A large-scale processional performance through the town centre from French maestros Les Commandos Percu, parkour from Belgium’s Be Flat, female clown Margherita Mischitelli from Italy, and plenty of new circus and street arts from across the UK and beyond. Out There International Festival of Circus and Street Arts in Great Yarmouth is back with a bang!

‘I’m most excited to have a full festival again,’ says artistic director Joe Mackintosh.

Last year, the annual Out There International Festival of Circus and Street Arts did go ahead, and was a very successful event (read all about it here in Total Theatre Magazine’s round-up). But there were restrictions: only a very limited number of overseas companies were programmed, and the traditional Saturday night processional performance through the town didn’t happen.

‘It’s the thing people are most excited about,’ says executive director Veronica Stephens. ‘Everyone in Great Yarmouth loves the parade, which ends with a big spectacle. In the past, we’ve had Générik Vapeur and Transe Express – and this year we’ve got French percussion and pyrotechnics company Les Commandos Percu.’

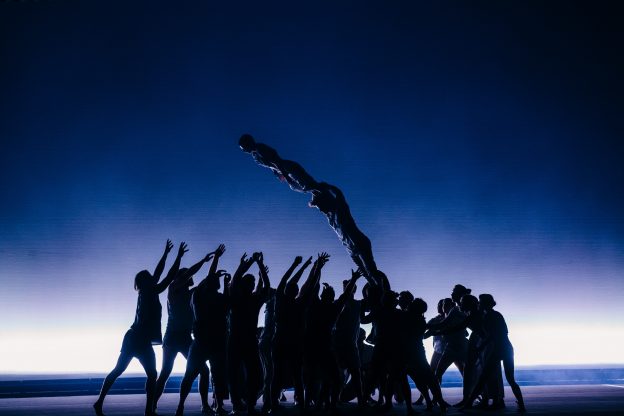

The show in question is called Silence, perhaps ironically, and features a cacophony of drums with musical pyrotechnicians storming the streets: post-apocalyptic and rife with animalistic sound and raging fire… although it’s all about the moments of silence in between, say the company. The procession will move from St George’s Park, along the seafront, and end on the beach.

The festival have been in discussion with Great Yarmouth Borough Council about ways to prceed with this event in the light of the demise of Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II. They will now include a dedicated announcement and a two-minute silence within Silence as a tribute to the Queen, with the National Anthem sung at the end of the show in honour of the new king, Charles III – what Joe and Veronica describe as ‘the biggest tribute moment of the festival, a poignant and appropriate shared point of reflection’. Les Commandus themselves have been passionate about adapting and dedicating this special performance. It is the ideal vehicle for tribute, as it is being created with local people working with the company during this coming week and in the words of the company themselves: ‘This will be the most poignant Silence that we have ever performed – we will be honoured to make this tribute with the community of Great Yarmouth and also as a token of the deep respect held for the Queen by the people of France.’

Silence is one of a number of shows using Great Yarmouth seafront this year. ‘It’s nice to be spreading out,’ says Joe, ‘making much more of the seafront and the beach. Last year was the first time we really used the beach – we had Gorilla Circus as the finale. This year, we’re extending it, putting more on there…’

Other shows scheduled for the seafront area in this year’s festival include Timeless by Joli Vyann, a dance-theatre piece set in and around an interesting revolving ‘egg timer’ structure, which is doing the Outdoor Arts rounds this year as part of the Without Walls consortium.

This show was created at The Drill House, Joe says. Which is an opportunity to mention that Drill House is an arts centre and more: a creation centre that is Out There Arts’ year-round hub; supporting UK and overseas artists, providing making and rehearsing space for emerging and established artists alike. Another Out There Arts supported artist is locally-based Matthew Harrison.

‘We’re very pleased to be presenting the 100th outing of Actual Reality Arcade, which we supported from the start, and which has toured successfully across the country for a number of years,’ says Joe. ‘Matthew is a visual artist and a filmmaker, and we encouraged him to think big, to move his work up in scale,’ adds Veronica.

The show is a lovely, tongue-in-cheek, real-time re-creation of some classic video games, which are given a fairground-inspired makeover: a ‘life-sized interactive game-zone for all ages, inspired by classic arcade games where you play for real’. Harrison has subsequently been commissioned by gaming companies to create additional models for other games. Last year, he also created a new work, Community Chest, which was presented at Out There Festival 2021. ‘His is a great local success story,’ says Veronica.

So other than those two, what else might we find on or near the beach in the 2022 festival?

‘There’s Vanhulle Dance Theatre,’ says Joe. ‘I’m interested to see how they are! The company is led by a Flemish performer new to the UK. She was previously in Icarus, and this is her first appearance at Out There Festival with the new company.’ The show is called Dovetail, a UK premiere.

The other big drive for 2022 is the extension of Out There’s community engagement programme. Always a vital part of the organisation’s work – they are firmly committed to working with communities in meaningful ways – the 2021 programme saw the festival reaching out beyond the town of Yarmouth into the satellite towns and housing estates, where residents are traditionally less likely to be engaging in the arts. Last year there was an evening of events in Cobham, and additionally the involvement of young Cobham residents in Puppets With Guts’ Big Lips show as community dancers. This year will see a return to Cobham, but also a reach out into communities from the Magdalen Estate in Gorleston and Middlegate, Malakoff and Blackfriars Estates. This time round, a great number of Out There artists will be involved.

‘Les Commandos will be embedded in the community, recruiting and workshopping with drummers from the estates,’ says Veronica. All of this work will come together on the Saturday night for the big parade (although of course also having its own stand-alone merit within the communities worked in).

‘Belgian companies Be Flat (parkour) and Tripotes La Compagnie (circus/teeterboard) are going to be doing animations in and around the estates in the week before the festival,’ she adds. ‘And we’ll hold tea parties in the estates in the run up to the festival.’

Also involved in the outreach programme will be Toussaint to Move who will be presenting Beatmotion Mass, running dance workshops within the community, and integrating professional and community performers in work presented. Out There Arts will be working with Creative People and Places partners Freshly Greated on this extensive outreach programme.

‘Freshly Greated have the resources to really be on the ground,’ says Veronica. ‘We can bring in the artists, and they are there, making the connections. Creative people, creative communities – that’s the whole purpose. And we incorporate participants’ feedback into the work, which is good for the festival…’

Joe also flags up another area the festival is working in and on, in the town centre:

‘We’re putting interventions and small shows on Regent Road – we have done stuff there in the past, but we’re making more of it this year.’

For those who don’t know Yarmouth, Regent Road is an oddly old-fashioned pedestrianised street that specialises in gift shops, unintentionally retro cafes and sweet shops, and (oddly) Elvis memorabilia.

‘It has a flow of people, but unlike the people in the park, they won’t be self-identified festival go-ers!’ says Joe.

So, Jon Hicks will be there in his prophesier persona, The Visionary, he of ‘fantastical wisdom and mystical powers from beyond knowledge’. He will possibly be convincing some people that he is, as Joe puts is, ‘a genuinely strange preacher who has just rocked up in Yarmouth’. Predictions, illusions, proclamations and panic will abound.

There will also be a number of musical acts along Regent Road, including the legendary Dutch glass-player Roger Kappers with The Glass Grinder, and Japanese one-man-band Ichi.

Oh, and talking of Elvis, the new Spitz and Co show Blue Hawaii features an extremely good Elvis impersonator, I’m told…

There’s also an interesting new venture from Working Boys Club called Serving Sounds, which is ‘a multi-sensory sound installation that serves bass rather than beer’ and will be appearing at pubs around Yarmouth over the festival weekend. It’s led by Jason Dupree from Living Room Circus – but is a very different kettle of fish, allowing Jason to step aside (for a while) from experimental circus-theatre to reflect on and explore his own working-class roots.

Meanwhile, over at St George’s Park, and on the streets in and around it, we are likely to find an eclectic mix of top-quality circus and street arts companies and artists.

This year’s programme includes slackrope performer Pete Sweet’s new show Foolish Doom, presented under the company name Tiny Colossus, which Joe describes as ‘ a big departure – a two-hander, a costumed puppetry-mask show about climate change that has been developed at The Drill House. I’ve seen bits of it, but not the full show…’

Joe also flags up Margherita Mitischelli: ‘A very good solo woman clown/circus performer. There are far fewer women than men street performers – she is pretty brilliant and not well known in the UK.’ Her show Amore Pony promises a journey of discovery of the feminine spirit, between ‘fairytale suggestions and grotesque implication’ – expect unstable equilibriums and talking mini ponies!

Then, there’s Butoh dance company Cie De Ta Soeur, whose Monta Tanto draws on folklore and popular culture, inviting us to return to ‘a playful nature, wonderful diversity and the essential’. Expect the primordial and other worldly.

‘Good to be going back to having some odd stuff, ‘ says Joe, ‘It’s so strong and so different. Audiences might be puzzled, but they’ll remember it!’

He’s also pleased to be programming Ishariah Johnson, aka Stormskater – one of the UK”s best known inline skaters – an online sensation who posts videos of herself skating in public spaces in London, but who has never (as yet) done a show in a street theatre festival ‘We’re a bit nervous about it,’ says Joe ‘but this is us making the effort to find new talent; to reach across to people outside of the usual outdoor arts circuit and say “have you thought about…”’

Another interesting addition to the programme is Qwerin, a Welsh company who combine traditional and contemporary dance, all with a queer sensibility.

This brings us neatly to reflect on another new initiative for Out There Arts, the Four Nations Partnership which sees the organisation (representing England) working with Surge (Scotland), Spraoi Festival in Waterford (Ireland), and Articulture (Wales) to bring a number of emerging artists/companies from all nations of the British and Irish isles not only to Out There Festival but to other festivals across the UK and Ireland. One of the English components of this group are Beside Ourselves Collective with their new show, The Roving Court – a new, interactive, pop-up street theatre show in which a Judge on a mobile bench tries adults for their childhood crimes, a barrister seeks to defend them ,and children form a Jury to help the Judge hand down comedic punishments.

Another interesting young British company appearing at Out There 2022 are Farm Yard Circus, whose eponymous show promises to ‘bring the cows home with old-time tunes and raucous rhythms, and a juggling suite composed of hay bales, wheelbarrows, a tractor tyre, and even an old scarecrow’.

They are mostly graduates of the National Centre for Circus Arts (formerly Circus Space) or Circomedia. Joe sings their praises thus: ‘There are seven of them, and with a nice mix of skills and disciplines. We were keen to support them as this is the sort of circus show we struggle to find in the UK – with this scale and a decent range of skills. There are very few of them. I can name 20 companies of this sort from Flanders!’

At the other end of the experience spectrum are a number of veteran artists included in the programme. Chris Lynam, the infamous iconoclastic clown ,brings The Beast of Theatre to the festival, promising ‘indescribably wild and wondrous physical comedy’.

Will he have a firework up his bottom, I want to know. Veronica replies that she doesn’t know, but there’s a good possibility that he will ‘get his willy out’. You have been warned.

‘It’s great to have the balance of fresh new talent alongside that core of amazing, really experienced street performers,’ says Veronica.

Talking of which, Akustrik, led by longstanding street theatre favourite Ali Houiellebecq, are bringing D.o.G (Department of Gruff) to Out There – an all-singing all-playing comedy pastiche band in complete dog regalia. We are invited to ‘howl along to well-loved tunes dished up by this pack of versatile mutts as they ramble and shamble along the streets of Great Yarmouth.’ They will also be taking part in the opening night Party in the Park on Friday eve.

Then, there’s Sarah Munro, another ‘veteran’ – former co-director of the late great Insect Circus. She’ll be premiering her new installation, Miss O’ Genie’s Dazzling Dollirama, in which Miss O’Genie and her Damnable Dolls present an alternative approach to a coconut shy, giving us a chance to throw things at famous misogynists.

So there we are – a veritable cornucopia of festival goodies all lined up and ready for the off.

‘There’s serious stuff, funny stuff; brand-new stuff, old-school stuff,’ says Joe in conclusion. ‘Something for everyone!’

Featured image (top of page): Les Commandos Percu: Silence. Photo Veronique Balege

Out There International Festival of Outdoor Arts & Circus takes place Friday 16 – Sunday 18 September 2022 in Great Yarmouth. For the full programme, and further information on the artists taking part, see www.outtherefestival.co.uk

The festival includes a day for professional artists, producers and presenters. Catch Up takes place on Friday daytime and there are also workshops, an Artists Marketplace, pitching sessions, and networking opportunities on Saturday and Sunday mornings.

Total Theatre Magazine will be presenting a session on Saturday morning called Total Theatre Talks: Stop Press! An informal workshop for artists, producers and anybody else interested in reflecting on writing about outdoor arts & circus, and on ways of publicising work.

For more information and to register for the professional programme, see https://outtherearts.org.uk/catch-up/