Dorothy Max Prior is seduced by Brazilian company Cambar Coletivo’s playful invasion of public spaces

It is mid-afternoon on a hot summer’s day, and a group of people are taking a walk along the dusty streets of Barao Geraldo, a small town near Campinas in Brazil. Nothing unusual there, perhaps – but the group have an odd and interesting energy, attracting the attention of passers-by and car drivers. They move as one organic body, taking silent collective decisions on when to speed up or slow down; when to cross roads; when to pause to stare at a torn poster on a wall or at the tinsel wigs in a Carnival shop window. As the pack veers off the pavement and onto a roadside grassy area, leaves crunch underfoot. As we surprise ourselves by walking through the open door of a bar, the old men sitting on the inevitable yellow plastic chairs turn away from the football match on the screen to stare at us, the interlopers.

So, this is day three of Labirinto Urbano – estratégias para se perder’ (Urban Labyrinth – strategies for getting lost), the halfway point of a week-long programme created and led by Cambar Coletivo. Sitting somewhere between a workshop and a collective creation process, the week is a full-on immersion in contemporary performance practice. It is held as part of Lume Theatre’s annual season of workshops, and as with all of the courses in this much-admired summer school, participants are a solid mix of experienced practitioners, younger artists, and students.

Walking – performative walking that is, in one form or another – is a key element of the collective’s work. The workshop times vary daily, and in one evening session, we are sent out onto the night-time streets armed with maps of our own creation. This map-making is a two-day process that starts with mapping our bodies, our feelings, our responses onto paper with coloured chalks and pens; then moves into finding ways to enter and navigate our maps; and eventually to alchemically reducing the map to its graphic essence.

Following my green-ink graphic – an anti-clockwise spiral, a sharp narrow point, and two big curved hills – leads me from the relatively safe and civilised streets dotted with samba bars and pizza parlours that are close to Lume’s base, into the less secure territories of the badly-lit track skirting the local wild park – a path I walk regularly in daylight but have never ventured down alone after dark. Strange noises from the forest and an odd smell of rotting meat almost send me scuttling back the way I came, but I persevere. As we take this particular walk, we are under instructions to make a continuous sound recording of our responses. It is arguable whether talking to myself into an iPhone actually makes me safer on the streets of Brazil, but there is something reassuring about the sound of my own voice. At one point I sing…

On another occasion, we are again out on the streets – this time paired up. One person is masked and the other leads them around, inviting them to touch, feel, and listen to what they are led to encounter. It’s a familiar theatre exercise for those of us who make site-responsive work – but this has an added twist. The eye-masks we wear feature an image of open eyes, giving the wearer a strange other-worldly appearance. As the exercise takes place in public space, the impression is of a team of man-machines manipulated around, or placed in the space like sculptures, an image to be enjoyed by anyone passing by.

The open-eyed eye-mask is an image I’ve encountered before – a familiar motif of the work of Flávio Rabelo, one of the four founder-members of Cambar Coletivo. I first met Flávio (and the other three members of the collective) when I took part in Zecura Ura’s DRIFT 2011, held in upstate Rio de Janeiro. All four were then members of Zecora Ura, creators of the highly acclaimed Hotel Medea project, which in its final incarnation became a midnight-to-dawn interactive performance that wowed audiences at London’s Southbank Centre, and won a whole raft of awards and accolades at the Edinburgh Festival Fringe. The Hotel Medea project, as well as being a major part of Flávio’s artistic work from 2006 to 2012, became the subject of his PhD at University of Campinas, studying under the tuition of Lume actor and researcher Renato Ferracini. Flávio and I also crossed paths in the BR-116 project, a season of Anglo-Brazilian performances in public spaces, created in collaboration with LIFT and held in London in September 2012, at which Flávio presented a piece called Take ]me[ a-way in which, masked and dressed in a long gown, he places himself in a vulnerable position, sitting or standing on a street corner, inviting passers-by to take him for a walk to anywhere in the vicinity, describing the walk to him if they wish.

Raquel Aguilera, whose background is in dance and movement theatre, was drawn into the world of Hotel Medea through a workshop in Rio led by the project’s directors, Jorge Lopes Ramos and Persis-Jade Maravala. Raquel saw the call and was interested in the opportunity to work with Persis Jade Maravala’s Grotowski-based processes, and also to work with Butoh and Capoeira Angola. Her curiosity was piqued – particularly about the inclusion of Capoeira Angola, an Afro-Brazilian cultural manifestation that was already a part of her ongoing work in popular and interactive forms of dance and performance. ‘I lived most of my life researching and learning dancing, singing and drumming’ she says, and goes on to talk of the celebratory-political performance world of popular demonstrations in Rio de Janeiro and Maranhão: ‘We occupied the squares and streets, holding street parties, and Capoeira Angola gatherings’ She talks of the desire to ‘legitimise public spaces as recreational spaces through rituals, play and joking’ – and in this I am reminded of the work of that late great Brazilian theatre-maker Augusto Boal. So with all this in her blood and in her heart, she took the plunge into what would become Hotel Medea, performing in all the incarnations of the show from then until its last manifestation in London and Brasilia in 2012. She talks of Hotel Medea as: ‘A daring and subversive project, which affected and radically transformed not only my way of being in a creative process, but also the mindset of life as a whole.’ She sees her time with Zecora Ura as providing the basis on which she and her Cambar Coletivo colleagues would build their future model of artistic coexistence.

For James Turpin, the only English member of Cambar Coletivo, the

path to Hotel Medea was a rather different one. Having initially met Zecora Ura’s director Jorge Lopes Ramos at Rose Bruford drama school, James lost contact when he moved to Paris to study at the Ecole Jacques Lecoq, but stumbled across an early-stage showing of scenes that would become part of Hotel Medea when these were presented at the late lamented Shunt Vaults at London Bridge. A year later, Zecora Ura were developing the second and third parts of the Medea trilogy in a residency at Shunt – with James in place as Medea’s errant husband, Jason. After five years of travelling to and fro between Europe to Brazil, James made the decision to move his family home to Brazil, and become one of the co-directors of the Brazilian Zecora Ura company.

Roberto Rezende (sometimes known as Carlos) is an artist with many strings to his bow. Having graduated in law from the University UNIRiO he went on to train at Brazil’s EAD/ECA/USP School of Dramatic Art. He has since worked with many different companies and projects. I know him through his work with Zecora Ura, but also as an actor with the renowned Sao Paulo company Teatro Vertigem, whose site-responsive show Bom Retiro was a beautifully-realised exploration of the old rag-trade neighbourhood of Sao Paulo. His contact with Zecora Ura began informally at a workshop held at Lume Theatre in 2007. He was subsequently selected to join a new ‘intensive meeting at dawn’ in the town of Miguel Pereira, in the state of Rio de Janeiro. He describes this experience as ‘an intense week of work and revelations’ – particularly the day spent in the woods of Vera Cruz (a kind of secluded ranch or farm) playing, without interruption, from midnight to six in the morning: ‘It was one of the most powerful encounters I’ve had as an artist,’ he says.

All four were thus at the heart of the development and realisation of Hotel Medea – as creators, performers, and co-directors of the producing company. But by 2012, changes in the dynamic of the Medea collective brought an end to the collaboration, and the UK-based wing of the company (led by Jorge Lopes Ramos and Persis-Jade Maravala) and the Brazil-based group parted company. Roberto, Raquel, James and Flávio decided to stay working together, developing working practices that had evolved through their time together on Hotel Medea, and instigating new ones. Flávio cites some of the examples of working practices from Medea that they were all keen to develop including: ‘Active participation with the audience in the structure of the actions; the multidisciplinary nature of our creations; and an interest in one-to-one works’. New ideas included the development of the Urban Labyrinth, which the group see as ‘our main project, our research lab’.

And so – what to call themselves? Cambar Coletivo has a lovely resonance and alliteration in Portuguese, but is difficult to translate into English. At least, ‘coletivo’ is easy enough: a collective. A collective that isn’t restricting itself to being a ‘theatre company’ but which is open to using whatever aspects of art, performance, theatre, dance, film or anything else that it chooses at any given moment. ‘Cambar’ is more difficult: one translation is ‘to jibe or to tilt’. There is a sense of something that is off-kilter, or jarring or re-aligning in some way. A sort of ‘playful instability’. The group wanted a name that wasn’t too easy to pin down; and also a name that included a verb; intimating a dynamic call to action.

In the past couple of years, Cambar Coletivo have instigated fifteen manifestations of the Urban Labyrinth: a workshop process that marries training and creation; a collective engagement with other artists in an investigation of the environment through games, mapping, walking, and other strategies for getting lost, and thus re-finding, the streets and public spaces of any given city or town.

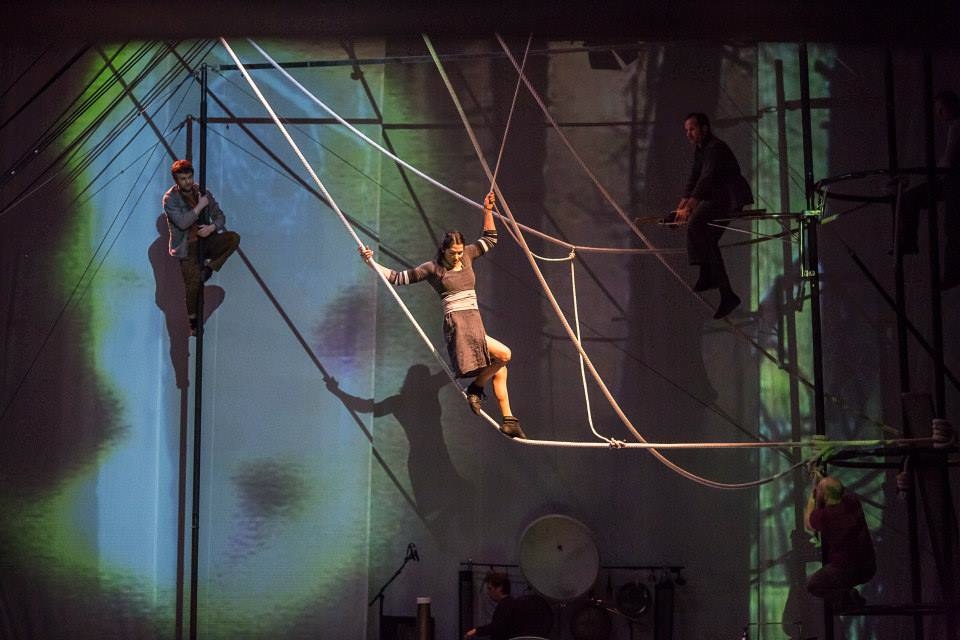

Cambar have concurrently developed a number of other projects. They are, for example, starting work on their first collective performance work, called 3×1 Rhapsody in Red. In addition, they are developing other projects in cities around Brazil. In Diamantina, where Flávio lives, he has recently started Capistrana Líquida – vias de pertencimento (Capistrana liquid – ways of belonging) creating walking routes through the historic city centre of the town; each route having a theatrical element created in response to the route itself and to the architecture and characters linked to it. As Flávio says: ‘In a very clear way, this project is the result of research done with the Urban Labyrinth, and the goal now is to understand how our methodology can launch other creative processes’.

James mentions another aspect of the collective’s work: their involvement in the Festival de Apartamento, an important ongoing and itinerant performance festival in Brazil that occurs not within the confines of theatre spaces and galleries, but in private houses and apartments. (I’m reminded of the long-standing Home Live Art project in the UK – although this has moved into rather different public territories in recent years, so it is good to know that the model is proving successful elsewhere in the world). He also flags up another whole dimension: a step away from what we might call the performance art ghetto into the real-life favelas of Rio de Janeiro and Niteroi, running theatre and performance workshops for children and young adults, and very shortly working in the same way with a group of senior citizens. ‘Our interests are broader than just actor/performer training and professional artistic realms,’ says James, ‘Our work permeates into the day-to-day lives of people, organisations and spaces outside of the established artistic realm.’

Raquel comments on the widespread nature of the Cambar Coletivo’s work, in both the geographical and artistic sense, and on how the individual and the collective interact: ‘Our head office is virtual, and the occasional live meetings are always permeated by the freshness of longing and desire. What renews us and opens a space and time for each of us is the fact that although a collective, each of us has preserved his or her own individuality.’ Each group member’s own solo performance works and individual desires and ambitions stay an intrinsic part of their artistic life. Their modus operandi is ‘horizontal’ rather than vertical/hierarchical.

All four members of the collective speak with enormous respect of the others, and how they all feel drawn to continuing the working process in a spirit of equality and tolerance – which of course sometimes means tolerating differences. Roberto felt, on first leaving Hotel Medea, that he might need some time away from working in the intense intimacy of another collective – but quickly changed his mind. He cites many reasons for continuing the work together, not least a shared interest in ‘The boundary between private and public urban space’. He talks about being highly interested in ‘the friction between these boundaries and what is revealed in their intersection: different behaviours, actions, reflections, omissions, silences…’ He speaks of displacement, of re-choreographing the city through the artistic actions: ‘My presence in this space generates displacements, even if invisible.’

In my week with Cambar Coletivo, I experience a good number of these urban displacements. There is, for example, the afternoon we spend playing Pique Bandeira, a kind of Brazilian British Bulldog chase-and-capture team game that, once it has been tried the ‘normal’ way in the LUME studio, gets taken onto the streets of Barao Geraldo and turned into a massive endeavour staged over a pretty large section of the town centre. An envelope is placed by a plant pot outside a bar on the main drag. A few blocks away, another letter is placed by a lamppost opposite a small park. Team A and Team B compete to try to capture the letter in the other group’s territory. If tagged you have to lie down flat on your back on the ground where you were ‘hit’ and wait to be rescued. You can use your mobile phone to call for help. Thus, at any given time, some members of the group are stealthily stalking people, others are running hard and fast away from their would-be captors, and some are lying on the ground, perhaps blocking a pavement or an entrance to a shop, having a conversation on their mobile. Because the whole game extends over such a large territory, passers-by don’t necessarily grasp any sense of what is being played out – just find themselves encountering some pretty odd urban behaviour…

Not all of our week, though, is spent out on the streets. We also work on developing a solo ‘performance programme’. This aspect of Cambar Coletivo’s work is inspired by their meeting with Brazilian artist and researcher Eleonora Fabião, who defends her use of the term ‘programme’ (rather than, for example, ‘script’) thus: ‘It feels the most appropriate word to describe a type of action methodically calculated and conceptually polished, which generally requires extreme tenacity to be carried out, and approaching the improvisational only to the extent that it will not be tested in advance.’ Performance programmes are thus fundamentally different from devising from an empty space or creating from improvisational games. Rather than improvise around an idea, the performer creates a ‘programme’ – a set of instructions with indications of how to accomplish them. (Noting that a programme could include the instruction: ‘Find a skilled violin player to perform JS Bach’s Violin Concerto in A Minor’ or could ask someone to perform actions they had conceived, or invite viewers to activate their propositions.)

To be honest, I struggle a little at first with seeing what is new or different about this approach, as the ‘performance text’ (as opposed to the scripted ‘play’) has been a mainstay of practice for many years. But after some reflection, I come to what I think might be a good understanding, which is that the ‘performance text’ or ‘script’ is what is created at the end of a dramaturgical process (whatever that process might be: improvising, writing, devising, designing, setting up quests or proposed actions), whereas the ‘performance programme’ is a starting point, a provocation to create.

I am interested in where Cambar Coletivo’s work sits in relation to other artists working in similar ways. Is there any direct relationship, or is it that a number of contemporary artists are influenced by the same things? For example, both Cambar Coletivo and the UK’s Wrights and Sites (also a collective of four artists, who work both individually and collectively) use the process of ‘drifting’ in their work.

James Turpin has heard of the work of Wrights and Sites (mostly through their magnificent Mis-Guides), but says that the use of drifting in Cambar’s work is heavily influenced (as is Wrights and Sites) by the ‘dérive’ of the International Situationists. He quotes Quentin Stevens in The Ludic City: ‘The dérive encouraged situations: the bringing together of aspects of the city which were previously separated in time or space. This convergence created temporary changes in social conditions’. The Situationists’ aim was to understand ‘the urban environment as the terrain of a game in which one participates’ and their dérive highlights that ‘wandering is not purely a matter of chance, but can also be a practice of intentional experimentation, drawing upon the dynamism and the potential for play which was latent in the urban milieu.’ Or as Roberto puts it, ‘the dérive invites us to see the city in a different way’ offering an invitation to: ‘Scour the city for places not yet travelled to’.

When questioned about the company’s influences, all four say that everyday life is their biggest inspiration. As Flávio puts it: ‘Everyday life in all its micro-diversity. I like to focus my attention on life’s most insignificant details, looking at the corners, the edges which nobody wants to see; the unspoken, the undefined, the things lacking clear outline. I like to observe people and their behaviour, which are often contradictory. And this of course includes me too.’ Raquel says: ‘My inspirations start from an everyday sense of what my eyes see; the vibrations that resonate through the skin…’ And for Roberto: ‘Observing animals and children brings me to a very interesting creative state. I like their absolute sincerity; the simplicity of their presence, the way they observe without shame.’

When asked which artists the collective admire, the answers are as eclectic as could be: Joseph Beuys, Pina Bausch, Antonin Artaud, Charlie Chaplin, Guillermo Gomez-Pena, Jacques Lecoq… James and Raquel both cite Mestre Pastinha, a visionary master of Capoeira Angola who was a poet, musician, artist, and writer who helped to maintain important traditions within the art of Capoeira. Roberto mentions Samuel Beckett, amongst a list that includes Hieronymus Bosch and Brazil’s Taanteatro: ‘Beckett I like a lot as he formalises the flow of thought, turns the subject into shape…’ Flávio also highlights the importance of honouring the less well-known current generation of artists: people like Shima and Thaíse Nardim; and Salvador-based Olga Lamas and Lucas Valentim (who are part of the Nucleo Vagapara group). James has some positive things to say about people he admires from the UK scene: ‘Will Dickie. Jonathan Grieve and Nwando Ebizie from Mas Productions. Also Sleepwalk Collective, Action Hero, Joshua Sofaer and his work on audience participation; and the late Adrian Howell’s ground-breaking work with one-on-one performances.’

And like his colleagues, James cites the other artists of Cambar Coletivo as being amongst his influences and inspirations. ‘I think it is important to have that respect and admiration for those close to you and your work, just as much as it is to have an admiration for artists that are perhaps more distant.’

This, perhaps more than anything, is at the heart of the success of Cambar Coletivo: four artists who have, at the core of their work, a shining love of each other and admiration for each other as individuals and as artists. From the outside, it might be tempting to think that such a love affair will never last: the thing is, though, that these four have already been through the growing pains of relationship through the intensity of their experiences together in the seven-year story that was the evolution, development, and demise of Hotel Medea. The extraordinary heritage of this project lives on in the work of Cambar Coletivo, who are making their mark with another challenge to what we see as ‘theatre’ or ‘performance’ practice.

So what of the future? Raquel: ‘The plans are to continue to make, share, create, explore move, search, learn and be involved in an eternal cycle of growth.’ Well, in that is everything, a whole world – and everything within that world shifts and moves and tilts, in permanent playful instability.

For more on Cambar Coletivo’s four artists and their projects see www.cambarcoletivo.com