It’s a Wednesday night in central Birmingham, and we’re heading to BOM (Birmingham Open Media), a venue and artists’ studio close to New Street station which is the designated hub for Fierce Festival 2015, a five-day bonanza of live art, experimental theatre, installations, screenings and parties. We pass old-school Chinese restaurants with red dragon signage; a gaggle of girls with bare legs and massively high heels who are cheerily falling out of a taxi; a pub with peeling purple paint offering a special Monday night beer and curry deal (on a Wednesday?) And here we are. A blue neon pin-up girl announces Adultworld, the ‘gentlemen’s club’ opposite, illuminating the small group of smokers in animated conversation standing outside BOM. I’m reminded of an action Katie Etheridge did at the National Review of Live Art many years ago, in which she issued non-smokers with fake fags so they wouldn’t miss out on all the best conversations.

For Fierce, like the dearly departed NRLA, is more than a festival. Or perhaps it is a festival in the original sense of the word. A gathering of a community to share a space and celebrate. In this case, a community of artists, writers, musicians and thinkers from Birmingham and beyond – Fierce is both determinedly hyperlocal and ambitiously international (and all things in between). Of course there is a wider audience – particularly as much of the work at Fierce over the years has been presented in public spaces; and collaborations with partners such as Warwick Arts Centre, macBirmingham, and DanceXchange lock into their audience bases – but there is a core group of attendees who are fellow artists, creators, and cultural commentators of all sorts.

So this evening is the official launch of Fierce 2015 – although things actually kicked off the night before at Warwick Arts Centre with the opening of the new Chris Goode show Weaklings, which is a corker of a show inspired by the blog of cult writer and artist Dennis Cooper (reviewed here).

At BOM there are all the usual things you’d expect at a festival launch – glasses of fizz, thank-you speeches, hardcore networking – there’s more to it than that, as many of the installation works presented at this year’s Fierce are sited here – so people like me who hate networking and always spend time at launches talking to people they already know can actually see the work being talked about.

The basement space has been taken over by Birmingham-based One Five West, whose Code and Carpentry is a ‘series of interactive objects’ encouraging ‘tactile creativity and play in a digital age’. The space has the feel of a fairground sideshow or an old-fashioned games arcade, repossessed and radically altered. Low tech is the name of the game – reclaimed and customised furniture meets schoolboy (or in this case, girl) electronics kit. There are glass-topped boxes on legs (think pinball table) that change colour when you approach them, hall-of-mirrors screens with in-built theremins, and love-seats lit with miniature LED lights that are touch sensitive. When I first enter I’m alone, and enjoy the awareness that I am shaping what I’m seeing and hearing. As the space fills up, there’s a different enjoyment, feeling part of a big moving mechanism of people and machines; everywhere a mash-up of sounds, lights, and shadows with it hard to tell who is instigating what.

Meanwhile upstairs, there’s a screening of Orange Bikini, a film by Emily Mulenga, who uses video and digital art ‘to explore ideas around the (female, Black) body in the Internet age’ . Like One Five West, Emily Mulenga was a Fierce FWD 14 artist – Fierce FWD being a scheme that supports emerging artists from or based in the West Midlands (in Emily’s case, Burton-on-Trent).

In Orange Bikini, Emily’s avatar is seen moving through a series of brightly coloured and fast moving landscapes. It’s somewhere between a girly Disney movie, a Japanese anime, and a quest-based video game – a kaleidoscope of fast-moving mutating landscapes in which our heroine poses, twerks, pole-dances, drives and swims. Here she is shaking her butt in skimpy white shorts and afro hair, a Blaxploitation movie star with a tiny waist and big curves. Now she’s whizzing along a multi-coloured cityscape in her Cobra sports car, long sleek hair streaming in the wind. Then she’s sitting on a tropical beach at sunset, the screen a rainbow of hot orange tones, which shape-shifts into a field of daisies, our heroine sporting My Little Pony pink hair. Next she’s swimming with dolphins, her floating turquoise hair longer than her body. This is a world of unfettered freedom and happiness, in which the self can be anything the artist wants it to be – a body moulded by the mind to absorb, reflect and contradict the oppression of cultural expectations heaped upon young women of colour. Orange Bikini is very lovely piece of work, stating its case for self-determination with humour and joy.

Emily’s work can also be seen in the magazine Contemporary Other, which is launched at the Fierce opening. The editor is Demi Nandhra, who is another of the Fierce FWD 14 artists. Contemporary Other is an actual print magazine – hurrah! – 36 A4 pages of quality heavyweight paper with perfect binding. Before I get to any reflection on content, can I say how much this pleases me. What we find inside is creative and critical writing, hand-drawn illustrations and digital artworks. The theme of this launch issue is ‘feminisms’, and the edition includes poetry, poetic prose, manifestos, presentations, essays, and statements – I am Not a Feminist by Zoe Samudzi, and An Open Letter to a Trans-Exclusionary Radical Feminist, to pick two examples, are provocative and polemical, addressing current issues in contemporary feminism of white supremacy and the acceptance (or otherwise) of transwomen within feminist communities. I’m personally more drawn to the visual arts work, which manages to be strongly political without the polemic. Joiri Minaya’s DWGS postcard series gives us a beautiful collection of portraits that reclaims and updates the sort of imagery used by painters of the ‘exotic’ female form, such as Gauguin. Kamal Badhey’s I Must Remind Myself is a series of photos in which faces or objects are overlaid with texts: a chest-of-drawers with clothes tumbling out bears the words ‘imprints of cruel memories’. Emily Mulenga’s contribution is a photoshopped and digitally enhanced self-portrait – skin made paler, hair changed from black to blonde, waist impossibly slim, breasts ridiculously large, pubic hair airbrushed out. Written on the image are the words ‘the tan lines will fade but the memories will last forever.’

Key to Emily Mulenga’s work is the notion of a safe space – an idea with a great deal of currency in the debate on ‘contemporary otherness’. It is therefore unsurprising, when entering the room for Selina Thompson’s Race Card installation, to see the phrase ‘safe space’ cropping up numerous times on the 1000 questions she has written and posted all around the walls. Here’s the idea: you enter the room, alone. You read the cards in numerical order, and you stop when you reach one you want to answer. You’re advised to try to pick one that isn’t too easy for you. You write a response and pin it on the wall, so others who enter the room can see your answer. You then pick another question that you can’t answer, and copy that one out on a new card which you take home with you to reflect on.

Here are some of the questions, all of which relate to enquiries around race and cultural identity:

How do you go about exposing white supremacy in liberal arts spaces?

Do you feel comfortable using terms like ‘black’ and ‘white’ to describe race?

What does it mean to be black?

What does it mean to be white?

Whatever happened to multiculturalism?

How can I be more like Grace Jones?

Who is Live Aid for?

What will freedom look like?

When I enter the room, there’s an immediate practical problem in that the early-number questions are up high, written in small and difficult to read script, white on black, set in a dim space – there’s no way I can read them. So I immediately disobey the rules and start reading things in a random order. Inevitably, I spot things that push buttons for me: ‘Who is more problematic, famous racist Nigel Farage, or the liberal journalist politely asking questions?’ promotes a bout of inner rage as I rail against the idea that we can’t ask questions of, or listen to responses from, people we don’t agree with. I decide not to answer that one. I also note ‘Why do we have borders?’, ‘Is immigration traumatic?’ and ‘What will it take to stop Katie Hopkins?’ as they relate so strongly to current work I’m doing with people who have migrated to the UK. Aware that although I’ve been told to take as long as I like, there’s a queue outside, I stop dithering and pick ‘What labels does your body wear?’

Race Cards is a thoughtful and thought-provoking piece of work, but there are flaws in the execution: those up-high cards you can’t read; the fact that you are told to write your reply in red ink, but there is only a black biro available which is confusing; the ‘take as much time as you like’ directive which just makes you feel stressed when there are a load of people waiting outside – I’d prefer a fixed time limit. But these are things that can be easily readjusted. The main thing is the core intention and content of the piece, which is sound and good.

The labels my body wears – and whether I accept or reject them – ends up tying in neatly with my experience the next day (also at BOM) of Spit Kit by Bristol-based artist Ria Jade Hartley. In this, you are led into a room upstairs that has been converted into an art-sci laboratory. Vials containing tiny samples of saliva are lined up on shelves, a glass-fronted cabinet contains a selection of scientific and medical instruments, and a number of lines are pegged with photos of human faces and bodies adorned in exotic decorations (white clay, feathers, painted lips…). There is also a wall of pictures of the artist enacting earlier works from the Genetic Body series, of which Spit Kit is the latest strand.

I’m greeted by Ria, invited to sit down, and then presented with the sort of official document we are all familiar with, in which questions of nationality, cultural identity, and race are ascertained. I go for my usual replies: Anglo-Irish. Mixed other. Prefer not to say. We talk about these answers. A sample of saliva is taken, prompting a discussion on DNA testing and ancestry. I’m told my saliva won’t be tested, just added to the museum of samples. I’m asked if I can go back six generations. I can only manage three – parents, grandparents, great-grandparents. This already takes us back to the mid 19th century. Irish. English. Eastern European Jewish. The conversation takes us to a discussion of intermingling cockney London communities, Portuguese sailors arriving in the Irish port of Cork, and the Norman invasion of Hastings. The final stage of the piece leads to me embracing the term I’m happiest with to describe my race, ethnicity, and cultural heritage. I decide on ‘human’ – which is, as well, the only label I was 100% happy for my body to wear in Race Cards. Ria Jade Hartley’s Spit Kit is a great experience – a well-structured, warmly embracing, and thought-provoking work.

Meanwhile, on the streets of Birmingham, Permutations in the City continues its investigation of movement in public spaces, partly choreographed and partly improvised around a structure, and inspired by Stefan Jovanovic’s provocation: How can bodies be used to alter the social scripts inherent in public space? Friday is day two for choreographers Neil Callaghan and Simone Kenyon and their team of guest dancers. On Thursday, I watched two of them work their way around the grimy urban environment of a motorway underpass. Although the movement work was fine – simple, slow encounters between two bodies negotiating their way along the inside edge of the boundary wall – I felt a little bored. Partly, I think, because I have seen so many choreographic works in cities that seemed to have an identical intention. (Although I realise that I am very old, and have seen a lot, and that young artists need to feel that they can discover things for themselves.)

I have quite a different reaction on Friday, when I see another pair of dancers in the busy Victoria Square in the city centre. Here, the piece is less about a response to urban architecture, and more about the social space. In the underpass, the dancers negotiating the concrete walls and floor were watched by a few Fierce aficionados, with an occasional passer-by scurrying past uninterested. It seemed a pretty insular affair focused on the bodies’ relationship to the physical environment. In the square, there are people who are here to enjoy the autumn sunshine, to take a cigarette break, leaving their offices for a take-away coffee, or sitting on a bench with a lover. People who become slowly or suddenly aware of the two figures standing still and leaning against each other. There is a strength in the fact that the dancer’s bodies are locked in to each other, with movements mostly a slow and cautious embrace and unwinding. A pair of builders walk by looking a little bemused, glancing back over their shoulders; a group of charity workers stop their drill when they realise they have competition; a man asleep on a bench with a copy of the Sun over his face sits up to ask me if I know ‘what that’s all about’. As is oft the way with work in public spaces, I enjoy watching the incidental audience as much as I enjoy watching the performers. ‘But what’s the point?’ says the Sun reader. Just being there, doing it, is the point, I feel.

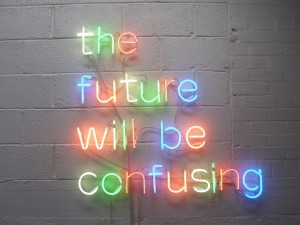

The performers unlock their hold and walk off, moving off to their next site. Sadly, my time is up and I have to go too, to head for the train station. I leave Birmingham regretfully, knowing that I will be missing a fabulous weekend of work that will include terrific new shows by Ursula Martinez, Fernando Belfiore, and Kate MacIntosh. I’ll miss the Saturday night Club Fierce featuring not only Gazelle Twin but also Miguel Gutierrez. I won’t get to bring my own record to Montreal company PME–ART’s Bring Your Own Record Listening Party. I won’t get to Sleep with a Curator. I’ve missed my chance to see Tim Etchell’s neon Will Be – in which the words The Future Will Be Confusing will shine out from the historic frontage of the Moseley Road Baths, a foreshadowing of which was seen at Chris Goode’s Weaklings, which ends on those very same words. A zeitgeist thing, or are they in collusion?

This is the last year that Fierce will be curated and directed by Laura McDermott and Harun Morrison. The call is out for a new artistic director – and we can only hope that whoever takes up the post brings as much verve, energy, and ambition to the job as these two, who now move off into their own futures, confusing or otherwise. What will be for Fierce Festival in the future we shall have to wait and see.

Featured photo (top of page): Emily Mulenga Orange Bikini. Photo courtesy of artist.

Fierce is an international festival of cross artform performance centred in Birmingham. The festival embraces theatre, dance, music, installations, activism, digital practices and parties. Fierce fills the city with performances in theatres, galleries and other out-of-the-ordinary spaces. Fierce 2015 took place 7–11 October. www.wearefierce.com

Dorothy Max Prior attended Fierce for Total Theatre 7–8 October 2015.