The future will be confusing. This is how it ends – there are no answers, no conflict resolution. In this, it could perhaps be argued that Chris Goode’s latest work, Weaklings, is less a piece of theatre than a multi-artform installation of texts, sounds and images, inhabited by four performers who activate the space. But that wouldn’t be telling the whole truth, because Weaklings is brilliant, beautiful, and dramaturgically sound, theatre. A play, you could say, that playfully deconstructs the world of an interactive online space – writer Dennis Cooper’s Weaklings blog, a magnet for every outsider in the blogosphere – and somehow, marvellously, miraculously, reconstructs it on stage.

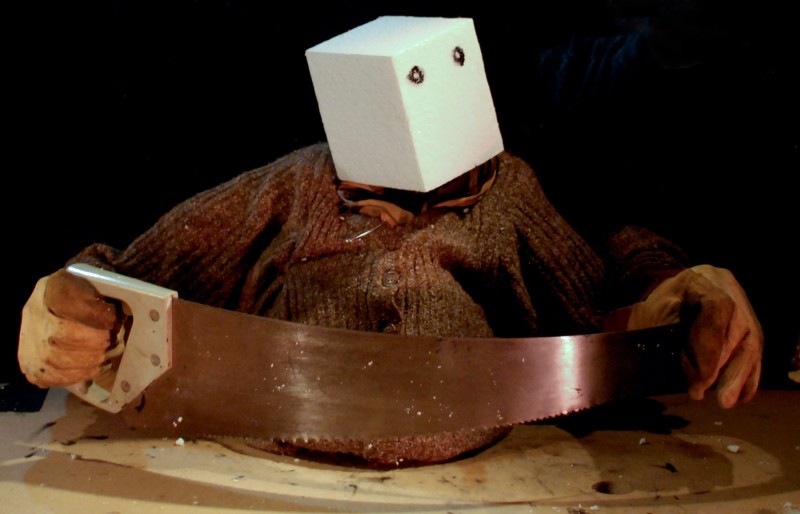

He takes everything we know about online space – the overload of information vying for our attention; the multitude of voices all speaking at once; the constant flow of images coming at us; the weird juxtaposition of cheery cartoon characters, pop videos, and porn all one click away from each other, whizzing past in fast succession; the mix of static and moving images; the interplay between text read and text heard; the anonymity and the exposure; the freedom to be whoever you want; the need to to be heard; the sharing and the shaming – and feeds it to us in a dazzling display of cut-ups and montages, all informed by a desire to move queer culture into revolutionary new territories. If William Burroughs and Brion Gysin were doing their thing now, this might be what they’d do.

The stage is set with an extended cage-like wire structure taking up a lot of the floor space, the site for the projection of texts, still images, and video. Three male performers move in, through, around, and in front of, this structure, sometimes alone, sometimes in relationship with each other. Their bodies (clothed or otherwise at varying points in the piece) become another site for the projections. There’s the intense intellectual one, played by Christopher Brett Bailey, who reads fast and furious tracts from his laptop. Nick Finnegan is blond and boyish, a picture of innocence, ripe for the taking. Craig Hamilton is a Joe Dellasandro for the modern age, flexing muscle, running, posing with hair falling into his face, a sullen come-on look in his eyes. Fantasies of bondage and rape, confessions of murder, harrowing tales of tormented childhoods, and heartbreaking pleas for love and understanding are played out by these three, augmented by onscreen contributions from actors and from real-life (whatever that might be) users of the Weaklings site (who contribute to the discussion forums using pseudonyms such as Tender Prey, Lost Child, and Atheist). My favourite is a very affable man called Thomas Moore, who I see as a portal or guide into the blog for uninitiated people like me.

Above all this, at a work station positioned on a kind of mezzanine level above the cage, is the actor playing Dennis Cooper himself. The instigator, the puppet master, the Deus ex Machina, the controller, the mediator. A reluctant god, we learn early on in the piece: he starts the blog at the request of his website visitors, having asked them what would most improve the site. A message board would be better, he grumbles, before devoting himself selflessly to the task of replying to every single comment with a religious devotion that takes up an enormous chunk of his life. As Dennis speaks, a large image of ‘his’ face is projected onto the front of the cage, so we see, simultaneously, the live and mediated image of the writer at work.

And here is the stroke of genius. Chris Goode has cast Karen Christopher (the enigmatic ex Goat Island performer) in the role. Having a woman – particularly such a talented and charismatic one – playing Dennis Cooper is perfect. In a show that is about mediation, about roleplay, about questioning what is ‘real’ and what is ‘fantasy’, this is just what is needed. Every time Karen speaks Dennis’ words, we are reminded that everything we see and hear – here on this stage, there on the internet, and elsewhere in the wider world – is only one version of reality. All life is a game, don’t take things at face value.

It is also great to have a strong female presence onstage throughout the piece – the easier decision would have been to have all-male casting, but that would make it something else, something less compelling. Inevitably, most of the site users are male – although we meet a couple of women onscreen. We also meet Dennis Cooper’s associate director Jennifer Tang, who confesses with complete honesty that as a ‘straight woman’ (her definition of herself), the site is not talking to her.

There are times when this reviewer also feels that she is meeting a world that is not hers. As I often have throughout my life, I find myself wondering why men get so hung up and obsessed by sex, which is (after all) only sex. And it is hard not to be disturbed by some of the extreme Slave and Master confessions regardless of whether they are pure fantasy or actually enacted in some way. In the post-show discussion, Chris Goode talks of Dennis Cooper as a ‘profoundly moral’ person, who again and again ‘stays with’ people in a vulnerable place, acting as a non-judgemental witness. This, I feel, is what Chris Goode has brought to the stage. He asks us to be non-judgemental witnesses, to be there for these often difficult and disturbing ideas and images.

Although occasionally alienated or disturbed (and that’s OK – these things are disturbing) I find myself drawn into a fantastical world of extraordinary and exciting words and images that jostle for my attention in the best possible way. Often, there is a beautiful contrast of speed and stillness between the projected texts and images, and the pictures created by the human bodies that stand frozen in the light, or move slowly and rhythmically in the space like living sculptures.

A word of praise here for designer Naomi Dawson, who has worked with Chris Goode to create a powerful scenography for the piece; and also for lighting designer Katharine Williams – the strong reds and blues, placed to the side and giving a suggestion of light from stained glass windows, and the sea of tiny red lights placed around the stage by Craig, suggest a sacred space. Original sound is by Scanner – although that is mashed in with clips, samples and soundbites galore.

This is the first outing for Weaklings, presented at Warwick Arts Centre (who co-commissioned it) as part of the Fierce Festival 2015. It is a technically complex work, and the performers all did a sterling job, working with the technology to create a cohesive whole. It could, perhaps, be slightly shorter, and there are a few odd lulls, and towards the end moments where it feels as if we are coming to an ending, then don’t. But this is all to be expected so early in the life of a show, particularly one as complex as this. Hippo World this ain’t…