Doctor, doctor can you hear my heartbeat? It goes boom diddy boom diddy boom diddy boom – well goodness gracious me! Yael Karavan’s assumed character at the start of Somnambules has something of the classic Sophie Loren about her, with her shiny black hair, seductive eyes and wiggling walk. Her white-coated doctor friend, played by Tanya Khabarova, is heralded by a harpsichord riff – this, the gleaming bald head, and the sinister smile, give him/her an air of sci-fi menace. Let the experiment begin…

NEXT! Together they flirt and dance, and delve ever deeper into their shared psyche(s), a Jungian sea of unconscious fears and desires informed by archetype and icon. Binary divides and dichotomies abound. They morph and change, they are animus and anima, war and peace, good and evil, black and white – a pair of heavenly (or devilish) twins joined at the hip, at one point fighting to assert their own individuality, at another trying to merge into one. Manipulating and manipulated, swapping roles of puppet and puppet-master, creating an alchemical mix that bubbles and boils until eventually exploding, resulting in a plastic beach of distressed bubblewrap, bin liners and rain ponchos occupied by our two characters, who would seem to have regressed (or perhaps progressed) to a negative print of Tellytubby land, all high-pitched voices and silly party games, a king and queen in paper crowns.

NEXT! Rewind the clock. There are hands that become fluttering birds, a Faustian contract signed in blood, a baptism of fire, toy guns, robotic dances, a Pieta, a wild waltz, a tongue-in-cheek Isadora Duncan tribute. There are veils, and brides, and confetti. There are alchemical signs, tarot cards, skulls. There are mirrors, and shadows, and there is a moon. La Luna, la Luna – you shine so bright tonight.

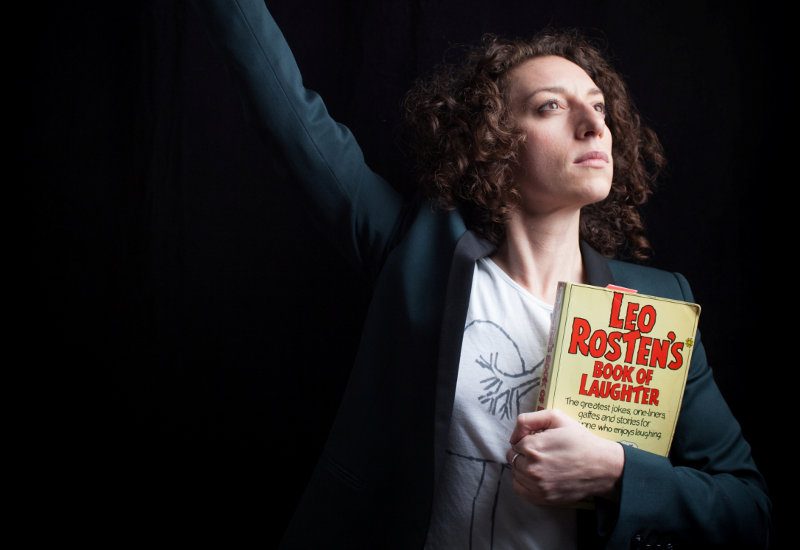

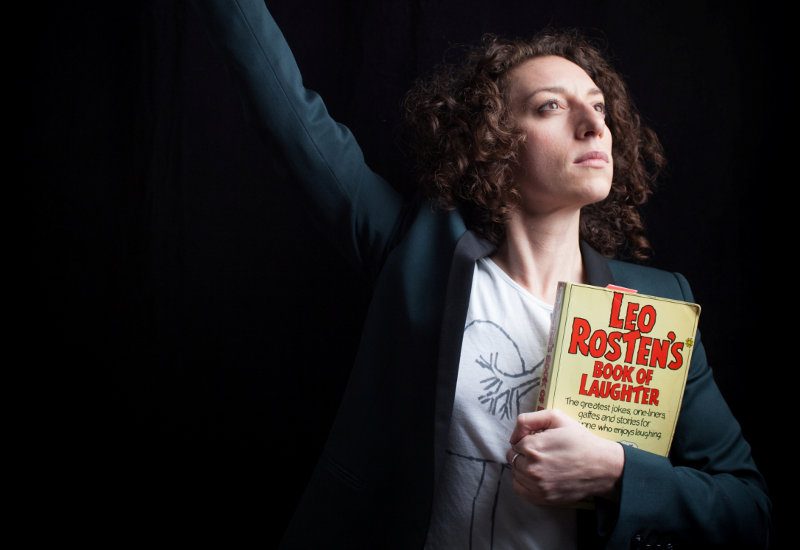

The visual imagery of this piece is rich and deep. The physical performances are stunning: Tanya Khabarova and Yael Karavan have a shared history as members of multi-award winning Russian ensemble Derevo (of which Khabarova was a founder member, and in which both performed for many years), and the performances are of a quality rarely seen anywhere. A match made in heaven indeed. Or brokered with the devil, one or the other. The lighting design is sophisticated and beautiful, the sound an extraordinary mix of musical and sonic elements from many different places and times – from chirpy cuckoo clock to bombastic church bell; from nursery music-box tinkle to war zone bombardment.

It’s not a perfect show. There are moments that sag a little, the worst being a paean to ‘Destiny’ in which the words of a pre-recorded voice are mouthed by Yael Karavan as she sits cross-legged in front of a mirror. It comes early in the show, and it drags the energy down just as it should be lifting. Yes, the ‘destiny is not a matter of chance, it is a matter of choice’ question is an interesting one, but I would have preferred it raised in some other way. There is a beautiful shadow-theatre sequence, but played off-centre rather than straight-on, so some of the audience see behind the screen and some don’t. I suppose as the shadow work rather cleverly references the Wayang Kulit puppet tradition, it is fine to see the behind-screen workings (as one would do in Bali), but it never the less seems a little odd.

I sometimes feel that the show would have benefited from an outside director or dramaturg, or at the very least an outside eye: the relationship between Khabarova and Karavan is so close, so intense, that the audience sometimes feel a little like voyeurs looking in on it, rather than being drawn fully into the game.

It should also be noted that the show has moved so far away from the original content and structure of the piece of the same name presented at Brighton Festival Fringe 2012 (and reviewed there by Total Theatre) that it has, in essence, become another work altogether.

Somnambules is a show that I’ve seen twice in its current form, and it is a show you need to see twice. I know that is a contentious thing to say, I know some of you will believe that theatre should work on one viewing, but there is so much to view that a second look is strongly advised. It is an extraordinary adventure, chock-full of mythical allusion and theatrical illusion. A very full, and totally full-on, spectator experience.