A Nation’s Theatre Festival is showcasing an assortment of work from UK-based artists, with an eclectic programme at Battersea Arts Centre ranging from scratch pieces on a ‘pay what you can’ basis to full touring works.

A Nation’s Theatre Festival is showcasing an assortment of work from UK-based artists, with an eclectic programme at Battersea Arts Centre ranging from scratch pieces on a ‘pay what you can’ basis to full touring works.

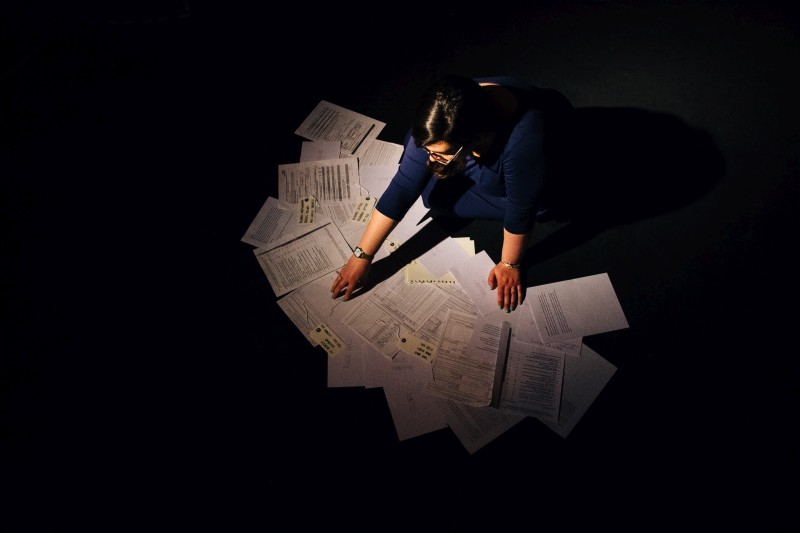

This Room by Kent-based artist Laura Jane Dean sits effectively within BAC’s architecture: a room in the old town hall theatre is stripped almost bare to reveal and pay homage to its own biography. This Room exposes the conversations, questions, decisions, and interactions that occur in a therapy room, usually confidential and unknown to the outside world. Supported by the Wellcome Trust, demystifying and raising awareness of mental health is a current and timely subject for theatre.

This solo piece is text based in the form of a personal lecture. It juxtaposes narratives written in formal language about medical conditions with the acting out of those conditions, the rational versus the emotional. Dean’s performance soon becomes more than a lecture, evolving into a lived experience of anxiety, obsessive compulsive disorder and how that feels. This is layered with a rational and philosophical questioning and understanding of what is happening both objectively and phenomenologically. The sophisticated awareness in the speech bridges the medical and emotional text. An intense hour unfolds with brief moments of lightness which could be extended to balance the heavy content.

Dean acknowledges the here and now as she smiles and greets us on arrival and takes the audience back and forth between relocating in time and geography to her therapy room and the existing room in BAC where we are referred to as the subject. There is a tension that underlies this piece, a fear or awareness that obsessive compulsive behaviours are pressing, urging, impulses that could manifest at any moment in all of us. These might be the ones described in the lecture, such as worrying that the house will burn down because the oven is left on, or Dean’s personal responses to her pairs of tights for, either repulsed by them or obsessed by thoughts of wringing her neck with them.

The design consists of a square space framed by lines of light along its boundaries, dressed with a table and boxes, a notice board, microphone and chair. The audience seating is arranged along three sides of this space, mirroring the boundary of the light. The space feels sparse and clinical like Dean’s succinct and matter of fact portrayal of her struggle. Eight forms pinned to a notice board and four storage boxes containing envelopes of reports and multiple pairs of tights make visual the notion of categorisation, of putting people into boxes, numbers into charts and charts into statistics, dehumanising the subject at each step. Dean takes the audience through the cognitive behavioural therapy she undertook to combat obsessive compulsive disorder. The space that becomes her therapy room gradually becomes our own as the fourth wall is repeatedly broken and we are encouraged to reflect on our own experiences.

A short interlude between each section sees Dean question the audience against a set of statistics in her hand. Statements about worries or urges are set against the percentage of women and men who experience them. As more men are said to imagine having sex in a public place than women, we giggle and glance at our neighbours to see if their hands are raised in admission as well. This brief promise of humour is starkly contrasted by two brave viewers raising their hand in admission to experiencing the urge to slit their wrists or throat when seeing a sharp knife. It is at this point that the walls of safety built up around us by humour are shattered in one fell swoop. It’s an intimate and frightening moment.

Dean subtly adjusts her text between conversation, narration, and something progressively rhythmic. Not quite a song but more than a monologue, the ‘I want to know things’ poem has an ebb and flow to the voice, a regularity in its repetition and a sense of knowing in its unanswered questions. This section describes what Dean is searching for, her thoughts and feelings while living through her OCD. Matched by a simple chase between suspended yellow bulbs and darkness and a light trickle of piano notes, the subtlety of the work is where it is at its most poignant and strong. Melanie Wilson’s soundscape sets up an interplay between Dean’s thoughts and her live speech which is key to communicating the barriers and tension that develop out of fear.

Timely voiceovers put into words the unsaid, the pressing questions of a once silent voice. This is the voice that Dean could not speak out loud at the time due to social expectations or fear; it is unedited and brutally honest. The repetition of ‘I’ and ‘you’ is exposing and confronting as the subjects of the speech swap between herself and her therapist and I can’t help but feel under the microscope from beginning until leaving the building. The repetition of ‘You are…’ for example, ‘You are petite, you are wearing clothes’, brings the very-absent therapist directly into this room.

Entirely relatable, the piece creates a thoughtful and contemplative space. Dean leaves us in her current state of ‘not knowing if I’m better or if I want to get better’. She doesn’t want it to be easy but it could be easier. We are all heavy, with the world on our shoulders. I have an impulsive need to hug her but she is gone. Maybe it is me who needs the hug.