Making his British debut, young circus director Yoann Bourgeois’s He Who Falls (Celui qui tombe) is as intelligent, inquisitive and, most importantly, deftly-pitched a performance as you’ll find in any British theatre this year. These are the kind of performances that the London International Mime Festival is for, and, in the absence of a French level of adventurous, sustained, and systemic funding for the development of circus in the UK, it is likely to be one of the few means by which British audiences can enjoy this type of work on home soil.

Making his British debut, young circus director Yoann Bourgeois’s He Who Falls (Celui qui tombe) is as intelligent, inquisitive and, most importantly, deftly-pitched a performance as you’ll find in any British theatre this year. These are the kind of performances that the London International Mime Festival is for, and, in the absence of a French level of adventurous, sustained, and systemic funding for the development of circus in the UK, it is likely to be one of the few means by which British audiences can enjoy this type of work on home soil.

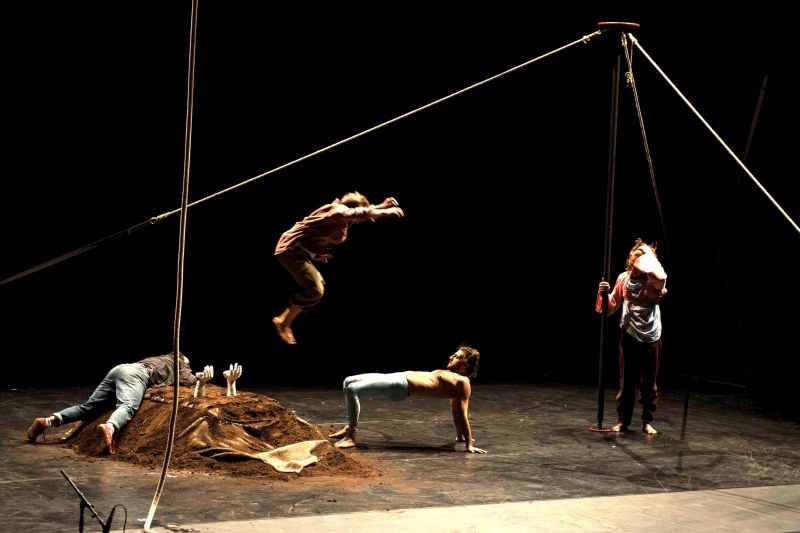

He Who Falls begins from an artfully simple premise: subjecting the mass of the human body to forces generated by a single object. In this case the object is a simple, but very large, wooden platform moving about its various axes.

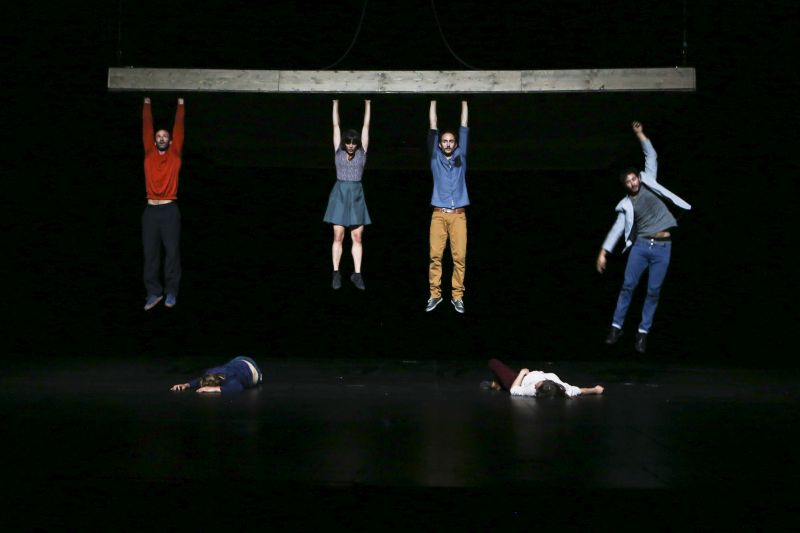

First this platform begins to tilt. The six performers’ bodies that lie prone begin to slide. The platform changes the direction of its tilt. The bodies react to this change, first slowly and then more quickly as the incline increases. The bodies appear lifeless, sacks of meat and bone, sliding ever closer to the edge – to oblivion. Then… a performer stands, they attempt to fight the forces acting on their body. They try to resist. But they can’t overcome the forces. This fundamental struggle sets the tone for the entirety of the work: that the performers are subservient, no, subject, to the object – they are literally forced into action.

The platform settles to the horizontal, and then it begins to spin. The performers attempt to balance, to stay afoot the spinning square of wood. And so continues the pull and push of the object against these six figures. Each time the platform changes its behaviour, so the performers have to learn to adapt and to survive.

This platform, which seems to have a life of its own, might also be a not-so-subtle nod to Bourgeois’s collaborator at his Atelier du Joueur, Mathurin Bolze’s 2010 work Du goudron et des plumes, which also took place on a giant, suspended wooden platform. But where Bolze’s work is strident and replete with tricks, Bourgeois’s work is elegant in its simplicity. In this simplicity there are clearer sympathies with the work of fellow Frenchman and pioneer of circus Aurelian Bory (Compagnie 111). He Who Falls recalls the manipulation of the different angles of a single plane in Bory’s Plan B, and the apparent autonomy of a robot arm in his compelling Sans Objet. And, not least of all, the ways in which in Bory’s work simple mechanics are transformed into scenarios of striking beauty and sadness.

Just as Bory forensically investigates a single idea in each of his works, so does Bourgeois as he (literally) winds the idea up and lets it run. Simplicity is Bourgeois’s watchword, and it becomes a treat to see the simple, but stirring consequences of human bodies resisting the centrifugal forces of the spinning platform. At times the performers walk, at others they run, or tumble over one another, and then suddenly they freeze – as if caught in suspended animation. In this moment of repose the performers strikingly embody what Russian director Meyerhold would call a rakurs, a position that contains within it ‘the perspective of the continuation of the action’ – even in stillness they are still moving. It is this use of rakurs that generates the poetic heart of the work, as it allows time to absorb and process the moments that have come before and to literally feel within our own bodies the momentum of the bodies in space.

Bourgeois’s work then is essentially a kinetic sculpture, in which physical forces are manifested in the performers’ bodies, and then with careful and delicate use of their gaze and rhythm these manifestations become relationships. It is with these relationships that Bourgeois shifts the work from ‘mere’ spectacle to poetry. There is the group, there are partners and there are individuals – but these are never sustained for long – as the external forces push the performers into new positions, into new decisions about how to react to the offers the platform makes.

But in spite of the scale and magnificence of the object, the most important and rewarding aspect of the poetry of He Who Falls is the quality of restraint that Bourgeois and the ensemble apply to the work. There are few recognisable ‘tricks’ in the entire piece, and those that there are, are almost smuggled in behind a gentle and reflective quality. Instead of showy display the ensemble execute their responses to the force with an apparent casual physicality and a sensitive playful response to the sensation of these forces. It is as if any of us could do these things – if the forces were acting upon us.

In some ways even the spectacular nature of the wooden platform is elided over, and it is only when Bourgeois directs our attention away from the ensemble to the technicians as they change the settings or move the mount on which the platform sometimes sits that the technical complexity of the object becomes clear. Yet, because the technicians’ actions match the pragmatic and prosaic attitude of the ensemble, although we see the workings of the beast, there is still an attitude that this is how things are, and that we don’t need to make a fuss about it.

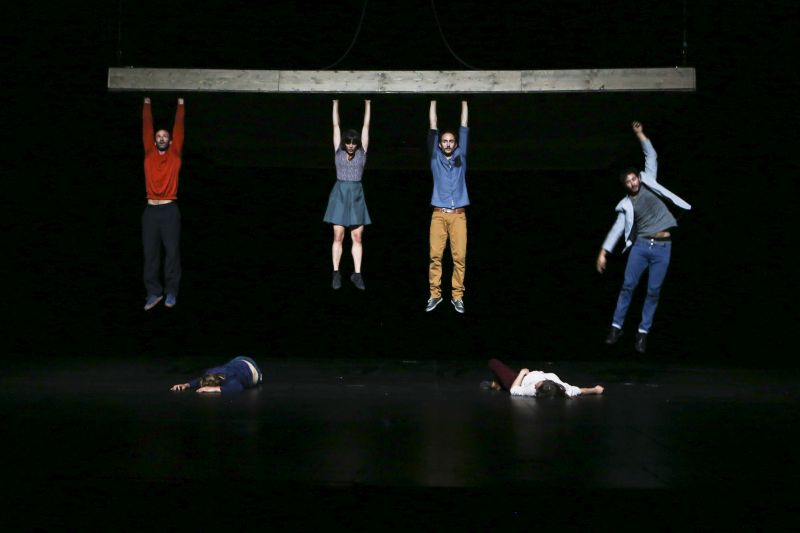

Through this careful and deliberate use of restraint Bourgeois manages to locate the power of the physical work in its possibility of being read as a simple example of human beings facing the arbitrary and uncontrollable orbit of the world. And, rather than embellishing or heightening the struggle of human beings he just presents the simple struggle to stand upright, to balance, or to move from one position to another. It is a clear elucidation of Peter Brook’s maxim that it only takes an actor to walk across a stage for theatre to happen. So the work is most powerful when the images are the simplest: a swinging platform striking, dragging, and then lifting the performers from the floor, five performers trying to lift their ‘dead’ comrade onto a rising platform, and finally those same five performers hanging by their hands for as long as they can from the platform’s base – only to drop, one-by-one, into the darkness below. It is in the moment that the idea reaches it awful conclusion – that no matter how much we can negotiate the forces on our lives, at the end there is only one outcome.

Torn invites the viewer into a private place. A place where madness is close, but will never be called such because this kind of madness is, perhaps, common to us all, and remains contained in moments of loneliness. There is no witness to call us mad.

Torn invites the viewer into a private place. A place where madness is close, but will never be called such because this kind of madness is, perhaps, common to us all, and remains contained in moments of loneliness. There is no witness to call us mad.