Dick McCaw is a ball of energy. It would be easy to underestimate the influence he has had over the physical theatre world, both here and abroad, in the five years he has been director of the International Workshop Festival. He is self deprecating and funny, often at his own expense, yet he calmly and quietly brings together some of the greatest teachers and practitioners working in theatre today.

When I went to meet him in his small basement flat in Stamford Hill, I found him waxing lyrical about ‘what makes a good workshop participant' and the subtle delineations of the whole workshop process.

McCaw took over the International Workshop Festival in 1994 from its founder Nigel Jamieson, who he describes as ‘a man who feels concepts like they are concrete, like they are balls you can hold in your hand’. In contrast, McCaw claims he hadn't a clue what he was doing.

‘It is a very special skill. It is very difficult to organise what is essentially a training service. The market does not exist, the service is pretty low key. It happens for twenty people behind a closed door.’

He soon rose to the challenge, however. In his second year as festival director he introduced a theme to each workshop programme. He explains that this was a necessary marketing device, at a time in which the sector the workshop festival had traditionally serviced was undergoing a constant process of change.

‘We were still going for a mime and new circus clientele, but mime had changed its name and new circus had dropped off the path finder, so marketing and programming had to go very closely hand in hand.’

The IWF market is niche, as McCaw explains: ‘If you start wanting to do Colombian snake charming, interesting and beautiful as it might be, who is going to come?’ The festival exists to provide an educational service and, as McCaw points out, ‘what is the point of providing an educational service that no one will come to?’

However, with such a vast array of world theatre practice to choose from, it behoves the director of a workshop festival to sometimes take risks.

‘As with all good programming, it is a mixture of pushing and listening. You have to say “trust me”, and I think there are probably about sixty people who do trust me now, out of four thousand. The numbers are phenomenally small, the margin of error is huge.’

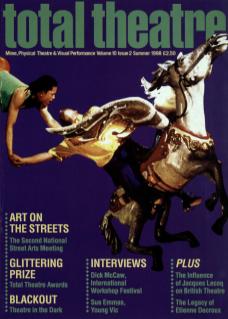

The last workshop festival in the spring, The Way of the Warrior, was a collection of workshops on the martial arts. How does McCaw explain the relevance of martial arts training for the contemporary performer?

‘I inherited the martial arts idea from Nigel Jamieson... People thought [it] would be a sporty, judo-club thing; as Ruth Mackenzie of Scottish Opera said, “it is boys with sticks”. So the whole problem of image, perception and misperception of the martial arts arose.’

But he goes on to explain: ‘I realised that martial arts are nothing to do with violence, they are about control, about discipline. Actually the end product of many of the martial arts are the most beautiful movements. Why? Because they are perfectly in contact with the ground. They understand the relation between two bodies... You are seeing the human body at its peak of achievement. So in terms of training, I could sell it to actors and dancers; in terms of choreography and enhancing performance, I could see how to sell it, and in terms of producing a programme which demonstrated the links between performance and the martial arts, I could see how to sell it to the South Bank Centre.’

The Way of the Warrior was a watershed for the IWF and an achievement of which McCaw is understandably proud. Fifteen thousand people came to see the demonstrations at the South Bank Centre.

Why is it that the workshop festival has always been so oriented towards what we have come to describe as physical theatre?

‘I think that we ignore the expressivity of the body at our peril, because I think it becomes an ever more distant theatre when it's from the neck upwards. If you are only doing text-based theatre, how can you project physically, I mean in terms of stage presence? Or how can you project vocally, in terms of your body apparatus, if you aren't physically aware? One could almost say that there is only physical theatre. We all need a body. It is all a question of degree. I am very interested in exploring theatre which does not rely so much only on a literary text but on a text in the context of other means of expression, simply because I think it is more interesting for the audience.’

David Mamet in his book True or False – Heresy and Common Sense for the Actor, writes off education for actors, considering it a complete waste of time. To quote from Mamet: ‘vocal and physical training can be acquired piecemeal through observation and practise, through personal tutoring, or through a mixture of the above – acting training will not help you. Formal training for the player is not only useless but harmful.’

What does McCaw make of that? He recognises the problems inherent in training provision, as he says, ‘you cannot teach Kallarippayattu in a week’. But he goes on to say:

‘There are some fundamentals of performance which we lose touch with at our peril... I think [the IWF] is an opportunity for professionals, young and old, to re-sensitise themselves... It might be a question of morale, it might be a question of curiosity, it is this almost Brechtian sense of distancing yourself. You cannot distance yourself conceptually because conceptually you can be anywhere, in any time, in any space. You have to give up your whole self which is your body, you have to feel how a Kabuki actor approaches character, you have to feel that their characterisation makes very different demands on your psycho-physical apparatus.’

But for McCaw, it is not a one-way process. It is as much an experience for the teacher as it is for the participant. McCaw has made mistakes, and admits it is a terrible responsibility to choose the teachers, and of course there have been times when teachers have been programmed who are only doing the workshop to show off, to get attention, or even to engage in 'dubious sex seeking activities’.

Before a workshop, McCaw will challenge his teachers quite specifically:

‘There is an awful lot of preparation. For example I invited Patsy Rosenberg, probably Britain's greatest living voice teacher, to do a workshop for dancers. She said, “what do you mean, for dancers?” And I said, “I really believe that it is important for dancers to find their creative voice...” She accepted the invitation and worked with a ballet dancer from the Balachine company, and it was one of the most moving workshops that we have done because she released emotion, introduced people to a new part of themselves.’

McCaw admits that sometimes his requests to teachers do shock them a bit. Over time he has come to realise that, in the workshop setting, the teacher is often as vulnerable as the participants. Silviu Purcarete, proved a particularly difficult nut to crack:

‘He hates workshops, he does not do many but he will do one with me. I mean I can draw things out of people which they might not even recognise in themselves. It is like in relationships, you can often see something in your partner which your partner simply cannot see. We often need the mirror of somebody else.’

McCaw believes the best workshops are when the teacher has learnt as much as the participants. Finding good participants is as important as having a good teacher.

‘It is my job to provide good participants. A workshop is absolutely not about the passivity of the participant... People pay £150 expecting to have £150 worth of educational commodity, which is a very Thatcherite weights and measures approach to education, it becomes a process which is completely transactional. If you bring nothing to the teacher, the teacher has nothing to work with... The dynamic of the workshop is about listening, about re-sensitising, having been desensitised by a business which is very demanding.’

So what qualities does a workshop participant need?

‘As Monika Pagneux used to say about good participants – “you have given me a gift”. People who have that humility, who have that ability not to impose their ego, people who genuinely listen to the teacher and people who can imagine what the teacher is trying to say and secondly try to follow that exercise in an honest, and personally authentic way.’

Although the very essence of IWF is process rather than product led, have there been any tangible results to come out of the workshops? First, McCaw quotes from Lecoq:

‘When someone asked him in a workshop, where is this all going?' He said, “come back in three years and ask that question”. It is like an intra-muscular as opposed to an intravenous injection, it takes a long time to spread through the system and three years later you will suddenly realise, “oh that is what it's about”.’

Working relationships have been formed from the workshops:

‘Henk Chut... always finds actors at IWF workshops, The Right Size came together four years after meeting in a workshop, Bobby Baker took two people from her workshop to be in her show. Hayley Carmichael and Steven Whinnery met each other in a workshop and did a show together. I think it is important to extend invitations to other artists so that they can work in other countries. Jonathan Stone of Ralf Ralf taught in Lithuania as a result of one of the workshops.

Of course MaCaw's visions are often limited by the amount of money at his disposal. He has grand visions:

‘I would have a building with big, well-lit, sprung floor Studios, a big room in which at least sixty people could eat together, and a kitchen where I could cook for them. To eat together is very important, and we could do more smaller projects. For instance, if Anatoli Vasiliev wanted to come over here with twenty Russians, we could have more proper international exchanges. I might be able to do the job better of looking after a particular approach to making performance and a constituency that I am becoming increasingly fond of. We have talked about vulnerability, about generosity, trust, humility, exposure, and these people who I have had the privilege to work with embody all these qualities, and so I like them and so I would like to cook for them!’

And I am sure the feeling is mutual.

The next Workshop Festival, A Common Pulse: A Body of Knowledge, takes place at the London Studio Centre (31 August - 13 September) and Yorkshire Dance Space, Leeds (14-20 September).