There is a heading used in the programme accompanying NDT’s current run at the Edinburgh International Festival: From rebellion to eminence. The words draw reference to the 1959 origins for the company when 21 members of the Nederlands Ballet became positively charged by the potential and promise of experimentalism over classicism and so tore themselves from Sonia Gaskell’s Amsterdam base to set up camp in The Hague.

There, stoked by the work and teachings of, among others, Merce Cunningham, Martha Graham and José Limón, the new company set about a campaign of exploration and growth which saw them evolve into the position they now continue to sustain – one of the most successful contemporary dance companies in the world.

All the more reason to find it so curious then that of the three discrete parts that form the 2017 Edinburgh programme, two of them should be so conservative. Which is not to take anything away from the quality of the dancing. The elegance, fluidity and clarity of the performances throughout was never less than heart meltingly beautiful. But there is something concerning the underlying narratives that led the opening and closing segments to feel, in a sense, unrealised.

In the opening, Shoot The Moon, premiered in 2006, a revolving set of three empty rooms unspools three snapshot stories of boy-girl relationships. First passions, working stresses and interminably repetitive routines impacting on love, the endless peering through doors and windows into other lives in the hope of being invited into something fresh, dangerous, and probably doomed. Sol León and Paul Lightfoot brought pin-bright clarity and efficiency to both the choreography (set to the second movement of Philip Glass’s Tirol Concerto) and the set, but the tropes felt familiar and so it was the technical virtuosity alone that carried the piece.

The closing piece, Stop-Motion, again choreographed and with a devised set by León and Lightfoot, was altogether more ephemeral. A series of brief vignettes set to a pick ’n’ mix selection of Max Richter’s trademark melancholic short works, each with its own heaped spoonful of sentimental sugar, saw seven dancers enact various aspects of departure and separation. The ephemerality of the proposition took on an almost literal shape as the dancers swept through chalk dust and, presumably, became as dust themselves.

In between these two works was The missing door, an altogether more challenging proposition. And one that was ultimately more rewarding. Here, NDT handed the reigns to the Argentinian born co-founder of Brussels’ Peeping Tom collective, Gabriela Carrizo, who led not only on choreography but in set and costume design. (Peeping Tom associate artist Raphaëlle Latini is also part of the creative team.)

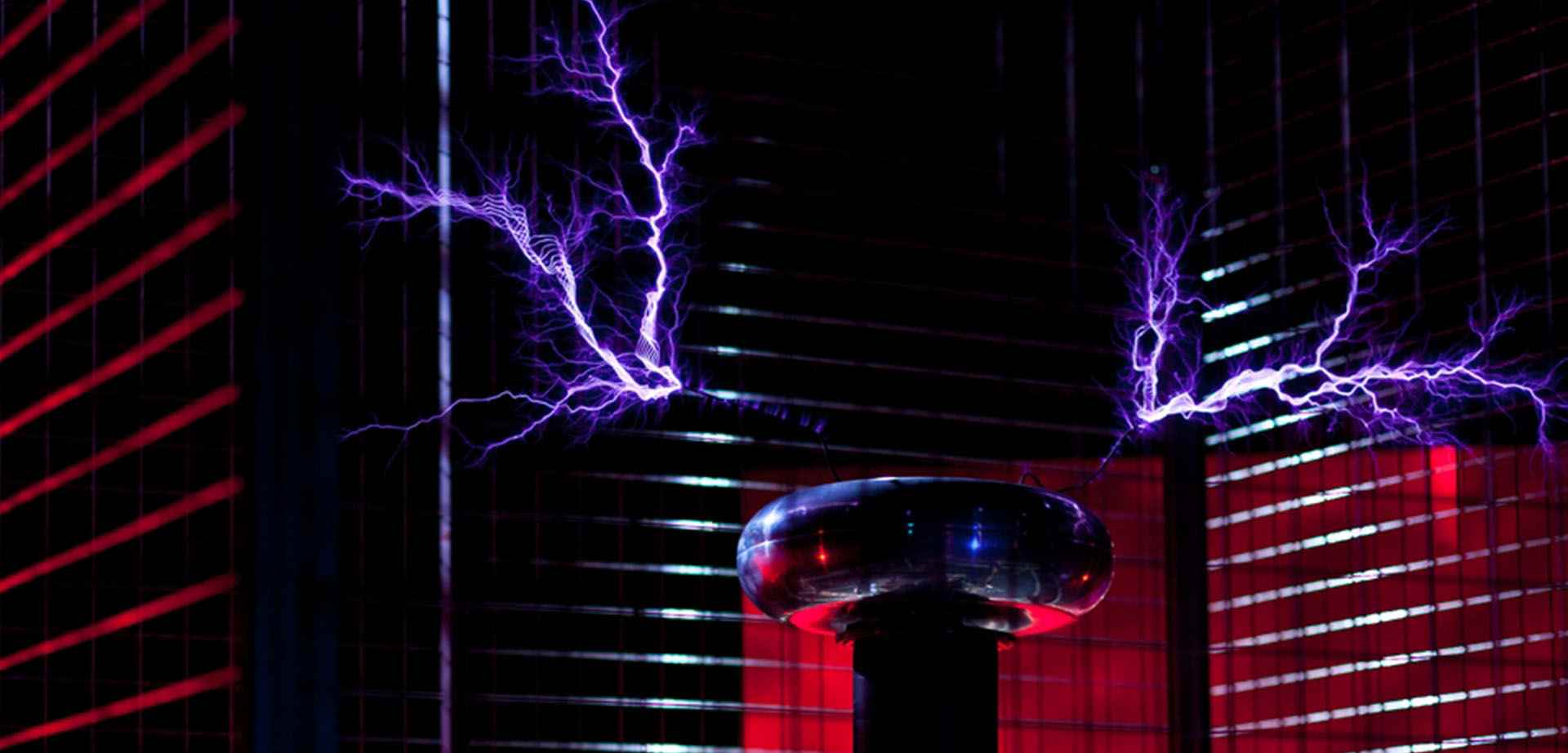

The risk taking became apparent right from the start. Characters on stage, yet off set, adjusted arc lamps, furniture and props. A man with a bloodied shirt lay motionless, presumed dead, at the heart of a two-wall set. Not quite innocuous sounds, peppered with static crackles, amplified in the sense that one imagines the borderlands of mental breakdown to be magnified and distorted.

A man begins wiping the floor clean of blood, before the cloth escapes his grasp and skitters across the floor. Over the twenty-five minute duration of the piece we are plunged into parallel moments of time: revisited, twisted, mutated and tossed to and fro between the twin logic of memory and dream.

A figure lives through, and around, the last moments of life, and the dizzying spectacle is of Carrizo examining the moment as though through a prism offering multiple perspectives on the scene. The borders between dance and physical theatre are savaged and thrown aside. The fourth wall is rent by buzzing stage lights and shaking sets, a storm burst through a door and sends the cast scattering across the floor, and in one beautifully grotesque moment a dancer seems to decapitate herself through her execution of a double back bend. Resolution, as such, only arrives when the spectacle loops completely on itself and we are back at the beginning, wiping the blood from the floor in a near empty room where death seems to be the only real tangible presence.

Special attention has to be given to composer Raphaëlle Latini (who when not working with Peeping Tom is a Paris-based DJ) who handled the material with style and audacity in equal measure, turning time into a malleable, liquid medium that could be stretched, glitched, eroded, sampled and reconfigured, and in so doing providing not so much a musical ground upon which the action could be cast and contained – but an equally active, dynamic and challenging presence that fought for and against each twist in the physical narrative with compelling urgency.

This, I have to imagine, is the spirit in which NDT was formed. And whilst acknowledging that it may only be a personal prejudice affecting my ability to entirely surrender to the full programme of smoothly executed, impeccably stylish performances, I did sense a mischievous acknowledgement of how far this towering presence of a company has come from the brash and righteous bravado of its inception. Towards the close of the third work, when all the chalk dust had settled, the outsize projection screens rolled away, the heavy curtain blacks were tied and lifted to expose the extensive backstage guts of the Playhouse, and the lighting rig began to descend silently from behind the proscenium. The dance, meanwhile, played out to the end in the now naked theatre space. It felt very much like a stripping away of artifice, of rich clothing, reputation and ample resource. NDT returned, in perhaps the most subtle piece of poetry in the programme, to the essential core of their business; the supple beauty of the human body and the remote possibilities of what can be achieved with it when alchemically charged with music. A primal spirit here captured fantastically by Carrizo and Latini.

Featured image: Nederlands Dans Theater / Gabriela Carrizo: The missing door. Photo by Beth Chalmers.