“

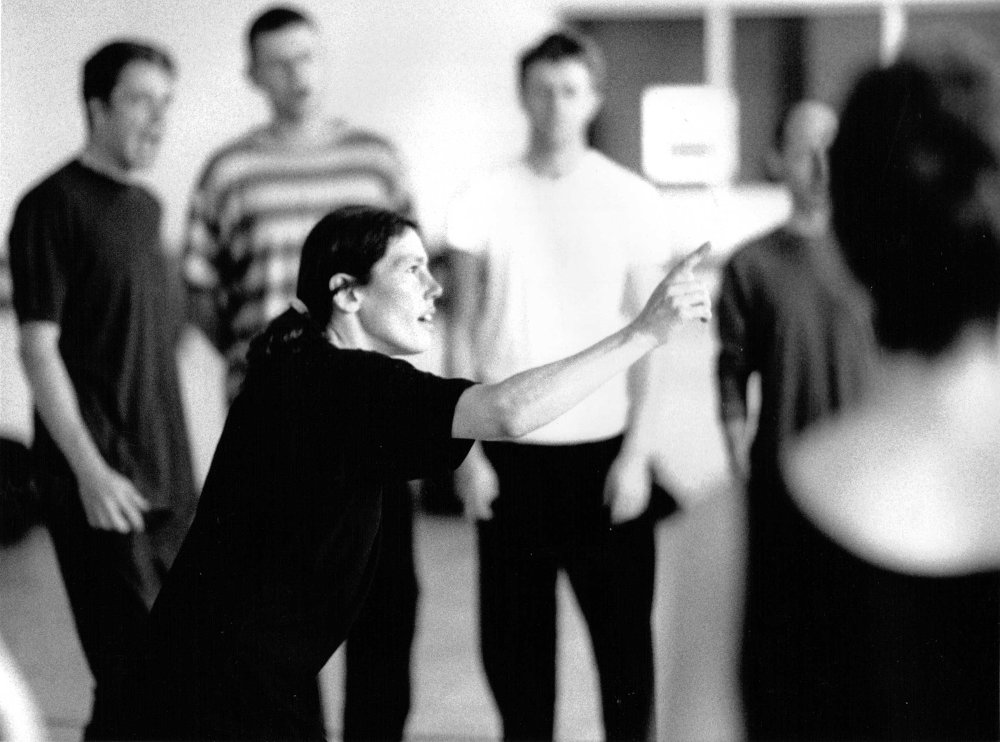

My career in theatre started at University of Cambridge. I was working in a college bar and one of my regular customers told me that he rather admired how I managed to clear a bar when time had been called – a job that took a particular mixture of presence and voice. He said he was starting a theatre company, one that wouldn’t perform in term-time or for students and wouldn’t involve any of the regular Cambridge venues. That man was Carl Heap and the company was the Cambridge Medieval Players. Right from the start, the work of the Players was very, very visual. Carl had been inspired by groups like Peter Schumann’s Bread & Puppet Theater and there was a lot of circus mixed in. Carl had spent time backstage with Billy Smart’s Circus when they came to Cambridge, and as a result every member of the Players had to learn a circus skill: juggling, stilt-walking, tightrope, and so on. I was a musician and played guitar, so that was my bit. Even though the company performed medieval plays, it was popular work and they played everywhere. Performing with them while I was at university had quite a big effect on me. We were using a booth and trestle stage – the precursor of the commedia stage – and with a space that small you have to be very precise in all your movements. It was also an introduction to thinking about how the nature of your work is determined by where you work, who you’re performing for, and who you’re working with. In 1978 I left Cambridge. My guitar teacher, who’d been telling me I was ruining my hands doing gardening jobs, said he’d found me a gig at the Edinburgh Festival Fringe to arrange some music and perform live on stage. When I accepted I had no idea that it could be the start of something – that it might possibly be a job, a calling, a career. It was just a diversion between the end of my studies at Cambridge and the beginning of a PhD at the University of Sussex. The company was ATC, the Actors Touring Company, which had been founded by John Retallack, and his adaptation of Byron’s Don Juan was a huge success and we got a Fringe First Award. But behind the scenes things were chaotic: even before we got to Edinburgh I’d said to John, ‘I need to have some order in my life, would you mind if I take over the management of the company?’ He said, ‘Take over! Nobody likes organising.’ So we became a partnership, and I worked on organising a national tour for the company. You’d hardly know it now, but at that time there was an infrastructure that actively promoted small-scale touring, both at the level of regional boards which organised funded tours, and at the level of councils which had the funds and inclination to support small-scale touring in their villages. At the Arts Council there was a specific department for touring, run by the late Ruth Marks. And you could also rehearse on the dole – another great source of funding. It was an era of political experimental theatre, supported at a cultural, organisational and fiscal level. Eventually things came to a head when I had to make a decision about whether to do my PhD at Sussex or continue with the Actors Touring Company. Finally I decided that I wouldn’t do the PhD, and, moreover, that I was going to leave ATC and propose to Carl Heap that we start the Medieval Players as a professional company. Everybody thought I was completely mad. It was 1980 and, even though there were intimations that the party was starting to cool down, there was still quite a lot of funding available and ATC was on the ascendency. But the reason I did it was that, although middle class, I’d grown up pretty rough around the edges, and honestly I wouldn’t have gone to ATC shows. They were excellent. They were fantastic. But I wouldn’t have appreciated the literary subtlety of the work. The Medieval Players on the other hand were very much making work for a popular audience. Later in the 1980s I ended up starting my own management company, which I ran until 1992. Alongside the Medieval Players we worked with a folk group called The Carnival Band which had been started by Andy Watts and Giles Lewin (with Maddy Prior a frequent collaborator), and then later on with Nigel Jamieson’s company Odyssey on the shows Blood Wedding and Macbeth. I’d met Nigel through my sister, Ali McCaw. She’d started a theatre company called Trickster with Rachel Ashton, and after they’d been going about a year I remember seeing a show where they’d got this tall, very charismatic man performing with them. That’s how I got to know Nigel, and heard about it when, in 1988, he started something called the International Workshop Festival – a project that I would join just a year later. Part of Nigel’s inspiration for the International Workshop Festival had been Die Werkstadt in Berlin, organised by Nele Hertling. Both of us shared the same idea that a festival packs a large amount of activity into a limited space and time: it’s an intense gathering where people meet and exchange ideas. And right from the start the IWF was a long day, with warm-ups before the workshops, wind-downs after, and then talks in the evening. That made for more or less a twelve-hour day, 9am to 9pm. We worked around the country – in Derry a lot, in Edinburgh, in Glasgow, in Warwick, in Bristol, in Nottingham, and of course in London. During those early years we worked with artists like Clive Barker, Monika Pagneux, Bread & Puppet Theater, Jos Houben, Barney Simon, and Augusto Boal. In 1990, Bread & Puppet Theater gave a workshop in a disused shirt factory in Derry as part of a larger IWF programme called Finding a Voice. Afterwards, Peter Schumann wrote a letter celebrating the ‘confusion’ of the theme, scope and complexity of the project: 'In principle I confess to this confusion as the logical starting point for any artistic enterprise. The enormously unimportant sitting together of forty-five human strengths and weaknesses, who are trying to find out why and how they are sitting there: where are we? at what moment and how do we transform this untamed awareness into the famous intensity which is called creativity? The classical definition of creativity as the labor which produces and, at the same time, solves the problem, applies to this moment.' Between 1989 and 1991 I worked as IWF’s associate director, but what nobody knew was that Nigel actually spent half his time in Australia because he’d met someone in Australia whom he later married. In 1992 he left for good and I took on full responsibility for running the IWF. In 1993 we worked out of England with collaborations in France, Italy and Spain, and so the first proper festival that I did was in 1994. Nigel’s being away in Australia was still a kind of secret, and so I made a festival that looked exactly like one of his earlier ones. And it was a success. But afterwards our administrator Jenny Klein handed me her report on the festival, which basically said that we were marketing to an audience that didn’t exist anymore – and she was right. The festival had been built for a specific purpose and audience – at the time, the mime and new circus movement – but in ’94 that was changing. Over those six intervening years mime had become a dirty word; things had shifted to physical theatre or visual theatre. The funding environment was also changing. Artists had to consider themselves ever more as businesses, and so I felt that as the artistic director of the IWF I had to get into a real and meaningful dialogue with artists in order to answer their actual needs. In that sense, Jenny helped me to reinvision both the festival and what my job was in programming it. Whereas Nigel had had the romantic phase of cutting and burning the ground, creating a space in which to build his thing, I was left with the thing, and the task of finding out what it could do. I came to realise my job was much less god-like and much more broker-like. My role was to get the right people to come to a workshop where they would be investing a lot of their time, if not a huge amount of money. And the programming itself became more and more collegiate as time went on: part of the college was my colleagues in the office, the other being the regular teachers like Mladen Materic, Dominique Dupuy, and Claire Heggen. A big turning point for the IWF came in 1997. All our equipment in the office and all the recording kit that Peter Hulton was using to do our festival documentation was falling apart. At the same time the digital age was coming in, and we needed to make the move from analogue to digital. I started to make a large application for lottery funding and one of the requirements was that I had to submit a five-year plan. In 1995 we’d themed the festival around the relationship between the martial and performing arts, and in ’96 the key concept was movement, so starting from that foundation I developed A Body of Knowledge, a programme that would explore, from one festival to the next, themes that are very basic to the performing arts: voice, rhythm, character, dialogue, and space. We got the grant, but more than that the Body of Knowledge programme gave a focus to each festival. 'One time in Derry, Helen Chadwick, the extraordinary singing teacher, had an exchange at breakfast with Andrew Dawson. Later that day the participants of Andrew’s class were all lying on their backs doing gentle Feldenkrais stuff when suddenly, as if from heaven, all these people filed in and started singing a Bulgarian lament... The festivals were exchanges between teachers and participants, but they were also exchanges between artists. There were real meetings of minds.' Every year I would commit myself to doing one week’s worth of workshops, the same as the artists. No flitting around. Looking back now, it’s hard to pick favourites. And when I think about the workshops that stuck with me, it’s not because one teacher was better or worse than anybody else – it’s because we struck up a dialogue. Because they had something that resonated with me. So I think of Mladen Materic, because he addressed a certain sensitivity to those elemental aspects of theatre: substance, shape, light, form. Or Claire Heggen because of her movement. I think of the sense of play that Clive Barker had, or of Phelim McDermott’s grasp of the materiality of theatre, the timing, what you look for in movement. There were many who left indelible marks. I always programmed Feldenkrais wind-downs with Scott Clark, and every festival would have a workshop with Garet Newell, who became my trainer when, after finishing the Body of Knowledge programme and leaving the IWF, I later qualified to be a Feldenkrais practitioner myself. And that’s an education that still continues today: I’m still being taught by Feldenkrais and my teaching of Feldenkrais. Then there was Geraldine Stephenson, who gave me more than 200 three-hour private lessons in the Laban way of moving and trained me as her assistant. One of the most remarkable teachers I worked with was Monika Pagneux. The first thing that struck me was how frightened she was at the start of the workshop. I later understood why. After the workshop had finished we were going through the participants to decide on who would be selected to go forward for a more advanced course. Her fingers ran down the names: ‘Non, non, non, non…’ And then suddenly: ‘Oui. Oui – lui, c’est un don.’ He’s a gift. What did this mean? Monika explained that many of her exercises are empty structures. Their success depends on what the participants do with them, what they find in them. The person who was a ‘gift’, had brought something completely new to the exercise. The significance of this definition of an exercise has only recently struck me. In a workshop or any teaching situation you never know how participants are going to respond to what you offer. That’s why Monika was frightened: teaching is a real risk. What happens if everything fails and nobody responds to these basic structures? If nobody finds them a stimulus – a provocation? But then when the participant does respond – really responds – and filters the lesson through their own style, and comes up with something which in every way answers the simple instruction they were given and yet presents the teacher with something they could never have foreseen – that’s when a participant is a gift. Although it’s now been more than fifteen years, directing IWF was a job that still fuels me today."The International Workshop Festival

Dick McCaw is a senior lecturer in theatre at Royal Holloway, University of London. His forthcoming book Rethinking the Actor’s Body – Dialogues with Neuroscience will be published by Methuen in 2020. He is also a qualified Feldenkrais practitioner.

The International Workshop Festival archive is housed at the British Library as part of their Sound and Moving Image Catalogue. It contains video and audio recordings of talks and workshops, alongside photographs, programmes, reports and other materials. The archive of the Medieval Players is housed at University of Bristol.

John Ellingsworth interviewed Dick McCaw March 2019 at the British Library.