Today’s instalment of the Treelogy, a trio of fast-paced and partially improvised shows on childhood stories featuring trees by young company Sleeping Trees, was a hilarious parody of Treasure Island. Versions of The Magic Faraway Tree and The Odyssey are also to be performed in a similar style, on different days. This production was nominated for a Total Theatre Emerging Artists’ Award in 2012 and the small studio in the Pleasance Below was electrified by the sheer energy and verbal dexterity of writer/performers James Dunnell-Smith, Joshua George Smith and John Woodburn reconstructing this well-known story with wit and panache.

Today’s instalment of the Treelogy, a trio of fast-paced and partially improvised shows on childhood stories featuring trees by young company Sleeping Trees, was a hilarious parody of Treasure Island. Versions of The Magic Faraway Tree and The Odyssey are also to be performed in a similar style, on different days. This production was nominated for a Total Theatre Emerging Artists’ Award in 2012 and the small studio in the Pleasance Below was electrified by the sheer energy and verbal dexterity of writer/performers James Dunnell-Smith, Joshua George Smith and John Woodburn reconstructing this well-known story with wit and panache.

Elements of improvised dialogue flourish within a well-structured narrative framework and although this production has been in existence for a number of years, it is clear that the actors are still having fun adding to certain sections as they go along. The cast’s comments on each other’s ad libs or sudden amusement at a new gesture or character embellishment kept the performance feeling fresh and immediate.

A real understanding of the novel’s characters, themes and subtext made for a lively production to which the audience responded strongly. The cast’s abilities included multi-roling (with the three performers playing everyone from Long John Silver to pirate crews and a group of rather intriguing Mermen!), effective physical techniques – clowning, slapstick and gestus – and the repeated use of key motifs whose shorthand aptly set scenes and showed transitions in time and place.

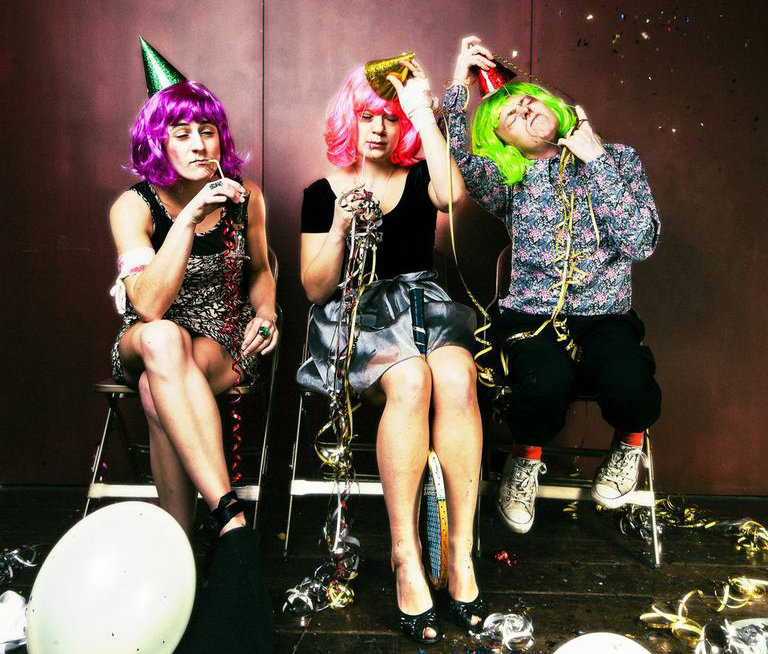

Use of melodramatic devices and exaggerated characterisation were combined exceptionally well with strong vocalised sound effects to further excellent comic effect, and the pace and energy of the piece built a real sense of momentum. Treelogy is an excellent example of improvised comic physical theatre done extremely well; a bare stage devoid of props or set, and a simply costumed cast, brought Robert Louis Stevenson’s world to life completely and brilliantly.