Performer Alice-Therese Gottschalk sits on the edge of the stage with a finely decorated box on her lap. She closes her eyes and slowly, almost ceremonially, opens it towards us. Fellow performers Raphael Mürle and Frank Soehnle hover in the shadows just behind her, holding whatever is inside by fine wires. With precise and delicate manipulation, they coax a pair of golden hands up out of the box, each articulated joint responding to their tiniest tweak. Slightly larger and bonier than a human’s, the golden hands explore the woman’s own hands tenderly, playfully. They trail their fingers over her face and through her hair, and she allows them, submitting to their will. It’s sensual rather than erotic, uncanny rather than creepy. Gradually the hands are drawn up higher and attached to wires either side of the stage, where they remain suspended throughout the performance like apostrophes, as if holding the show between them.

Performer Alice-Therese Gottschalk sits on the edge of the stage with a finely decorated box on her lap. She closes her eyes and slowly, almost ceremonially, opens it towards us. Fellow performers Raphael Mürle and Frank Soehnle hover in the shadows just behind her, holding whatever is inside by fine wires. With precise and delicate manipulation, they coax a pair of golden hands up out of the box, each articulated joint responding to their tiniest tweak. Slightly larger and bonier than a human’s, the golden hands explore the woman’s own hands tenderly, playfully. They trail their fingers over her face and through her hair, and she allows them, submitting to their will. It’s sensual rather than erotic, uncanny rather than creepy. Gradually the hands are drawn up higher and attached to wires either side of the stage, where they remain suspended throughout the performance like apostrophes, as if holding the show between them.

It’s a powerfully beautiful and moving opening sequence, which, by juxtaposing the hands of the marionettists, the marionette-hands, and those of the person experiencing the marionette, invites us to place ourselves in the hands of the marionettes, to allow them to take us into their worlds, and to do so with respect and indulgence.

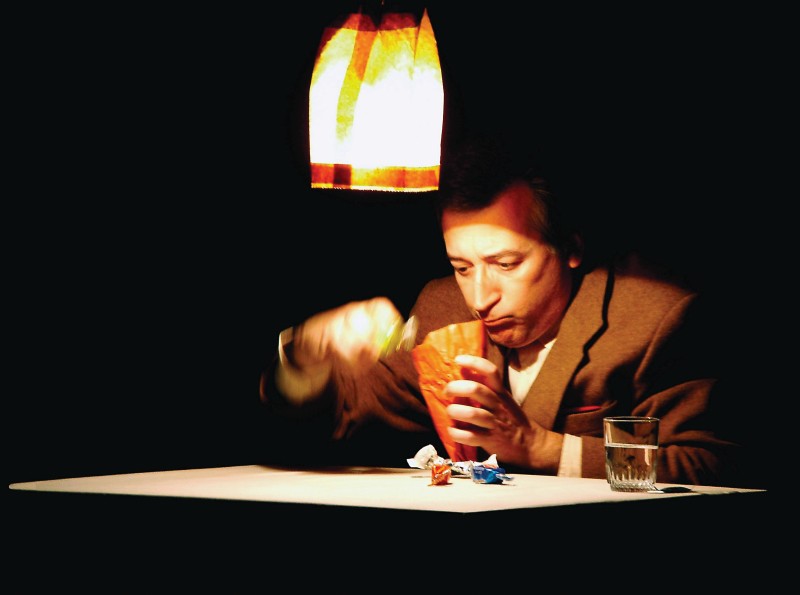

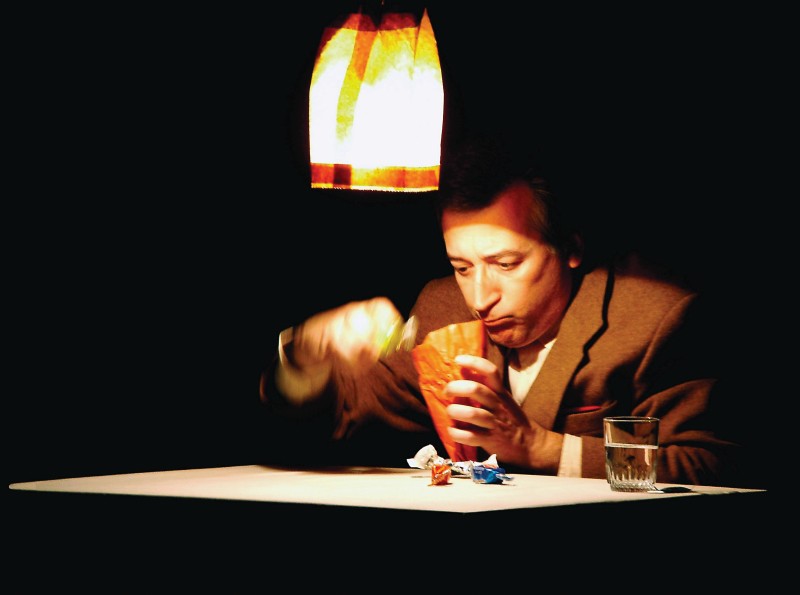

Wunderkammer offers a privileged view of a precious menagerie. These are intriguing, strange creatures and one by one they’re brought before us to discover themselves and their surroundings as if for the first time. A tiny paper creature longs to fly and finally succeeds in taking to the air with the help of a kite; a comic eye-rolling, scissor-wielding beast looks furtively about, snipping away at anything that comes close; a pair of musicians, their bodies their instruments, accompany a deliciously loose-hipped belly dancer.

Gottschalk, Mürle, and Soehnle are virtuosic performers. As caretaker-proprietors of their collection, they confer immense dignity on every marionette, paying careful attention to how each one arrives before us and departs from view in pieces that are like finely crafted miniatures. In their beautifully judged interactions with their charges they at once allow the marionettes’ characters to reveal themselves and are surprised and entertained by how they behave.

There’s something timeless about the collection, its inhabitants’ unique conditions nevertheless seeming to represent something of common conditions across the ages. Some of these creatures seem to have been discovered in an old world, others brought to us from the future. The marionettists’ dark serge costumes suggest travelling players, roaming in bitter winters through central Europe and rigging their rusty curtain in the dim fire-light of oak-panelled hostelries, while the music – a sometimes jazzy, sometimes sparse synthesis of electronic sound, harpsichord and cello – takes us elsewhere, even somewhere otherworldly.

The whole is enchanting. Indeed, the puppetry here is so fine it at times feels like a kind of magic, miraculous even, as when a foot-high acrobat swings effortlessly between the limbs of all three performers with staggering ease and grace. It’s exquisite stuff and we’re under its spell throughout.