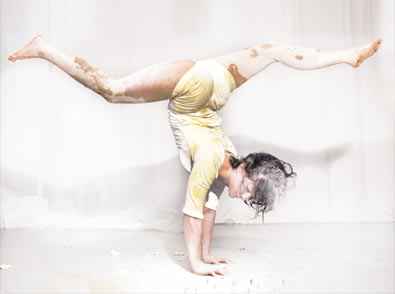

Five performers, two female, three male, walk through the audience, down the aisles, making their way onto the small, round stage in the centre of the Spiegeltent. They are dressed in a tasteful palette of maroon, stone, and dove-grey. A red pendant lamp hangs over the performance space and the five group around it – a beautiful oil painting. An ensemble acrobatics number explodes out of the huddle, in which the five bodies twist and tumble and form astonishing Chinese Puzzle shapes. Men and women base and fly. Three-person-high towers grow and fall as bodies scramble up and down other bodies. Pyramids are built with a body in backward-bridge position astonishingly holding the weight of others clambering on top of her. They organically morph from one shape and formation and cluster to another. What skill, what beauty. And my goodness these three-high shoulder stands look so extraordinarily high and frightening when you are just yards away from the performers – the pleasure of seeing circus work in the round, with everyone close to the action.

This opening section sets the bar for an hour of immense and awe-inspiring circus skills, elegantly packaged into a nicely designed show that sets out to investigate joy and intimacy. There is no narrative beyond the stories intrinsic to the scenes themselves, which have a very lovely gender-loose mobility, suggestion encounters between friends and encounters between lovers (of all sexes). The performers are the three (male) Casus co-founders Natano Faanano, Jesse Scott, and Lachlan Mcaulay, with two new female members of the ensemble, Abbey Church and Kali Retallack, joining them for the creation and presentation of Driftwood.

Skills-wise, the emphasis is on acrobatics/acrobalance. Equipment is used sparingly, although we do, along the way, get aerial hoop, hula hoop, trapeze, and rope. All, it goes without saying, are used with great skill and flair. The trapeze act sees an elegant alternating of singles and doubles work; in the hula-hoop act, two women and one man (and nice to see a man hooping!) act out a kind of joyful playground game. There is a gorgeous acrobalance routine between two of the men which plays on capture and release, with one placing his eyes over the other’s eyes as they cartwheel and tumble together. The women capture our attention with their ability to base and fly with equal assurance. Natano Faanano gives us outstanding strength and beauty when working in partnership with Abbey Church, in a choreography that seems to swing between acrobatics, martial arts, and ritual dance. He also allows himself the indulgence of a little bit of burlesque-ish mime, reminding us that he is also a co-founder and star of the boylesque Briefs company. He’s older than the others, and brings a gravitas to his work that I’ve always admired. The structure of the piece works, for the most part, although I find the placing of ’s corde lisse act a few minutes before the very end a little odd as it seems to interrupt the concluding rhythm of the show.

Scenography relies mostly on the bodies in space and the lighting: that pendant lamp is used in little interludes of whimsical physical comedy, between the major scenes.The lighting design is excellent – moving from low and moody, the red shade of the pendant the focus, to a whirligig of lights flashing a rainbow of colours off of the stained glass windows of the tent. The company work to an eclectic selection of music tracks that includes jazzy rhythm and blues, moody contemporary ballads, and whimsical waltzes.

Casus are the company that made the highly successful show Knee Deep – although their enterprising and inventive co-founder member Emma Serjeant has parted company with them, and is presenting her own show, Grace, at the Edinburgh Fringe 2016. Another sometime performer in Knee Deep is also in Edinburgh for August, with Perhaps Hope at Circus Hub. Both of these productions are shows that aim to smudge the boundaries between circus and theatre; to push circus into something other than well-executed skills.

Driftwood is a clever creation that is elegantly designed, and beautifully performed. It is a highly tasteful and well-executed piece of new circus – but it pushes no boundaries. It is, however, great circus – and that is no doubt more than enough for the sold-out crowd of 400 punters at the Palace du Variete Spiegeltent, who were suitably wowed and stunned, and showed their appreciation with rapturous applause.