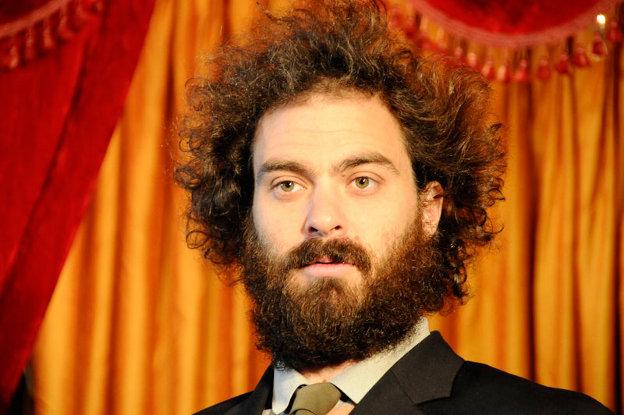

Growing up can be a compromise. In the relentless drive towards adulthood it can be so easy to forget some of the most important elements of being a child. In some small way Dr Brown, with his shows Befrdfgth and Dr Brown Brown Brown Brown Brown and his singing tiger, is helping us to reconnect with the most crucial of those lost pastimes – the importance of being silly, the joy of play.

Befrdfgth takes its audience on a subtle journey. Beginning with Dr Brown (Phil Burgers) ludicrously peering out at the audience from behind the curtain, even kicking them as they pass. This unsettling start continues as he makes his way into the audience in a ridiculous fashion, hidden under a large curtain, to steal an audience member’s scarf. The poor victim is then encouraged to get it back; it’s not so easy of course and a game ensues, ending with the member of the audience being dragged behind the curtain. The audience are laughing but it’s all so unsettling, and when the lady returns to her seat, visibly shaken, the atmosphere has a very peculiar tension. It all increases as he comes into the audience again and I can hear the collective wish being chanted in unison with the collective mind of the audience, ‘Please not me, don’t get me’.

But in a fantastic twist of tone Burgers emerges slowly from the curtain with his hands in the air and a fearful expression on his face. He seems to be mouthing words silently and shaking his head as if to say, ‘I’m sorry I have no idea what I’m doing’. Without ever uttering a word he then moves through a series of irreverent sketches, all executed in excellent mime, and all of them entirely ridiculous; a beggar woman who asks for a coin but has no pocket to put it in, a man who gets inside a cow then falls in love with another cow who bears him a child.

As the show goes on the realisation slowly sweeps over the audience – it’s OK because he’s playing, he’s just being silly. Then the audience relaxes.

He asks the audience to play too: we have to provide the sound effects to his sketch of a ride through the park. As our collective comfort grows we feel the urge to play along, to be silly and to laugh at ourselves. Burgers himself couldn’t help laughing as he asked the audience to all copy him in speaking gobbledegook – a wonderful moment of connection between performer and spectators.

This freedom to play is then taken to another level as he gets a member of the audience to take a role on stage as the son of the cow from the previous sketch. He, the audience member, becomes more and more involved as he is asked to perform a sketch on a bike in the park while we provide the sound effects and Burgers takes a seat in the audience.

This is a real highlight of the show as we watch someone playing, with complete freedom to be silly in front of a room of strangers. It is entirely liberating, a shared game that we’re all playing.

Before we know it we’re at the end, gentle music is playing and Dr Brown is preparing to leave. We see him humbly thanking each member of the audience who got involved, obviously very appreciative that they agreed to play. He blows kisses at them in his gratitude.

We then begin to feel a strong emotional connection to this man whom we all feared just an hour ago. I even hear a gentle ‘awww’ from the audience as he mimes giving us all a hug, and I feel we’ve all actively taken part in something special and worthwhile as the show draws to a surprisingly poignant close. The experience was entirely unique, utterly inspiring and won’t be long forgotten.

Dr Brown Brown Brown Brown Brown and his singing tiger, his show for children, is a more tame version of the same experience. Joined on stage by his singing tiger (Stuart Bowden) who helps to translate Dr Brown’s silence, the focus here is much more on being silly.

We join Dr Brown as he goes through his daily chores from breakfast through to riding his bike, his favourite thing to do. Each sketch is so wonderfully silly and executed with such great timing it has the audience of young and old in stitches. Stuart Bowden does an excellent job of softening what could be quite a scarily bearded man with his ukulele and constant singing.

One of the best elements of the piece is of course the audience interaction. He likes to pick on the dads and gets them to mess around on stage which delights the children. At one point he invites all the children in the theatre to help him put on his Wellington boots. The kids crowded onto the stage in glorious anarchy; it was great to see so many children involved with the performance.

The climax of the show involves the long awaited bike ride. Dr Brown decides he wants to do a stunt over a very tiny ramp. Again he invites all the children on stage to lie down in a line as he tries to jump over them all. Before we know it there are twenty or so children lying down on the stage heading right out the door. Just like his adult show the whole audience are a part of the game, and the ridiculously silly pay off at the end of the stunt completes the play.

It’s so very inspiring to have a successful performer at the fringe so dedicated to such a simple and joyful thing. Both his adult and his children’s shows are a monument to the importance of being silly. Whether you are a child who embraces that worthwhile virtue, or an adult who has long forgotten it, Dr Brown is reminding us all of its joyful importance.