intensity. As she does so the glass begins to mist and her body appears to slowly dissolve. There are echoes of a caterpillar’s transmogrification, as Fuster’s driving energy and grey clothing begin to disappear behind the opaque surface. Alongside this José Sanchez’s deft guitar playing provides sporadic punctuations of rhythm and Alberto Garcia’s rich singing drifts melodically around Fuster’s form. Here is the play of different levels of being inside. Fuster is physically bound inside both the container and flamenco’s form, suggesting the ways in which both dancing and immersion in another culture can begin to mould and shape someone.

The final phase of the portrait sees Fuster emerge into the external world, this time clad in a black dress, to take her place on the same surface as she began. As she stands the surface begins to fill with water, as if the steam and heat of her training now find themselves condensing. This water then becomes the third surface of the piece. Though, rather than becoming a surface that obscures and hides Fuster, it is one that is fractured and punctured by her dancing. This time her steps are wider and slower in rhythm, though not less in intensity. As she slams her feet into the water-covered floor, the droplets of water arcing upwards and coating her inclined body, Fuster breaks her own reflection. In this the transformation is complete – Fuster has reached a kind of earthy transcendence of her previous superficial form. Now she moves, strengthened and refined internally and externally. In a final, if rather obvious, capitulation Fuster ends prone in the water, arms sporadically washing the water away from her body. Like a dying butterfly, partially unaware of her own demise.

Where before Bory’s work has always felt majestically airy, rising upwards, in merging the earthy and the numinous Bory has found a new register and grounded quality to his work. And though the last ten minutes of Questcequetudeviens? lack the same drive as the preceding 50 minutes, there is something transcendent in his fusion of the two poles of the vertical.