How far would you go to protect yourself, your family, your country? Does the end justify the means? If you are acting under orders, for the greater good, does that absolve you of any harm done to individuals along the way? Is it OK to be a whistleblower? Is it OK to spy on your friends and colleagues? Where, and to whom, do your loyalties lie?

I remember the childhood playground conundrum: if you had a loaded gun, your friends asked, and you were in a room with Hitler in 1939, would you pull the trigger. I always said ‘no’. I understood the logic of ‘yes’ but I believed that you must follow your own moral code regardless – and if you believe it is wrong to kill, it is always wrong to kill. Later, in adulthood, I’ve revisited that question many times. I think my answer would still be ‘no’. But I’m not so sure. Would you pull the trigger to save your children’s lives, say? Yes. Any mother would say yes. There are few moral absolutes.

The means-to-an-end question is at the heart of many works of literature and art. That exact scenario – shooting Hitler, changing history – is explored in Kate Atkinson’s Life After Life. The De Toro film Pan’s Labyrinth brought us the moral dilemma of people fighting fascism who find themselves behaving with the same cruelty. John le Carre wrote eloquently about the life of a spy, and the daily moral dilemmas of living a double life. The petty betrayals in his stories are always the most harrowing.

So, even if you wouldn’t kill, would you lie? How do you fancy yourself as an undercover agent? What, for example, if you were given the opportunity to undermine the activities of the far right? How far would you go? Can you make the grade?

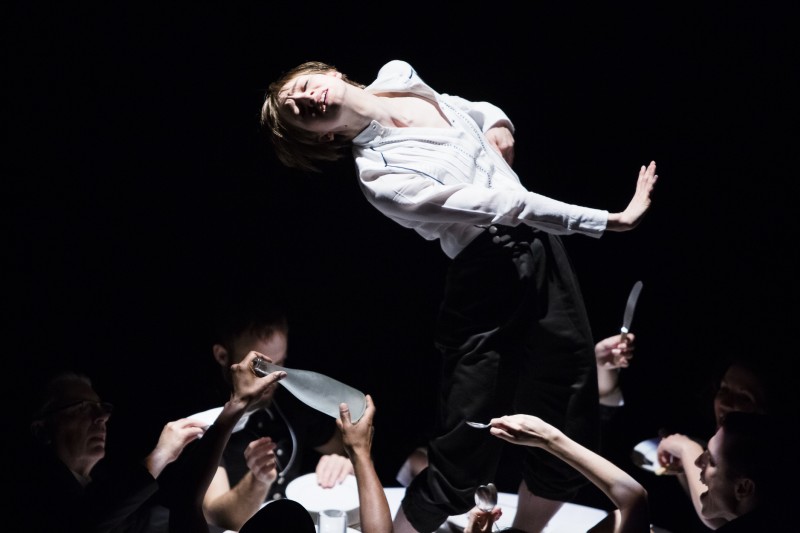

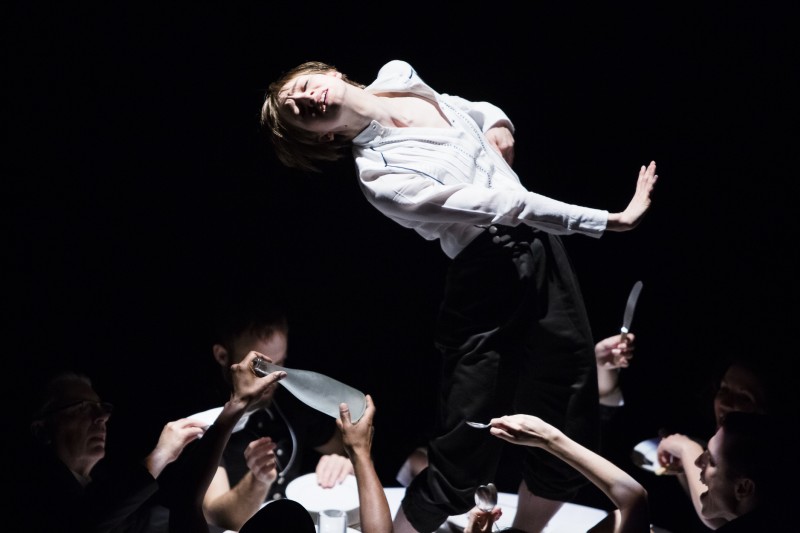

Operation Black Antler is a – well, I was going to say site-responsive, but I think situation-responsive might be more accurate – show that explores the world of the undercover agent infiltrating a new right-wing organisation. It is participatory theatre to the max – and as such, is something of a Marmite show. You either throw yourself into the scenarios offered and enjoy it, or you sit on the sidelines feeling uncomfortable.

‘You’re very good at this,’ says the man I’m working with in my ‘unit’ of three. He’s our communications officer (or ‘on coms’ as our police handler Gemma would have it). Gemma’s a tough cookie, totally believable – I feel pretty nervous when she tests me on my cover story and breathe out when I pass the test. I’ve taken her advice: it’s easier to lie if you just distort the truth rather than invent something totally new. So I’m an English teacher who went to Teacher Training College in South London. Because 40 years ago, that was true, so it is easy to play the lie. I’m enjoying myself in my new identity. I’ve located the person I’m supposed to befriend, and it’s all going to plan. But the two people who make up the unit with me aren’t having fun. They don’t like role play. They want out. Perhaps, I think, this is a show that only appeals to actors. Professional liars. But no, in the debrief session at the end I meet fellow performers who felt slightly uncomfortable in their roles, and people who had never done a day’s acting in their life completely happy to throw themselves in head-first with great gusto.

Operation Black Antler aims to get its audience talking about the issues raised by such cases as Edward Snowden, the Wikileaks affair, and the recent terrible revelations that certain UK undercover policemen were ‘deep swimming’ so far in that they formed relationships with women they were spying on, even having babies with them to maintain their cover. In this aim it most certainly succeeds, judging by the animated conversations in the debrief session that ends the show.

It is a show that is hard to assess critically as each experience is an individual one, and so much depends on the audience member’s willingness (or otherwise) to engage with it all. I enjoyed the game, and got a lot out of the experience.

If I have a criticism, it is that the show is actually a little too safe, (for me personally, anyway). There was a moment when I found myself being recruited as a right-winger, and I feel I could have been grilled far more rigorously about my beliefs by the man I had been taken to. I believed in him as a character – he pitched it very nicely, reminding me of people I met when I was really and truly ‘infiltrating’ right-wing pubs in Thanet, as part of my research for a show about migration, during Farage’s election bid last year – an interesting coincidence. But I didn’t believe that he would accept my story and take me on board in his organisation so quickly. Not that I want to advocate that actors make audience members feel truly uncomfortable. But that edge could have been approached and played with, as it has been in previous Hydrocracker productions. I would also have liked more double-bluff along the way. Sometimes things felt a little too obvious and straightforward. Once I’d identified my target, she was exactly as the briefing had suggested, there were no hidden surprises in her story. I also felt I was ‘pulled out’ of the operation just as it was getting interesting.

Of course, I say all of this knowing how hard it is to get the balance right, especially in the opening weekend of a show with this many built-in complexities.

Operation Black Antler is an exciting and challenging new collaboration by two well-established Brighton companies with reputations for creating challenging off-site work. It draws on both their strengths – Blast Theory’s interest in work driven by an interaction with new technologies, placing the audience member at the heart of the action; Hydrocracker’s mission to create intensely political work in unusual spaces, using actors who interact with audience members. Deep swimming indeed… Dive in and you won’t be disappointed. Cower on the shore and you’ll never know the pleasures of swimming against the current.